“The Day in Its Color”:

Charles and Jean Cushman

Eric Sandweiss

Journal of American History, 94 (June 2007) 132–42

Their names are Charles and Jean Cushman. The place is the Hotel Wofford in Miami Beach, Florida; the date, sometime in March 1939. The Cushmans have traveled here from Chicago, Illinois, in a maroon Ford Deluxe sedan, which they will soon drive north to visit her parents in their red-brick townhouse in Washington, D.C. We know the color of the car and the house, as we know the details of their itinerary, because of what he keeps beside him on the front seat as they drive: a new Contax IIA 35-mm camera, some canisters of Kodachrome color film, and a small spiral-bound notebook filled with handwritten annotations of every picture that he has shot.

From shortly before the time of this picture until 1969, this amateur photographer and sometime financial analyst, accompanied by his wife, drove roughly a half-million miles across the nation. He wore out three automobiles and produced fourteen thousand color transparencies along the way—pictures with no apparent intended audience beyond that small circle of friends and relatives whom one might dare invite to a Saturday-night home slide show. Among those pictures are a small number of portraits—including a very few, such as this one, for which the photographer used a tripod and timer to reveal himself to the camera.1

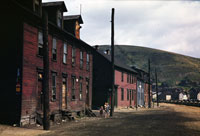

What caught my eye when I began looking at Charles Cushman’s slides three years ago was less the faces than the backdrop against which they appeared—a midcentury American landscape that I had long before resigned myself to knowing only in shades of gray. Cushman’s vivid images revealed a bygone world of Main Street stores, slum tenements, and farm fields that seemed, for a startling moment, as close and real as the street outside my window. Never mind the people, I thought; how should I make sense of this startling place around them?

View Larger Image

Eventually, though, these otherwise unremarkable portraits came to seem vital markers of an important journey. This was not just America, after all, it was the Cushmans’ America—and here were the Cushmans, encountered at various stages along a road that took them not only from coast to coast but from youth to old age. Framing the passages of their lives was evidence of a larger sort of passage—one that commenced in the concrete- and-iron landscape of extraction, production, and face-to-face trade that characterized early-twentieth-century America and petered out amid the ambiguous spatial order of a postindustrial age. Like a photograph exposed for maximal depth of field, the story of those juxtaposed personal and national journeys required a long gaze before both the subjects and their surrounding context came into focus.

My gaze first settled far from Miami Beach, on Posey County, Indiana. Writing later in his life, Charles recalled that he had been raised “pretty close to the soil,” and once you have been to his native Poseyville, you know that he meant the phrase as more than a figure of speech. Approaching from the northeast, you almost feel your car sinking into the shared floodplain of the two rivers—the Wabash, to the west, and the Ohio, to the south—that hold Posey County in their grip. It is there at the junction of the two rivers that Indiana tilts, like an off-kilter frying pan, to its lowest elevation. The county’s population peaked around the time of Cushman’s birth in 1896 and gently declined through most of the twentieth century.2

Today, the residents of places such as Posey County are apt to take a measure of pride in resisting the hazards of change. Their ancestors, however, had no intention of watching history pass them by. Charles Cushman’s southwestern Indiana, seemingly the remnant of a “simpler time,” as some would have it, was, by the time his ancestors arrived there in the 1830s, an integral part of a complex economic landscape linking sites of extraction, storage, processing, and trade in resources—a system that extended from remote places such as southern Indiana to port cities such as New Orleans, and thence across the world. Cushman would grow up to see—and to picture—that landscape as it matured and then collapsed beneath the weight of a new layer of economic, technological, and cultural imperatives that shaped the United States that we know today.

The coddled only child of small-town gentry, Charles Cushman left home to study at Indiana University in 1913. Like his near-contemporaries Hoagy Carmichael and Ernie Pyle, he arrived at Indiana University as a small-town Hoosier with big-time ambitions. He studied business and English while furthering his writing skills as “sporting editor” for the Indiana Daily Student. After graduation, an “unpoetic” stateside stint in the navy left Cushman in Chicago, and it was there that he established his professional skills—not as a photographer but as a traveler and firsthand observer of the economic processes that shaped the American landscape. His first sales position, with the Addressograph Corporation of Chicago, brought him into the ranks of a growing number of “commercial travelers,” who practiced an art similar to, but more sophisticated than, that of the nineteenth-century drummers whose lives were fictionalized by writers such as Theodore Dreiser and Meredith Willson. In 1922, Cushman began working as a research analyst for the La Salle Business Bulletin, a monthly market newsletter published by Chicago’s La Salle Extension University. In the years that followed, his work at the Business Bulletin added to his understanding of the inner workings of the American economy, and it further developed the “eye” that, in the coming decades, would make his photography of the American landscape distinctive.3

To read the Business Bulletin of the 1920s is to see the fulfillment—through economies of scale, improved communications, and mechanical innovation—of the promise of the economic culture pioneered by families such as the Cushmans, in places such as southern Indiana, one hundred years earlier. Information replaces uncertainty, writes the Business Bulletin’s chief correspondent, Archer Wall Douglas, in a typically upbeat passage, while “provincialism is fast vanishing under the educational influence and the wide mailing range of newspapers, the magazine, and the printed book . . . and the limitless scope of the radio.” Corporate-government cooperation, growing out of such successful World War I–era models as the U.S. Shipping Board and the U.S. Housing Corporation, helped reduce fluctuations in the credit cycle and limit the uncertainties of supply and demand. In much the same way as Rexford Tugwell (a Columbia University economics professor before heading Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Resettlement Administration) in his coauthored 1925 college text, American Economic Life and the Means of Its Improvement, the editors of the Business Bulletin developed a vocabulary in text and image for instructing a wide audience on the relationship of the economy to everyday life. As Constance Rourke, Edmund Wilson, Lewis Mumford, H. L. Mencken, and other critics would do for the cultural realm, social scientists such as Tugwell, Robert Lynd, Helen Lynd, and Robert Park sought to discern in the turmoil and variety of the American experience common threads from which to weave a coherent tapestry of post–World War I society. Whether focused on government, literature, or architecture, the cultural critics of the 1920s shared a commitment to making what Tugwell, describing his own work, called “a great generalizing effort to locate the germinal forces of the present”; to asserting the existence of a describable national character; to framing that character in terms of common ideals rather than of common blood; and to highlighting “the means of its improvement” for the good of the country. In a manner more specific to the task of economic forecasting, Cushman and his colleagues at the Business Bulletin took part in the same effort.4

View Larger Image

Broadly framed as the social science effort of the 1920s was, it depended for its authority on the growing accuracy of statistical collection and analysis. Standard Statistics, a financial research firm established in 1906, was the best known among the companies collecting and offering to sell such information directly to a growing clientele of individual speculators. In 1928, as opportunities for American investors continued to multiply without apparent limit, the company sought to broaden its customer base with a popular newsletter, Your Money. To edit the new publication, they brought to their New York City headquarters a young research analyst and editor with a knack for explaining economic data in terms that general readers could understand. His name was Charles Cushman.

Cushman was not alone in New York; with him had come his wife, the former Jean Hamilton. The two married on the first day of summer, 1924, in Chicago—the city where Jean had grown up and (earlier that month) graduated college. In her father, Joseph R. Hamilton, Cushman had already found not only the personal mentor he had lacked since the death of his own father but also a professional role model and, perhaps most important, a source of the financial support that would alter Charles’s subsequent career decisions.5

No one has written a biography of Joe Hamilton—at least not one that was called that. But we learn a great deal about his life from a thinly fictionalized book written much later, by his nephew. That nephew had been digging ditches in New York until Joe picked up the phone one evening and arranged for him to take a writing job with the New York American newspaper. The nephew was John Steinbeck; the book, East of Eden. Hamilton was the youngest of the nine children of the clan whose rise and fall in California’s Salinas Valley forms the dramatic arc of that book. As Steinbeck described him, the young Joe “daydreamed out his life”; unlike most of the family, he left the valley, “helping to invent a new profession called advertising,” where, as Steinbeck wrote with evident pleasure, his “very faults were virtues.”6 His experience as a nationally prominent copywriter, businessman, and innovator in visual media would influence others in the profession and eventually others in his own family—including both his son-in-law and his better-known nephew, each of whom would spend the next several decades creating personal pictures of the mark left by families such as the Hamiltons and the Cushmans on twentieth-century America.

In April 1929, just eight months after their move to New York, Jean and Charles returned to Chicago. Your Money lasted only until August, but Cushman continued with Standard Statistics as a field analyst in their Chicago office. By 1933, with Prohibition increasingly certain of repeal, Cushman received a boost from his father-in-law, who made the younger man secretary-treasurer of a new business venture, Drewrys Ltd., usa, a domestic offshoot of the Canadian brewery. Hamilton and the other officers sold the company in 1938, leaving them with what apparently was a substantial profit.7 Charles and Jean used some of their share to finance a driving trip to the West Coast; then, after returning home to Chicago, they headed south to Florida. It was during that run of personal good fortune that Cushman had opened the lens of his new Contax camera to the image of his and Jean’s smiling faces at the Hotel Wofford.

Cushman, a man of words, had experimented with images since at least 1918, but his introduction to serious camera work awaited the combination of his newfound leisure time and the availability of Kodachrome film, first marketed in 1936 but not available in pre-made cardboard slide mounts until 1938. Despite the work of chemists and amateur photographers (including one of Joe Hamilton’s brothers-in-law, as described in East of Eden) as far back as the mid-1800s, workable color technology awaited the patent in 1923 of the Eastman Kodak Company’s “subtractive” film process. The process used a threelayer emulsion that separated and then recombined the three primary color components of the light spectrum to produce images saturated in what the company shrewdly called “living color.” After its commercial debut, Kodachrome caught on with a growing group of “minicamers”—serious amateurs who enjoyed the fast lenses and light weight of the Leica and Contax cameras developed in Germany in the late 1920s.8

For all their potential influence on the photographic scene, color photographers remained a fringe group in the 1930s as far as the general public and the professional photography community were concerned. For Museum of Modern Art curator Beaumont Newhall, whose history of American photography first appeared in 1938, color work bore only passing mention as an amateur sideline to the serious photographic tradition whose history he both recognized and constructed in his own influential career. Newhall’s narrative privileged the socially critical (and almost entirely black-and-white) photographic tradition that then flourished, under the supervision of Roy Stryker, in the historical section of the Farm Security Administration’s (fsa) information division. The best of those pictures had already proved themselves, in Newhall estimation, “classic” in their timelessness. 9

Cushman never positioned his venture in relation to the projects of such professional image makers. His pictures lack both the overtly social or political purpose of Dorothea Lange’s photos and the formal rigor of Walker Evans’s, though he was likely aware of the many road-based documentary photography books appearing at the time and certainly aware of the work at the fsa. When Charles and Jean took off for California, her father, Joe Hamilton, headed in the opposite direction: to Washington, D.C., where he had been called to serve as director of information for an increasingly embattled Works Progress Administration (wpa). In defending Stryker’s group of photographers, the American Guide series, and the Federal Theatre Project, among other wpa ventures, from growing charges of political bias and bureaucratic bloat, Hamilton’s job was to articulate a relatively conservative justification for the federal government’s continuing support for the critical documentary tradition that had gathered steam in the 1920s and continued into the 1930s. He had to know how the tradition could interest people like himself and Charles Cushman, people like the readers of the La Salle Business Bulletin and Your Money; not just those who conceived it as a tool for social change.10

View Larger Image

After the initial trips of 1938–1939, Charles and Jean returned to Chicago. He bought a new twelve-cylinder Mercury Zephyr, and they soon hit the road again: south to New Orleans; west to Los Angeles; east to New York. Reconstructing in color images the economic geography lessons of the old La Salle Business Bulletin, he passed from Arizona copper mines to Louisiana cotton fields, from hydraulic power plants in the Northwest to chemical factories in Alabama. His itineraries often took him to unlikely sites that Stryker’s crew had photographed a few years previously. Was he aware of the correspondences? I think so. Were they part of a larger point? I think not. Absent the explicit rationale of Stryker’s famous “shooting scripts,” Cushman’s picture of America was defined more by “picturesque” sites and by his old business-analyst sensibilities than by the need to please, provoke, or educate a public audience.

Back home in Chicago, as the weather turned warm each spring, Cushman apparently left Jean to her own devices as he ventured out along the South Shore beaches, convincing good-looking young women in their bathing suits to pose for photographs that recalled the few shots he had made of his wife on that Florida vacation. The bathing-beauty images soon far outnumbered the Jean portraits, and Charles, now nearing fifty, grew bolder about entering the women’s names in his notebook: “Anni Sokal-discovered on Promontory P.-55th St.” or “Am. Airlines stewardess, Doris Irwin, takes sun.”11

In 1941 Hamilton stepped down from his post at the wpa, returning with his wife, Gussie, to their house in Hyde Park, Chicago. On January 3, 1943, a fatal heart attack cut short his retirement. The obituaries noted his long and prominent career in advertising and government service, mentioned his relation to Steinbeck, but said nothing of his impact as a creative muse, father figure, and financial benefactor to his son-in-law, the unknown itinerant photographer.12 Nor could they have predicted the impact of Hamilton’s death on his only child, Jean.

Two months later, on the night of March 19, Charles was working in his study on the third floor of the Hamilton house when Jean called him from below. Walking to the head of the stairs, he recalled, he heard her say “something about going away.” As he turned back toward his desk she followed him. “The next thing I heard two revolver shots,” Cushman later said. Both bullets hit him in the head. As he collapsed, Jean turned the gun on herself, firing a shot into her own mouth. Cushman managed to stagger to the home of his next-door neighbor, a physician, as Jean somehow called the police from a telephone on the second floor. By the time officers arrived, the doctor was administering first aid, and the family lawyer was already present to handle questions.13

“I am of an unhappy disposition,” Jean told officers that night at the Illinois Central Hospital, where both she and her husband lay recuperating from what turned out to be nonfatal wounds, “and thought it would be nice to die. I didn’t want to leave without him and I tried to kill him and myself.” Charles added that Jean’s father’s death had placed her under even greater emotional strain than normal. “All she had in mind was to kill me and herself,” he confirmed.14

Those events, which nearly ended their lives, marked the beginning of a long second act of Charles and Jean’s marriage. Jean left for Rogers Memorial Hospital Sanitarium in nearby Oconomowoc, Wisconsin. On Saturdays, Charles snapped her picture among the trees and flowers on the hospital grounds. Her portraits from that period reflect the emotional toll taken by the events, and they suggest the physical damage as well: the right side of her face appears stiff, if not paralyzed, and her right eye, which wanders from the apparent direction of her gaze, appears to be artificial.

In 1952, the couple left the scene of their mutual tragedy for good, settling in San Francisco. Week after week, the woman who had wanted to die and the man she had hoped to take with her sat, a camera’s width apart, in the front seat of the Mercury Zephyr. Most of their travels took place in the West. They vacationed in the Sierras and in the Southwest, photographing along the way. Closer to home, they explored the canyons and hillsides surrounding the old Hamilton ranch south of Salinas and wandered the back roads of Marin and Alameda counties.

It was beside one of those roads, in Niles Canyon—near the tracks that had carried the first transcontinental railroad to its western terminus in Oakland—that Charles stopped on a sunny day in February 1955 to take the picture of Jean shown here. Her drab coat sets off the brightness of her pink dress and her accessories from the deep greens and blues of a dewy East Bay winter morning. In a manner unlike her usual poses, Jean neither hides within the shadows of the car nor looks away from her husband; her gaze is as direct as ever it would be again. Gone are the traces of girlishness still evident on the beach seventeen years earlier; gone, too, it seems, is any remnant of the shame or shyness suggested by the photographs that followed the shooting and her hospitalization. “Take a good look,” her pose says. “This is who I am. And you”—staring at the man behind the range finder—“remember, you are all I’ve got.”15

On his wanderings through the streets of his new hometown, Cushman distanced himself, if only for brief periods, from that mindful gaze and from the marriage to which he clearly remained committed. Yet his mood on those jaunts appears not to have been melancholy. The city’s ample natural light, reflecting off low-rising pale stucco and frame facades, seems to have cheered him, even as it accommodated the limitations of his slow color film; the city’s high vantages such as Twin Peaks and Telegraph Hill allowed for plein-air views far above his usual myopic street-level perspective. From what we can tell, those were relatively happy years, at least for Charles. In the evenings he would sit by the living room bay window enjoying the sunset over the Golden Gate Bridge, sipping a cocktail, and listening to his opera records.16

View Larger Image

Charles took his last picture of Jean in the fall of 1968. Fittingly, she is half-obscured from view by their 1958 Ford Fairlane, which they are preparing to trade in at a Corte Madera, California, car lot. The following spring, a few months before her death, he would put away the camera altogether. In late 1970 Charles married fifty-three-year-old Elizabeth Gergely, whom he had met on one of his neighborhood walks. They remained together until his death—the result of a steadily worsening heart problem—two years later. When Elizabeth offered an interviewer her impressions of his earlier life—including details of Jean and her family—she neglected to mention that her husband’s first wife had once placed two bullets in his head. Charles and Jean, only children both, left no offspring. His only heirs, two elderly cousins in Posey County, died in 1978.17

What, then, remains of the lives of these two people who, instead of dying together, grew old together? And what of the nation through which they traveled? So far as we know, Cushman’s pictures remained in their boxes, seemingly destined never to be printed, never to be shown publicly. His will stipulated that the slides, with his camera equipment and related paperwork, be donated to Indiana University. They remained in boxes, known but unviewed, until 2000, when university archivists digitized all of the slides and mounted them in a searchable database, which debuted in 2003.18

Freed from the obscurity of the archives, Cushman’s collection reveals a picture of midcentury America that is quite different from others we have inherited in the historical record. His pictures lack the dispassionate distance typical of works by professional photographers concerned with converting their subject matter into formal or political statements. They also reveal few of the great changes touted by the form givers and policy setters of the time: the urban redevelopment, the federally subsidized highways and their nearby housing developments, and the massive rural public works projects. For all his loyalty to living color, it was a dying world that captured Cushman’s attention. Arriving at a once-distant future, the photographer and his partner looked around and saw little but the past—in the streets and fields behind them, as in one another’s faces. With little building taking place between the construction boom of the 1920s and the recovery of the late 1940s, the postwar United States represented a vastly underinvested landscape. By 1950, the United States’s refueled economic engines had moved the nation one step ahead of its stock repertory of cultural images (the family farm, Main Street, the billow- ing smokestacks, the tapered skyscrapers); the nation had come to seem a picture of itself. A landscape dominated by sites for extracting and processing natural resources, by small family-owned farms, and by concentrated urban neighborhoods, though still quite visible, had become a historical artifact. Viewed through pictures that are stripped of Newhall’s “classic” scrim of black and white, the persistence of that landscape seemed less a signifier of crisis, as many documentarians had portrayed it, than a reminder of the continued, tangible immediacy of the aging world that our business leaders, architects, and policy makers told us we had left behind.

Like an untold number of other Americans whose visual records lie as yet unappropriated by historians, Cushman saw the nation neither as an “average” snapshooter nor as a member of the ranks of self-described artists, academics, or social reformers. His sensibilities and experiences combined conservative and reformist instincts, complacency and dissatisfaction. Without rejecting his privileged position, he understood its limits. Without affecting the clothing or the life-style of the beat poet, the expressionist painter, the jazz musician, or even his cousin the novelist, he sought his own path to beauty and truth. Like another gray-flannel-clad artist of his time, the poet Wallace Stevens, who typed verse in stolen moments at his insurance office in Hartford, Cushman sought out “the day in its color.”19 He crafted an extraordinarily complete inner world from the fragments of life that he found around him, a world defined more in terms of his own experiences than in the service of an outwardly defined mission. The medium of color film, ceded by the professionals of his day to amateurs and advertisers, offered such a man a new tool for capturing the brief glow and the long, slow fade of the country he once knew and of the woman who saw it with him.

Eric Sandweiss is Carmony Associate Professor of History at Indiana University and editor of the Indiana Magazine of History.

Readers may reach Sandweiss at sesandw@indiana.edu.

1 For the photo of Charles and Jean Cushman at the Hotel Wofford, see Charles Cushman, “L-19= J and C on Wofford Beach,” March 1939, photograph, Cushman id 339.19, Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection, http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/cushman/results/detail.do?query=roll%3A3-39&page=1&pagesize=20&display=thumbcap&action=roll&pnum=P01590. Charles Cushman’s other slide images are also accessible online at Digital Library Program, Indiana University Archives, ibid., http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/cushman/index.jsp. Cushman’s photographs used in this article are available in their original color online at .

2 Charles W. Cushman to A. B. Keller, June 29, 1944, Genealogy File, Charles W. Cushman Collection (Indiana University Archives, Indiana University, Bloomington). On Cushman genealogy, see Cushman to Tom, Dec. 2, 1968, ibid. Posey County population data is available by a search in Fisher Library, University of Virginia, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center: Historical Census Browser, http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/collections/stats/histcensus/. In recent years, the county’s population slide has been reversed by exurban spread from nearby Evansville.

3 On Cushman’s childhood and college years, see Genealogy File, Cushman Collection; and Charles Cushman Scrapbook, ibid. On his navy experience, see “Information for the War Service Register of Alumni and Former Students,” ibid. On salesmanship during this period, see Walter A. Friedman, Birth of a Salesman: The Transformation of Selling in America (Cambridge, Mass., 2004). On La Salle Extension University, see “Baby Flats’ and Office Building Going Up,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1916, p. A6; “La Salle Extension Surplus Cut by Stock Dividends,” ibid., Feb. 19, 1926, p. 16; “Jesse G. Chapline, Noted Educator, Dies Suddenly,” ibid., July 3, 1937, p. 12; “Schools Offer New Opportunities,” Los Angeles Times, Jan. 25, 1931, p. C1.

4 La Salle Business Bulletin, 9 (Nov. 1925), 1. Rexford G. Tugwell, Thomas Munro, and Roy E. Stryker, American Economic Life and the Means of Its Improvement (New York, 1925), viii.

5 Cushman wedding announcement [1924], Genealogy File, Cushman Collection; Adolphe Roome IV telephone interview by Eric Sandweiss, Jan. 5, 2005, notes (in Eric Sandweiss’s possession); Elizabeth Gergely Cushman interview by Rich Remsberg, May 23 [c. 2001], notes, Genealogy File, Cushman Collection.

6 John Steinbeck, East of Eden (1952; New York, 2002), 41. Jackson J. Benson, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer: A Biography (New York, 1984), 91, 359–60.

7 On the chronology of Cushman’s employment history, see Application for Federal Employment, March 1, 1944, Genealogy File, Cushman Collection. On the Drewrys Ltd., usa, venture, see “Announce Plans for a $250,000 Brewery Here,” Chicago Tribune, Nov. 11, 1932, p. 12; “Predict Chicago Will Become Brewing Center of the United States,” ibid., Jan. 8, 1933, p. 18; Advertisement for Drewrys Ltd., usa, ibid., July 12, 1934, p. 14. Joseph R. Hamilton’s name does not appear in the available material on Drewrys; I have inferred his involvement from the presence on the Drewrys board of Cushman and the former Hamilton employee Theodore Rosenak.

8 For black-and-white photos taken by Cushman, mostly of family, neighbors, and vacations, dating back to 1918, see Photographic Print Files, Cushman Collection. Steinbeck, East of Eden, 43. On “minicamers” and the high price of the Contax camera and Kodachrome film, see “The U.S. Minicam Boom,” Fortune, Oct. 1936, pp. 124–29, 160–70. See also Laura Katzman, “The Politics of Media: Painting and Photography in the Art of Ben Shahn,” American Art, 7 (Winter 1993), 60–87.

9 Roy Stryker had been responsible for choosing the illustrations that went into Tugwell, Munro, and Stryker, American Economic Life and the Means of Its Improvement. Beaumont Newhall, Photography: A Short Critical History (New York, 1938), 72. See also Keith Henney, “Black and White,” Photo Technique, 1 (July 1939), 3; Steven W. Plattner, Roy Stryker, U.S.A., 1943–1950: The Standard Oil (New Jersey) Photography Project (Austin, 1983), 16, 18, 22; Bound for Glory: America in Color, 1939–43 (New York, 2004); and Andy Grundberg, “fsa Color Photography: A Forgotten Experiment,” Portfolio, 5 (July–Aug. 1983), 53–57.

10 For left-leaning photo-documentary books of the era, see, for example, Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White, Say, Is This the U.S.A. (New York, 1941); and Archibald MacLeish, Land of the Free (New York, 1938). On the ambiguity of Walker Evans’s political and artistic intentions for his photographs, see Douglas R. Nickel, “American Photographs Revisited,” American Art, 6 (Sept. 1992), 78–97; Alan Trachtenberg, “Walker Evans’s Message from the Interior: A Reading,” October, 11 (Winter 1979), 5–29; and John Tagg, “Melancholy Realism: Walker Evans’s Resistance to Meaning,” Narrative, 11 (Jan. 2003), 3–77. On the administrative and political crisis at the Works Progress Administration, see “Pinky over Aubrey,” Time, Jan. 2, 1939, p. 8; and “Colonel Harrington Lauds Bill to Women’s Press,” Washington Post, Feb. 1, 1939, p. 15. Hamilton’s work there is described in “Public Weighs Results of 9-Billion Expenditure,” ibid., March 24, 1940, p. B3.

11 Charles Cushman, “Sokal, Anni,” June 24, 1941, photograph, Cushman id 1041.8, Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection, http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/cushman/results/detail.do?query=1041.8&page=1&pagesize=20&display=thumbcap&action=search&pnum=P02336; Charles Cushman, “Doris Irwin of American Air Lines,” June 27, 1941, photograph, Cushman id 1041.16, ibid., http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/cushman/results/detail.do?query=1041.16&page=1&pagesize=20&display=thumbcap&action=search&pnum=P02344. See also Charles Cushman, “Light and Dark Meat. Promontory Visitors,” July 20, 1941, photograph, Cushman id 1241.10, ibid., http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/cushman/results/detail.do?query=1241.10&page=1&pagesize=20&display=thumbcap&action=search&pnum=P02360.

12 Cushman to Thomas Grant Hartung, Jan. 25, 1943, Genealogy File, Cushman Collection. “Joseph R. Hamilton,” Chicago Sun, Jan. 4, 1943, p. 13; “Joseph R. Hamilton,” New York Times, Jan. 4, 1943, p. 15; “Hold Funeral of J.R. Hamilton, Advertising Man,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 5, 1943, p. 17.

13 “Wife Turns Gun on Mate, Then Shoots Herself,” Chicago Tribune, March 20, 1943, p. 5; Chicago Sun, March 21, 1943, p. 10.

14 “Wife Turns Gun on Mate, Then Shoots Herself,” 5.

15 Charles Cushman, “Jean Near Niles,” Feb. 1955, photograph, Cushman id 0000.18, Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection, http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/cushman/results/detail.do?query=1955+AND+%28jean%29&page=1&pagesize=20&display=thumbcap&action=search&pnum=P04328.

16 Cushman interview.

17 Charles Cushman, “1958 Ford Fairlane Adieu,” Sept. 27, 1968, photograph, Cushman id 368.2, Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection, http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/cushman/results/detail.do?query=corte&page=1&pagesize=20&display=thumbcap&action=search&pnum=P15656. Cushman interview; Cushman to Edward Von Trees, Jan. 30, 1967, Indiana University Correspondence Files, Cushman Collection. Elizabeth Gergely died in 2003. Cushman’s cousins Anne Fullinwider (or Fullenwider) and Emma Fullinwider Barr died within a week of one another in Mt. Vernon, Indiana; see Barry Bolln and Pat Bolln, “Eighth Generation,” Fullenwider Family Genealogy, http://home.hawaii.rr.com/fullenwider/web/genealogy/pafg21.htm#711.

18 Cushman to Claude Rich, April 4, 1966, Indiana University Correspondence Files, Cushman Collection.

19 “It is never the thing but the version of the thing: / The fragrance of the woman not her self, / Her self in her manner not the solid block, / The day in its color not perpending time. . . .” Wallace Stevens, “The Pure Good of Theory,” in The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York, 1990), 329–32.