Markers indicate locations discussed in this article; click on a marker for more details about a location.

French Quarter

Bordered by the Mississippi River, Canal, Esplanade, and Rampart streets, the French Quarter is the original site of New Orleans. It is also known as the Vieux Carré, or the “Old Square.” More >

Lower Ninth Ward

Border by St. Bernard Parish, the Florida Canal, the Industrial Canal, and the Mississippi River, the Lower Ninth Ward is one of the last districts to be developed in New Orleans. More >

Tremé

Bordered by Rampart, Broad, and Canal Streets and Esplanade Avenue, Tremé is one of the oldest black districts in New Orleans. More >

Uptown/Downtown

In New Orleans Uptown and Downtown describe large sections of the city in respect to Canal Street and the Mississippi River, not individual neighborhoods. More >

The Disneyfication of New Orleans: The French Quarter as Facade in a Divided City

J. Mark Souther

Journal of American History, 94 (Dec. 2007), 804–811

The idea of a “Disneyfied” New Orleans is not new. Walt Disney, referring to the city’s Bourbon and Royal streets, once remarked, “Where else can you find iniquity and antiquity so close together?” Sharing the assessment of the local author Harnett Kane that the French Quarter, or Vieux Carré, “means New Orleans to the outside world,” Disney added New Orleans Square, a cleaner, shinier replica of the city’s most noted district, to his southern California theme park in 1966. New Orleans leaders, developers, and preservationists, meanwhile, were producing an urban space that, if not as controlled as its Disneyland counterpart, nevertheless invited comparisons.[1]

The identification of New Orleans with its original center largely explains why Americans were so disconcerted by the hidden city that floated to the surface in Hurricane Katrina’s wake. Beyond the famed French Quarter and the oak-canopied St. Charles Avenue streetcar line lay a deeply troubled community. New Orleans had long cultivated an alluring image by restoring distinctive architecture and promoting culture and revelry, so for many it came as a shock to see thousands of agonized and visibly poor African Americans huddled outside the city’s convention center and the Superdome after fleeing their submerged homes. Even longtime residents were taken aback by the scenes of suffering. Following Katrina, the journalist Adam Nossiter deftly captured the paradox of that selectivity: “You could live in a kind of dream-state in New Orleans, lulled into ignoring the crumbling houses you drove past, and their destitute inhabitants.” Katrina laid bare the persisting relevance of race and poverty that locals and tourists had long skirted.[2]

Why were locals and visitors able to shield themselves for so long from that unpleasant reality? Part of the answer lies in the development of New Orleans before the storm. The city’s failure to match the growth of other southern cities in the twentieth century effectively preserved much of its nineteenth-century appearance. A sense of stagnation discouraged an influx of newcomers who might have seen New Orleans as a place of economic opportunity, while it attracted those of a nostalgic or hedonistic bent, who became invested in holding onto reminders of the city’s past. And as New Orleanians embraced tourism, they reinforced, as the city’s focal point, the Vieux Carré, once the center of colonial Louisiana. Even the Quarter developed an erstwhile economic vitality not seen since the flush decades before the Civil War. In the meantime, the rest of the city suffered white flight, rising crime and unemployment rates, and shrinking municipal coffers.

The population of New Orleans grew more slowly than that in other major cities, dropping from twelfth to sixteenth place in the urban hierarchy between 1900 and 1950. Follow thread in Fussell, “Population History” >

In the twentieth century, many whites departed for New Orleans for outlying suburbs, helping disaggregate the city’s historically intermixed racial geography. Follow thread in Campanella, “Ethnic Geography” >

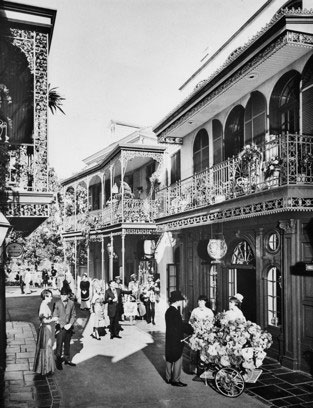

New Orleans Square, Walt Disney’s interpretation of the New Orleans French Quarter, opened at Disneyland in suburban Orange County, California, in 1966. Courtesy Cleveland State University, Cleveland Press Collection.

New Orleans Square, Walt Disney’s interpretation of the New Orleans French Quarter, opened at Disneyland in suburban Orange County, California, in 1966. The Disney attraction, a colorful but sanitized version of the Quarter, prompted public discussion of the merits of providing a similarly controlled experience for tourists in New Orleans. Courtesy Cleveland State University, Cleveland Press Collection.

For a time, a different economic trajectory seemed in the offing. World War II promised the possibility of New Orleans as a booming sun belt metropolis. As military bases, shipyards, and factories sprouted around the region, newcomers flocked to New Orleans, many settling in the newer sections of the city constructed on the flood-prone ground later ravaged by Katrina. Andrew Higgins, the head of the firm that built the amphibious craft used to invade Normandy, envisioned New Orleans as “the great metropolis of the future.” Less than a year after the war, New Orleanians swept deLesseps S. “Chep” Morrison into office as mayor. Morrison hoped to squelch New Orleans’s reputation for complacency, corruption, and vice summed up in its nickname “The City That Care Forgot.” His vision of a new New Orleans rested not on tourism but on capitalizing on the wartime stimulus and increasing port business. Unfortunately, the city’s poor management of manpower during the war and its preponderance of unskilled workers dissuaded industries from locating in the wishfully christened “Gateway to the Americas.” Additionally, its port lay on the cusp of a technological transformation in which labor-saving devices and containerization, coupled with increased competition from other cities, eliminated thousands of jobs. Thus, New Orleans lost its wartime momentum and gradually embraced its image as a pleasure capital.[3]

An important and enduring aspect of the city’s appeal to visitors was, until Hurricane Katrina, its reputation as a dimly lit, nonjudgmental world of sensual delights and sexual possibilities. In the nineteenth century, visitors used colorful phrases such as the “great southern Babylon” and “a perfect Sodom” to describe it. In more recent decades, journalists and visitors have called it everything from a “Vice Cesspool” to a “wild party heaven.” Throughout the twentieth century, otherwise upright Americans, though they might be reluctant to own up to it at home, flocked to the city precisely because of its reputation as an “exotic, erotic hot spot.” Follow thread in Long, “Race, Poverty, and Public Housing” >

Tourism moved toward center stage even as some business leaders muttered that what the Vieux Carré really needed was “a good fire.” Since the 1920s, preservationists had been forging a consensus favoring protection of the Quarter’s appearance. The preservation movement gathered the energies of a diverse set of people, including local professionals and socially prominent women, bohemians and tourists whose sojourns had become permanent, and the occasional heritage-minded social elite. Whatever their background, those cultural guardians wanted a neighborhood of restored residences and tasteful businesses, and they stood ready to resist any plans that compromised their own. Well before Katrina, privileged New Orleanians transformed New Orleans by concentrating national attention on a narrow swath of the city—away from those areas now effectively “redlined” (that is, the largely African American neighborhoods deemed unsafe investments) by revised flood maps. They also unwittingly primed the city to be eventually dominated by a tourism industry with a penchant for refashioning urban places in ways that mimicked the reassuring atmosphere of Disney’s “Happiest Place on Earth.” By the 1940s and 1950s preservationists and developers were at loggerheads over the proper uses for buildings and public spaces. While Bourbon Street’s emergence in those years as a neon-decked, risqué entertainment district alarmed the Quarter’s cultural stewards, later battles over commercial and highway encroachments into the district and municipal policies to concentrate tourism along the adjacent riverfront underscored that the Quarter was becoming a “Creole Disneyland.”[4]

Between World War II and Katrina, the contest to shape the French Quarter made the district critical to the city’s economic survival. The threat of redevelopment and highway projects, as well as growing efforts to balance the needs of locals and tourists, illustrate how the Vieux Carré increased its iconic value in a struggling city. The very different public discourse about Tremé, the mostly African American neighborhood across Rampart Street, underscores the Quarter’s favored status. The resulting transformation of New Orleans suggests much about how citizens and visitors valued different sections of the city. Most of New Orleans, like Tremé, became marginalized. A growing black population, which provided much of the culture, entertainment, and labor that supported tourism, lived in those areas. While it is inconceivable that a tourist trade catering chiefly to whites would have presented the often ugly realities of black urban life or that a tourism-focused transformation of the entire city would have been desirable, the privileging of the French Quarter ensured that local and visiting whites could “construct” a New Orleans relatively free of urban pathologies.

The growing centrality of the French Quarter shaped public debates over building architecturally evocative hotels and an elevated riverfront expressway along the Mississippi River. Those plans aroused preservationist outcry even as urban renewal and freeway projects went unopposed just blocks away in Tremé. In the 1940s few locals supported preservation, but by the 1960s the Quarter’s architecture shaped developers’ attempts to profit from the tourists it attracted. Notions of how the Vieux Carré should look drove efforts to demolish structures that did not match colonial- and antebellum-era styles favored by preservationists. Developers in the 1960s began to argue that new hotels dressed with lacy iron balconies and gas lamps reinforced rather than detracted from the Quarter’s tout ensemble, that static, romanticized notion of authentic cityscape.

One such hotel, the Bourbon Orleans, was scheduled to be built on the site of St. Mary’s Academy, a Catholic school for African American girls. After more than eighty years at that location, St. Mary’s was to be moved to Gentilly, a growing black section of the city (left in ruins by Katrina). Local lore erroneously connected the school’s ballroom with “quadroon balls,” where white planters and Afro-Creole women met in antebellum times. Preservationists recoiled at the developers’ plans to demolish the school to build a hotel. Parting company with many of her Uptown neighbors who embraced local myths but disdained the French Quarter, Martha Robinson, an elite reformer and preservationist, championed saving the convent, arguing that its ballroom was “the scene of some of the most glorious social events in the history of the city.” Robinson was, as the historian Pamela Tyler argues, a deeply committed civic activist, and yet she, a descendent of planters, also shared in the local inclination for summoning a romantic past to guide the modernization of New Orleans.[5]

Not surprisingly, African Americans, living during the civil rights struggle, saw the ballroom as a bitter reminder of slavery and felt little connection to an elite white conception of the French Quarter’s past. They had never felt welcome in a French Quarter trolled by white tourists, and they believed the hotel at least might provide more jobs for blacks. Perhaps they also sensed the irony in efforts to save a totem of white memory at the same time that a city-sponsored urban renewal project was claiming the homes of African Americans to build a “cultural center” around Congo Square, where slaves once gathered for recreation and sociability. The local black newspaper accused preservationists of “holding fast to the monuments of . . . antebellum southern traditions” and called for the building’s demolition. Ultimately, economic considerations prevailed, and the convent was razed. Tourists and newcomers who valued the Quarter’s bohemian flair began to question building similar hotels, which one northern transplant decried as “sugarcake imitations.” A moratorium on new Quarter hotels passed in 1969. The public debate about hotels suggests the preservationists’ success in persuading their fellow citizens that making the Quarter appear marooned in the past might pay dividends.[6]

The French Quarter had for years modernized incrementally without much resistance until historical associations became invested in its appearance and began to make any new construction seem the opening salvo in a modernizing offensive. Perhaps nothing demonstrated the preservationists’ aversion to change more palpably than their struggle against a project conceived during the Morrison administration. While tourism brought encroaching hotels, it also helped defeat a riverfront expressway designed by Robert Moses (an eminent New York urban planner who had designed freeways in a number of American cities), which, argues the historian Ari Kelman, would have severed the city from its river at historic Jackson Square. Aggressively touted by pro-growth downtown leaders, the expressway plan galvanized preservationists in the 1960s. To combat rosy predictions that the project would actually save the Quarter from traffic congestion, antiexpressway advocates invoked economic arguments of their own, contending that local businessmen had never appreciated the Quarter’s vital role in sustaining downtown merchants and tourism operators.[7]

Unable to sway expressway backers, preservationists mounted a national campaign that relied in part on the Quarter’s popularity with tourists, further reinforcing outsiders’ conflation of the old district with the city itself. In addition to a massive letter-writing campaign aimed at architects, preservationists, and politicians, expressway foes distributed flyers that urged tourists to protest the road, which would make New Orleans “look like any other town.” Preservationists also filed a lawsuit against the state highway department and the city government in 1967, arguing that the expressway would subject Quarter denizens to “a super-modern kaleidoscopic view . . . of varicolored vehicles by day and glaring headlights by night.” The President’s Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, meanwhile, determined that the road would damage the historic Quarter and recommended withholding federal funds.[8]

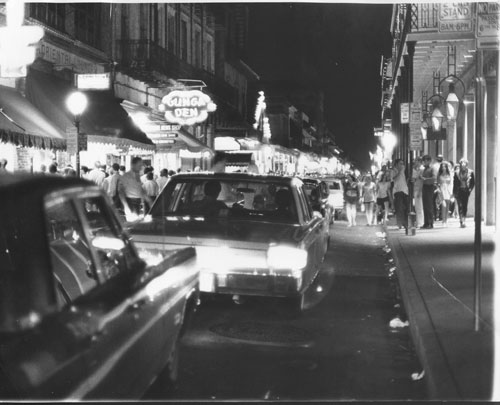

In this night scene of Bourbon Street in 1971, entertainment businesses such as the Gunga Den attract throngs of tourists. Courtesy New Orleans Public Library.

In this night scene of Bourbon Street in 1971, entertainment businesses such as the Gunga Den attract throngs of tourists. New Orleans’s most well-known street, Bourbon Street set the tone for a post–World War II transformation of the French Quarter into a tourist-oriented enclave on the fringe of downtown. Courtesy New Orleans Public Library.

Preservationist activism did not extend to Tremé, the neighborhood that furnished many of the jazz musicians who played in French Quarter establishments such as Preservation Hall. Divided internally and lacking political influence, African Americans were not yet in a position to spearhead their own successful preservation efforts. As a result, the federal government easily erected the elevated Interstate 10 through Tremé, felling rows of live oaks that once graced a vibrant boulevard in the black neighborhood. The freeway, along with a concurrent plan to build a cultural center touted as New Orleans’s version of New York’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, revealed that leading local whites had very different sensibilities about Tremé than they did about the French Quarter. Black heritage tourism, still fledgling in the 1960s and 1970s, did not interest local leaders attuned to transforming the Quarter into the city’s economic equivalent of a Disney theme park. Aside from intrepid tourists who ventured on foot to the shadowy St. Louis No. 1 Cemetery or sampled African American nightclubs, most whites heeded official cautions against straying across Rampart Street and the color line it symbolized. The French Quarter had no gates, but for local leaders its borders needed protection from the less predictable conditions beyond. Unlike Interstate 10, the cultural center never materialized, leaving local officials to scramble for an alternative plan. In the shadow of the expressway, remaining Tremé residents struggled to prevent the conversion of Congo Square (long ago renamed Beauregard Square after a Confederate general and, a century later, renamed again for the jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong) into an ersatz theme park patterned after Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, Denmark. Ultimately, no theme park was built, but the gated Armstrong Park acted as a barrier between Tremé and the Quarter.[9]

Cemetery Tombs. Photo by Alexander Allison. Courtesy Alexander Allison Photograph Collection, New Orleans Public Library.

Cemetery Tombs. Photo by Alexander Allison. Courtesy Alexander Allison Photograph Collection, New Orleans Public Library.

New Orleans’s thirty-one historic cemeteries chronicle the city’s history. The oldest cemetery, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, opened in 1789 following the great fire of 1788. The city replaced St. Peters cemetery (which no longer exists) as New Orleans’s designated burial site and began the tradition of above-ground burial. Before 1789, most of the city’s burials were below ground despite the marshy conditions and water filled plots. A growing sense of responsibility for the dead led the city’s wealthier families to begin building elaborate, above-ground tombs to protect the bodies of their loved ones. Mausoleums of all styles and sizes began filling New Orleans cemeteries. In the 1830s, several epidemics that swept through the area prompted the city council to pass burial ordinances restricting burial to existing above-ground structures, thus reinforcing the New Orleans tradition. Today, cemetery tours are popular with tourists, with much of the proceeds going toward cemetery preservation and restoration.

The hotel moratorium, expressway defeat, and creation of a buffer between black Tremé and its almost lily-white neighbor across Rampart demonstrated the success of preservationists’ pro-tourism rhetoric. Just five years earlier, Mary Morrison, a leading preservationist and sister-in-law of Chep Morrison, had rightly worried that preservationists, in their successful bid to persuade civic leaders of the value of a preserved French Quarter, had “saved the lamb and fatted it for the ultimate slaughter.” In the 1970s the French Quarter became more firmly entrenched as the center of a Disneyfied New Orleans. Mayor Maurice Edwin “Moon” Landrieu directed the renovation of the French Market into a festival marketplace, fashioned a flagstone-paved pedestrian mall from the streets bordering Jackson Square, and tried, unsuccessfully, to stage historical sound-and-light shows.[10]

The Disneyfication of the French Quarter encouraged large-scale development along the adjacent waterfront, now protected from a riverfront expressway. Although preservationists fumed that those projects would turn the Quarter into “a giant amusement park,” they were largely unable to stop or even shape their development.[11] The wharf-lined riverfront, which many Quarter residents had hoped might become a park following a proposed relocation of the port to eastern New Orleans, instead yielded to a string of tourist venues—Jax Brewery, Riverwalk Marketplace, Canal Place, Aquarium of the Americas, a Harrah’s casino, a Hilton hotel, and a nearly mile-long convention center—traversed by red streetcars.

The French Quarter and riverfront transformations also precipitated strident controversies over the management of tourism. While city hall rerouted Mardi Gras parades around the Vieux Carré, it proved unable to control the bacchanal that tourism attracted. Civic leaders could not repel the wave of youths who descended on the city during Carnival, squatting in Jackson Square and on the river levee. Quarter residents complained about unsavory, tourist-oriented businesses such as beer stands, peep shows, and massage parlors. As the Quarter’s population dwindled, street vendors, musicians, mimes, caricaturists, and fortune tellers clashed with resentful residents who remained to defend their neighborhood. Though one city councilman proposed an ordinance in 1987 to restrict new T-shirt, souvenir, and adult entertainment–oriented businesses, his effort failed. Tourism, in the eyes of many, had turned New Orleans into a ersatz caricature of itself in which, as one newspaperman lamented, the locals’ “main job will be to lend an air of authenticity to a city that once had it in spades.”[12]

Even before Katrina hit, New Orleans masked its troubles behind a facade of heritage and sensory pleasures in the French Quarter. In pursuing tourism, New Orleans leaders created a city that existed to parade itself to outsiders even as it endured dilapidation, crime, and population exodus. Landrieu’s successor, Mayor Ernest N. “Dutch” Morial, hoped to steer the city in a different direction by creating an industrial corridor in eastern New Orleans to diminish the city’s dependence on tourism, but he ended up being better known for hosting a world’s fair. When the oil industry collapsed in the mid-1980s, the New Orleans metropolitan area suffered a net loss of 65,000 people in five years.[13] Tourism leaders and city officials responded by increasing spending to promote tourism, expanding the city’s convention center, and fostering the conversion of many downtown office buildings into hotels. Predictably, the Quarter enjoyed extra police protection and expanded city services even as New Orleans’s municipal budget evaporated.

In the 1980s two primary engines of the local boom failed. The oil market went bust, which compounded problems associated with a long-term decline in the number of jobs at the port of New Orleans and left the metropolitan area in a depression from which it has never fully recovered. Almost at the same time, the federal pipeline to the cities almost shut down. Follow thread in Germany, “Racial Inequality and the Long Prelude to Katrina” >

It was little consolation for the nearly one-third of New Orleanians who lived in poverty (mostly African Americans) to learn that tourism was generating billions of dollars annually. Theirs was a New Orleans untouched by the colorful paint, neon signs, and bronze plaques that connote tourism. Until Katrina left behind a sodden, abandoned, urban wasteland they once called home, they were invisible to most Americans. The devastation left by the flooding has, to an extent, reordered tourists’ spatial understanding of New Orleans. Months after Katrina, tour buses groaned through eerily quiet streets as passengers gawked at the brown watermarks, blue tarps, and orange spray-painted rescue signs that now took their place alongside the more familiar iron balconies, gas lamps, and porticos. While disaster tours may do as much to sate voyeuristic appetites as heighten social awareness, a growing penchant for “voluntourism” promises to bring more than the expected social activists into contact with the city beyond the French Quarter. With the tide of Katrina coverage slowly receding, however, it is unclear whether that trend will pry most tourists from the much less unsettling experience of the Quarter.[14]

New Orleans is relying once again on tourism—the very economic development strategy that magnified the social disaster of Katrina—at a time when media images of violent crime and environmental ruin have diminished tourism’s potential boon to recovery. Yet city leaders continue to cultivate the French Quarter facade. They recently approved a height-limit waiver for a hotel tower to secure developers’ promise to prettify a “blighted” block of Royal Street.[15] Such continued attention to the tourist hub, along with discussion of a “reduced footprint” for the city, conveniently salvages the Disneyfied facade seen by tourists, while writing off the hidden areas where tourism’s laborers lived and its culture thrived. Indeed, Katrina’s flooding consumed the 80 percent of New Orleans that tourists rarely saw, including the notorious Lower Ninth Ward and part of Tremé. Perhaps the countless tourists, trying to make sense of a national tragedy in their own way by straying from the well-worn paths scripted by promoters, may compel New Orleans leaders to recast their city in ways that educate, enlighten, and encourage reform. If not, New Orleans, with its French Quarter ever at the forefront, may well recapture its pre-Katrina reputation as a “Creole Disneyland.”

Howard Jacobs, “Bourbon Street Held ‘Eden of Epidermis,’” New Orleans Times-Picayune, Aug. 21, 1973, sec. 1, p. 9; Bill Rushton, “Cityscape: Disneyland’s ‘New Orleans Square,’” New Orleans Vieux Carré Courier, Sept. 15, 1972, p. 14; “Thousands Sign Petition,” ibid., March 5, 1965, p. 2. On Disneyfication as a process of creating a standardized appearance and experience in American cities, see Sharon Zukin, Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World (Berkeley, 1991), 217–50.

[2] Adam Nossiter, “Awakening from the Dream That Was New Orleans,” Associated Press Online, Sept. 6, 2005, available at Lexis-Nexis Academic Universe.

[3] Raymond Moley, “Louisiana Renaissance,” Newsweek, Feb. 17, 1947, p. 108; Ken Hulsizer, “New Orleans in Wartime,” in Jazz Review: A Selection of Notes and Essays on Live and Recorded Jazz, Most of Which Were Written in the U.S.A. before the End of the War, ed. Max Jones and Albert J. McCarthy (London, 1945), 3–4; map in Eureka News Bulletin, 1 (Feb. 1942), 8, folder 65-1, Higgins Industries Collection (University of New Orleans Library, New Orleans, La.); “Journey in America: III,” New Republic, Nov. 27, 1944, p. 684; “The Great New Orleans ‘Steal,’” Fortune, Nov. 1948, p. 103; Charles D. Chamberlain, Victory at Home: Manpower and Race in the American South during World War II (Athens, Ga., 2003), 192–93; Arthur E. Carpenter, “Gateway to the Americas: New Orleans’s Quest for Latin American Trade, 1900–1970” (Ph.D. diss., Tulane University, 1987), 318, 326–37.

[4] Lou Wylie to Joseph Di Rosa, July 30, 1970, Steering Committee for the Vieux Carré folder, box 4, Moon Landrieu Papers (New Orleans Public Library, New Orleans, La.); Anthony J. Stanonis, Creating the Big Easy: New Orleans and the Emergence of Modern Tourism, 1918–1945 (Athens, Ga., 2006), 141–69; J. Mark Souther, New Orleans on Parade: Tourism and the Transformation of the Crescent City (Baton Rouge, 2006), 38–42; Peirce Lewis, “To Revive Urban Downtowns, Show Respect for the Spirit of the Place,” Smithsonian, 6 (Sept. 1975), 38. On a similar, though more native-born, elite-directed, preservation impulse in Charleston, South Carolina, see Stephanie E. Yuhl, A Golden Haze of Memory: The Making of Historic Charleston (Chapel Hill, 2005), 21–52.

[5] “Block Holy Family Sisters Again in Selling Property,” Louisiana Weekly, March 23, 1963, p. 1; Walter W. Gallas, “Neighborhood Preservation and Politics in New Orleans: Vieux Carré Property Owners, Residents and Associates, Inc., and City Government, 1938–1983” (M.A. thesis, University of New Orleans, 1996), 51, 54; Henry A. Kmen, Music in New Orleans: The Formative Years, 1791–1841 (Baton Rouge, 1966), 48–49; Monique Guillory, “Some Enchanted Evening on the Auction Block: The Cultural Legacy of the New Orleans Quadroon Balls” (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1999), 42–49; “Baffling ‘Issue’ re Ballroom,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 24, 1963, sec. 2, p. 6; Pamela Tyler, Silk Stockings and Ballot Boxes: Women and Politics in New Orleans, 1920–1963 (Athens, Ga., 1996), 83, 180, 182–83, 185.

[6] “Preserve Quadroon Ballroom for Whom?,” Louisiana Weekly, March 23, 1963, p. 11; M. J. Davidson to Clarence O. Dupuy Jr. [1966?], VCPOA-1966 folder, box S62-8, Victor H. Schiro Papers (New Orleans Public Library).

[7] Ari Kelman, A River and Its City: The Nature of Landscape in New Orleans (Berkeley, 2004), 209–10; “Names Sorted in Road Fight,” New Orleans Vieux Carré Courier, March 5, 1965, p. 2; George W. Healy Jr. to Martha Robinson, April 13, 1966, folder 17, box 7, Martha Gilmore Robinson Papers (Special Collections Division, Tulane University, New Orleans, La.); Mark P. Lowrey, “Our Past and Future,” New Orleans Vieux Carré Courier, Nov. 24, 1967, p. 4.

[8] Raymond A. Mohl, “Saving the Vieux Carré: Inside the New Orleans Freeway Revolt,” paper delivered at the biennial meeting of the Urban History Association, Milwaukee, Wis., Oct. 2004 (in Raymond A. Mohl’s possession), 8; “Ready to File Road Suit,” New Orleans Vieux Carré Courier, Feb. 3, 1967, p. 1; “Road Delay Two Years?,” ibid., Dec. 9, 1966, p. 1; “Ground-level OK: Council Vote Is 4 to 3,” ibid., Jan. 17, 1969, p. 1; Bill Bryan, “No Road: Volpe Transfers U.S. Funds to Outer Beltway,” ibid., July 4, 1969, p. 1. For letters from the preservationists’ campaign, see folders 22–27, box 7, Robinson Papers; Robinson to F. Edward Hebert, Jan. 16, 1967, folder 1, box 8, ibid.; Robinson to Russell P. Long, Jan. 20, 1967, ibid.; and Robinson to Claude F. Deemer, Jan. 20, 1967, ibid.

[9] Tad Jones, “‘Separate but Equal’: The Laws of Segregation and Their Effect on New Orleans Black Musicians, 1950–1964,” Living Blues, 77 (Dec. 1987), 27; Vernon Winslow interview by Jane D. Julian, April 12, 1972, typescript field note dated April 13, 1972, vertical file “Racism and Jazz” (William Ransom Hogan Archive of New Orleans Jazz, Tulane University); “Tavern Owners File Test Suit,” Pittsburgh Courier, Feb. 22, 1964, in Facts on Film, 1963–64 (microfilm, 4 reels, Southern Education Reporting Service, 1964), reel J4, frame 335; “Park to Honor Satchmo OK’d,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 26, 1973, sec. 1, p. 1; Emile Lafourcade, “Storm of Protests Brewing over Armstrong Park Plans,” ibid., Aug. 12, 1973, sec. 1, p. 42; Mrs. Emanuel Blessey and Alan Guma to Albert Saputo, June 8, 1973, vertical file “Armstrong Park” (Hogan Jazz Archive).

[10] Mary Morrison to Scott Wilson, Dec. 30, 1964, “Vieux Carré Property Owners and Associates–1964” folder, box S64-31, Schiro Papers; Charles Suhor, “The ‘French Quarters,’” New Orleans, 4 (Feb. 1970), 60; F. Monroe Labouisse Jr., “The Death of the Old French Market,” ibid., 9 (June 1975), 72–78; Robinson to Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Jan. 31, 1974, folder 5, box 21, Robinson Papers; Mary M. Morrison, “Square Improvements?,” New Orleans Vieux Carré Courier, Dec. 20–26, 1973, p. 12; “Lights Out,” ibid., Aug. 14–20, 1975, p. 2.

[11] Lowrey-Hess-Boudreaux, Architects, “Historic Riverfront as the Front Yard of the Vieux Carré, Prepared for Vieux Carré Property Owners, Residents, and Associates, Inc. (vcpora),” report, Oct. 10, 1990 (in J. Mark Souther’s possession).

[12] Lolis Eric Elie, “Our Town Is Being Invaded,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 23, 2001, p. B1; Tom Bethell, “The Street People: Why They Come to Mardi Gras,” New Orleans Vieux Carré Courier, March 2, 1973, p. 1; “103 Arrested in Crackdown on Hippie Herd,” New Orleans States-Item, Feb. 9, 1970, p. 5; Coleman Warner, “Panel Backs City Permits for Quarter,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, Dec. 16, 1987, p. B3; Frank Donze, “Bourbon Street T-shirt Ban Defeated Again,” ibid., Dec. 9, 1988, p. B3.

[13] Monte Piliawsky, “The Impact of Black Mayors on the Black Community: The Case of New Orleans’ Ernest Morial,” in The African American Experience in Louisiana, ed. Charles Vincent (4 vols., Lafayette, 1999–2002), C, 533; Vincent Lee, “Tourism No Cure for N.O.—Morial,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, Jan. 18, 1978, sec. 1, p. 2; Mickey Lauria and Vern Baxter, “Residential Mortgage Foreclosure and Racial Transition in New Orleans,” Urban Affairs Review, 34 (July 1999), 766–67.

[14] Christopher Cooper, “Disaster Tours Pass Ninth Ward and Fats Domino’s House,” Wall Street Journal, Dec. 27, 2005, p. A1; Steve Hendrix, “Is New Orleans Ready for Tourists?,” Washington Post, Jan. 29, 2006, p. P1; Jaquetta White, “Work and Play; More Tourists Want to Do a Good Deed While They’re Having Good Time—A Trend That New Orleans’ Wounded Industry Would Love to Latch Onto,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, Jan. 28, 2007, p. C1.

[15] Bruce Eggler, “Council OKs Hotel Tower,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, Feb. 16, 2007, p. B1.