Resources

New Orleans Jazz

Early, 1890s–1920s

Often regarded as a predecessor of jazz, ragtime was at the height of its popularity in the late 1890s to the early 1920s. Descendant from dance forms, ragtime is characterized by its “ragged,” syncopated (offbeat) rhythms. New Orleans bands, such as Buddy Bolden’s (1877–1931), began to play a looser, slightly more improvisational style of ragtime. Though similar in style to ragtime, this music was played by ear, not from sheet music, and was based on practice sessions and memorization. In addition to Bolden, other key figures in the early New Orleans jazz style included the clarinetist “Big Eye” Louis Nelson Delisle (1880/85–1949), the drummer Papa Jack Laine (1873–1966, the white leader of the Reliance Brass Band), and the cornetist Freddie Keppard (1890–1933).

Musically, players shared the melodic line, emphasizing ensemble playing rather than the improvisational solos for which jazz is now known. By the early 1920s, however, the cornetist often performed the main melody. Early recordings present a relaxed playing style, slightly off the beat, at a somewhat slower tempo, as hallmarks of New Orleans jazz. A smaller band size (about 5–7 musicians) also typifies the style.

Early New Orleans jazz bands combined the instruments of black brass bands with that of string bands; (the former usually performed at social and religious events and the latter at dances and parties). The first cornet “king” was Buddy Bolden, and his incorporation of blues and ornamentation of existing melodies marked a departure from the predominant ragtime style. His extraordinary playing style and personality also created a competitive tradition among early jazz bands, particularly among cornet players, and musical duels among jazz bands were “fought” on the city’s streets. Louis Armstrong (1901–1971), one of the most famous of New Orleans musicians, was crowned a cornet “king.” Armstrong’s mentor, Joe Oliver (1885–1938), was referred to as “king” in Chicago, but was not officially a “king” until 1949 when he became King Zulu; his “crowning,” however, was temporary, lasting only through Carnival.

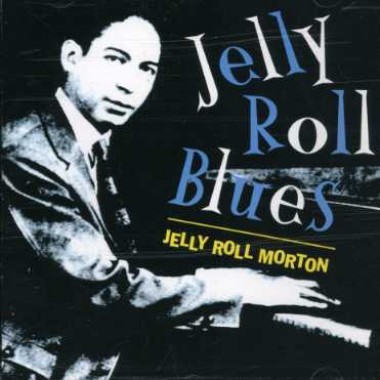

Like Bolden, the jazz pioneer Jelly Roll Morton (1890–1941), got his start performing in the notorious Storyville district. The self-proclaimed inventor of jazz, Morton was regarded as one of the best pianists in Storyville. After 1907, he began to tour in minstrel shows throughout the South and, by 1915, began publishing his jazz compositions with the tune “Jelly Roll Blues” [cover image]. In 1926, he signed a contract with Victor. Morton’s prestige rests on the way he polished the idiom as a composer and arranger.

Classic, 1920s

Many consider the 1920s the height of New Orleans–style jazz, “when the music was widely recorded, and figures such as Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, and King Oliver developed the music to an art form of shape, variety, definition, and possibility.”

As New Orleans musicians performed in cities around the United States and abroad, the popularity of jazz exploded. Some musicians left the city, moving to Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco—including the Original Dixieland Jazz [Jass] Band, Joe “King” Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, New Orleans Rhythm Kings, Kid Ory, and Sidney Bechet. Many, however, stayed—Sam Morgan, Jones and Collins Astoria Hot Eight, Papa Celestin, Halfway House Orchestra, and the New Orleans Owls, among them. This immigration lead to a proliferation of jazz styles and variegation within the New Orleans tradition. The key to understanding the similarities and differences is the respective environments and the common desire of New Orleans jazz musicians to always satisfy audiences, no matter where they might be. To accomplish this goal, they adapted musically to their new environments and audience expectations. (A modern parallel is the two markets that exist in New Orleans: tourism and community.)

The popularity of New Orleans–style jazz declined in the early 1930s, as audiences gravitated to the new swing style. A departure from early jazz, swing was based on larger ensembles whose interaction was guided by arrangers, rather than the free-flowing harmonizing and collective improvisation associated with New Orleans style.

Revival/Traditional, 1940s–50s

In the late 1930s, the appearance of jazz histories such as American Jazz Music, by Wilder Hobson (New York, 1939), and Jazzmen, edited by Frederic Ramsey Jr. and Charles Edward Smith (New York,1939), revived an interest in New Orleans jazz and created a market for earlier, traditional jazz recordings—such as those of Oliver, Morton, and Armstrong. This resurgence sparked a movement to resurrect the New Orleans style; some musicians wanted to re-create this music, while others attempted to adapt old music to the newer swing style. This movement revived the careers of many New Orleans musicians such as Bunk Johnson, Kid Ory, Sidney Bechet and George Lewis.

A Note on Dixieland

The Traditional (cited as authentic jazz) and Dixieland (considered imitation) dichotomy is largely a construction of 1930s jazz critics. Some New Orleans musicians (white and black) used the terms interchangeably, particularly around the period 1917–1927. Making an absolute distinction can thus be problematic historically.

Discography

- Breaking Out of New Orleans, 1922–1929 (4 CDs). JSP921. 2004: UK.

- The Atlantic New Orleans Jazz Sessions (4 CDs). Mosaic MD4-179.1998: USA.

- The Complete Original Dixieland Jazz Band, 1917–1936 (2 CDs). RCA 66608.2 . 1995: USA.

- Jelly Roll Morton, 1926–1930 (5 CDs). JSP 903. 2000: UK.

- Louis Armstrong, The Hot Fives and Sevens (4 CDs). JSP100. 1999: UK.

- New Orleans: Great Original Performances 1918–1934 (CD). Louisiana Red Hot 613.1998: USA.

Listening online

WWOZ 90.7 FM New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Station. http://www.wwoz.org/

Further Reading

Online

Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_New_Orleans

In Print

- The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, (2 vols., New York, 1988). General overview.

- Donald M. Marquis, In Search of Buddy Bolden: First Man of Jazz (Baton Rouge, 1978). Provides many insights into the turn-of-the-century New Orleans music scene.

Special thanks to Bruce Raeburn for his assistance in preparing this overview.