Day 2: Terrorism on American Soil?

Exercise 1

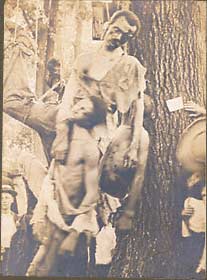

Photograph of a 1906 lynching in Salisbury, North Carolina

Essay by Claude A. Clegg III

The 1906 Salisbury Lynching

The 1906 Salisbury Lynching

by Claude A. Clegg III

On August 6, 1906, three African American men—Nease Gillespie, John Gillespie, and Jack Dillingham—were lynched in Salisbury, North Carolina. These mob murders were ostensibly precipitated by the axe murder a month earlier of a local white family for whom the men had worked. Following the abduction of the men from the local jail and their midnight hanging before an audience that some estimated to be in the thousands, one of the lynchers was arrested and prosecuted for his role in the mob executions. Given the rare nature of such a trial, the courtroom action was full of drama, anticipation, and anxiety as the case went all the way to the North Carolina Supreme Court. Ultimately, the high court upheld the fifteen-year sentence of George Hall for conspiring to murder Nease Gillespie, John Gillespie, and Jack Dillingham. This conviction of a lyncher was the first in North Carolina history and one of the earliest in American history. However, in only prosecuting Hall for this communal breach of the law, the symbolism of the punishment conveyed mixed meanings. It simultaneously signaled that lynchings were becoming unacceptable expressions of extralegal retribution and confirmed that local and state authorities were limited in their willingness to pursue lynch mobs.

Within the context of its times, the prosecution of George Hall highlighted a confluence of political and cultural trends that had characterized southern history since emancipation. Lynching as a social phenomenon had largely evolved into a white-on-black crime, a stark method of dramatizing the racial boundaries that protected white privilege and domination from black encroachment. Mob murders of African Americans for various alleged offenses—especially murder or rape—were as much aimed at terrorizing black communities into silence and deference to white supremacy as they were about lethally penalizing individual blacks for putative transgressions against (white) communal norms. In conjunction with codified segregation, disfranchisement, and other assaults on black liberty and citizenship, lynching consolidated the power of white reactionary forces. Aspiring politicians, yellow journalists, and domineering employers tolerated and even cultivated a climate of mob violence in North Carolina and elsewhere, confident that federal officials would not find it politically expedient to come to the defense of African Americans who were being removed en masse from voter rolls. Importantly, the practice of lynching appealed to the worst biases and fears of white voters and workers, who were often anxious about their own place in a social order facing the vagaries of modernity.

If the 1906 Salisbury lynching was a microcosm of the forces of race, class, and history that had influenced the larger American experience, then its aftermath pointed, hopefully and cautiously, to new possibilities regarding North Carolina race relations. The conviction of Hall did, in fact, coincide with a lull in lynchings in the state. By the end of World War I and the advent of the Great Migration, North Carolina governors, ever-conscious of the state’s image as a harbinger of the “New South,” were in correspondence with the recently formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which had taken a strong public stance against mob murder. While lynching would not disappear completely from North Carolina prior to World War II, the number of incidents diminished greatly over the four decades following the Salisbury murders.

Claude A. Clegg III is professor of history at Indiana University. Among his publications is Troubled Ground: A Tale of Murder, Lynching, and Reckoning in the New South (2010), which focuses on a 1906 lynching in Salisbury, North Carolina.