Day 2: Terrorism on American Soil?

Exercise 1

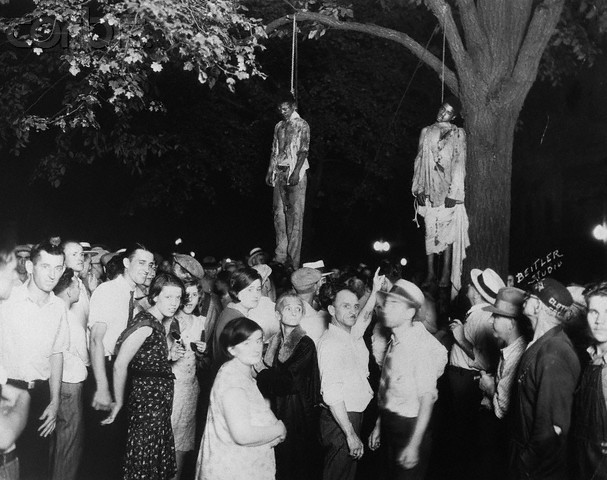

Photograph of a 1930 lynching in Marion, Indiana

Essay by James H. Madison

A Lynching in the Heartland: Marion, Indiana, August 7, 1930

A Lynching in the Heartland: Marion, Indiana, August 7, 1930

by James H. Madison

On a hot August night in 1930 a crowd gathered in front of an Indiana jail—men, women, and children shouting and jeering, demanding that the sheriff release his three prisoners. Three African American teenagers—Tom Shipp, Abe Smith, and James Cameron—huddled inside their cells, charged with the murder of a white man and the rape of white woman. Some among the thousands of people in front of the jail formed a mob. They beat down the jail doors, pulled the three youths from their cells, brutally beat them, and dragged them to a tree on the courthouse square. At the last minute the mob spared Cameron, the youngest and most boyish of the trio. Smith and Shipp died, lynch ropes around their necks, their bodies hanging as the town photographer captured one of the most famous lynching photographs in American history.

This Marion, Indiana, lynching is among several thousand in American history, though unlike most it happened in the North and in a community with little harsh racial antagonism. It also happened “late,” decades after the heyday of late nineteenth-century vigilante violence. Yet the Marion tragedy, like many southern lynchings, was a spectacle lynching. The mob was not content to murder their victims at the jail or to carry them off to an isolated spot. They chose the courthouse square because it was the civic and geographical center of town. The mob deliberately performed their drama on that stage, using lynch ropes as their central props. They insisted the county coroner not immediately cut down the two bodies. They must hang through the night, they shouted, to send a message to blacks who stepped out of line. Long after the sheriff finally cut the lynch ropes, the photograph remained: the upper half with its vivid brutality; the lower half showing ordinary Americans without sorrow or shame.

Some in Marion and elsewhere challenged this extralegal violence. Flossie Bailey, the head of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), immediately sent demands for justice to local and state authorities and called personally on the governor. She also contacted Walter White, the head of the national NAACP. White travelled to Marion from his New York office to conduct his own investigation. He identified mob leaders and issued his report. The NAACP’s magazine, the Crisis, ran the brutal photograph as part of the organization’s long campaign against lynching. So did some African American newspapers. Many whites expressed regret but failed to act. The exception was the Indiana attorney general, James Ogden, who initiated his own investigation. Most local authorities resisted, and all claimed they could not identify mob leaders.

Outside pressures for justice, particularly from Ogden and White, eventually caused the trial of two accused mob leaders, but each was quickly found innocent by juries of twelve white men. No one was ever punished for the murder of Tom Shipp and Abe Smith. A small victory came when Flossie Bailey successfully pressured the Indiana state legislature to pass a stricter antilynching law in 1931. Bailey and others also used the Indiana tragedy to argue for federal legislation, supported even by the Marion newspaper, but that movement failed.

The photograph and the memories remained. As late as the civil rights struggles of the 1950s some whites in Marion reminded African Americans of what would happened if they violated white norms. Increasingly, however, the memories turned to shame, sometimes suppressed in a willful forgetting, sometimes pulled out to encourage the necessity of justice for all.

No one forgot, certainly not black Americans. Sarah Weaver Pate, a teenager in 1930, told an interviewer in 1994 that “we’re like the rabbit now; we don’t trust the sound of a stick.”[1] James Cameron, the sixteen year-old who survived the lynching, never forgot. He titled his autobiography Time of Terror.[2] He devoted the last decades of his life to telling the story, always in contexts of justice and American ideals. More Americans came to understand that lynching was not a sidebar but a central feature of American history.

James H. Madison is the Thomas and Kathryn Miller Professor of History at Indiana University. Among his publications is A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America (2001), which focuses on a 1930 lynching in Marion, Indiana.

[1] James H. Madison, A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America (New York, 2001), 143.

[2] James Cameron, A Time of Terror (Milwaukee, 1980).