|

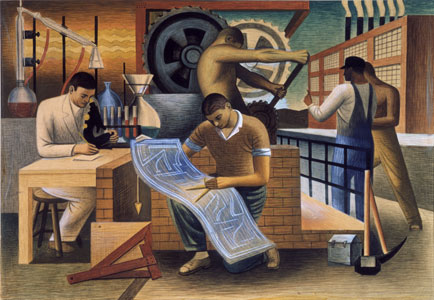

Thinking Visually as Historians: Incorporating Visual Methods David Jaffee When students encounter images, they often offer incomplete readings, demonstrating difficulty integrating their insightful visual readings with contextual historical understanding. When asked to "look" and "react" to images, they frame responses that open and close with immediate reactions. All too often, visual materials promote relatively simplistic emotional interpretations because the student viewers offer freestanding responses based solely on the image before them, unencumbered by the context or additional documentation historians use to make meaning with such powerful visual documents. Studying the way my students looked at visual materials, I realized that word and image needed to be reunited if students were to learn to think visually as historians. I came to this conclusion by taking the pedagogical turn: watching my students look, paying attention to the intermediate steps they took on their way to understanding historical problems and mastering the use of sources. Analyzing their work in the light of the scholarship of teaching and learning has helped me develop a strategy that pushes students to see historical context, connection, and complexity as they develop interpretative strategies for visual sources. For several years, I have collected evidence of student learning as a result of doing the online viewing assignments in my urban culture course, Power, Race, and Culture in the U.S. City, taught at the City College of New York. From the start, students were eager to look at the images as well as the historical and literary texts I posted for them. But the exercise of putting them together, of moving back and forth as a historian might do, proved elusive for many. When they moved onto the terrain of images, many students offered suggestive readings of the individual images before them, and they even referred to other visual materials, but few could integrate multiple sources into an interpretative narrative. I saw evidence of this difficulty when I asked my students to look at the 1941 murals at the Health and Human Services Building, created by Seymour Fogel, and to describe and interpret what they saw. Henry wrote:

David Jaffee uses Seymour Fogel’s Industrial Life (1941) in an image-viewing assignment for his course Power, Race, and Culture in the U.S. City at the City College of New York. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the General Services Administration. Most students followed Henry, with general comments about the industrial character of the objects, drawn from the murals√≠ titles, for example, and from the figures. They referred to the image√≠s visual qualities or its historical significance but were unable to weave the parts into a larger whole. A few students expressed more complicated understandings of the images as visual constructions. Olivia perceived that portrayal of industrial work in a "romanticized light" as a historical change from earlier representations. Arthur, commenting on another of the murals, pointed out their idealized nature, connecting them to other New Deal and World War II√Īera art, including the paintings of Norman Rockwell and the photographs of Dorothea Lange, both discussed in earlier classes. He could relate the medium of the mural as well as the significance of Fogel√≠s style of drawing (which he likened to "a way that marble might be sculpted into statues") to the murals√≠ message, their "monumental" representation of the force of family life.12 Yet, like most other students, Arthur did not raise relevant questions of patronage and audience or muse about the historical "purpose" of the mural project.13 Henry did attend to placement, but his visual analysis was slim and unconnected to his thematic framework. Even when Olivia and Arthur offered sophisticated understandings of the images, they did not connect their visual readings to text-based course materials√≥primary and secondary. Even the best students that first year offered separate, unintegrated readings of texts√≥visual and literary. Analyzing their efforts, I realized that students needed more scaffolding so that they could learn to move between historical, literary, and visual materials. Perhaps, I thought, I could create an online miniarchive, selecting sources that could enrich the complexity of their readings while helping them keep the context in sight. I wanted their experience in the miniarchive to model how scholars revisit their assumptions in a recursive process of intertextuality, repeatedly moving back and forth among texts and other sources as they weave them together. My new assignment asked students to look at two 1837 portraits of Indian leaders: Wijňôn- jon, Pigeon√≠s Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington by George Catlin and Keokuk: Chief of the Sacs by Charles Bird King.14 Each then wrote "a paragraph or two explaining what you see," a provisional interpretation the student shared with a partner before moving into a miniarchive containing documents selected to help the students situate the two representations: more portraits; speeches by Keokuk; text from Thomas Loraine McKenney√≠s History of the Indian Tribes of North America, where the Keokuk portrait appeared; writings by George Catlin about Pigeon√≠s Egg Head; and two extensive Web sites. From this miniarchive, students selected two documents that they thought added context and meaning to their initial reaction to the portraits.

At the City College of New York, David Jaffee asks students to use a miniarchive of documents to assist them in interpreting George Catlin’s Wi-jún-jon, Pigeon’s Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington (1837–1839). Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison Jr. Students encountering George Catlin√≠s 1837√Ī1839 portrait of Pigeon√≠s Egg Head often flatten their readings to fit into what they initially understand as the starkly contrasting choices of accommodation or resistance, sellout or revolt, facing Native American leaders in the early nineteenth century. The visual and textual materials of the miniarchive prodded students to move beyond those dichotomies, developing their historical reasoning and realizing more complex understandings. Using these additional sources to inform her reading of the Catlin portrait, Isadora imaginatively reconstructed the Assiniboines√≠ response to their leader√≠s foolish exchange of his "impressive Indian accoutrements" for foppish attire, including his high-heeled boots, fan, and umbrella, and the liquor bottle in his back pocket, interpreting his actions as compromise in the face of overbearing force. When Isadora turned to the Keokuk portrait, she continued to wrestle with the ambiguity of the image: When looking at this painting of Keokuk, one feels that there is something different about this majestic Indian chief. The feathers and animals√≠ skins indicate that he is a powerful, typical Indian chief. . . . But what makes this Indian chief sort of ambiguous? Why does he convey both Indian pride and strength and the acceptance of whites√≠ values?Additional sources, McKenney√≠s History of the Indian Tribes of North America and information on the interpretative stance of the painter Charles Bird King, helped her contextualize the portrait: In fact, Keokuk refused to collaborate with another Sac chief (Black Hawk) to fight against the whites, who were going to take their lands. He accepted to exile with his followers and was therefore much respected by the American government. He succeeded in constantly convincing his people not to join the war because he knew√≥according to Thomas McKenney, who was commissioner of Indian affairs between 1824 and 1830√≥that they would be defeated. He is generally depicted as a strong, determined and very tactic person. And [King] clearly depicts this sort of dichotomy that characterizes Keokuk: he was both a typical Indian chief who, with calm and realism, governed and protected his people and a good negotiator who knew how to deal with the whites. That is why he still appears as a majestic, respected chief on the painting, unless the painter, as it was often said about him and his passion for the Indians, idealized the character and improved the reality of the time.Moving beyond conventional accounts that frame Native American choices as either accommodation or resistance, Isadora had begun to tell a far more complex and messy historical story of a leader who had to wend his way through competing native factions and a welter of governmental officials, local and national, as well as deal with the divergent demands of settlers and reformers. She also understood that the sources√≥both texts and visuals√≥were not unmediated; the Native American voice√≥and body√≥comes down to us through Anglo hands and transcriptions. Yet, looking at the portraits by Catlin and King, she had seen some of the layers of complexities that allowed their subjects to represent themselves through pose and costume rather than merely to be represented by the painter. Like John Singleton Copley√≠s wealthy merchant subjects, Catlin√≠s Pigeon√≠s Egg Head and King√≠s Keokuk collaborated in constructing their likenesses. Isadora demonstrated how students can learn to read portraits in their historical context, appreciating complexity.15 Like most students, Isadora had plunged into the miniarchive to select specific texts directly relating to the portraits. Her classmate Judy used the miniarchive differently. She chose sources seemingly distant from the original portraits: an appeal by the Cherokee chief John Ross protesting Indian removal in the 1830s and the exoticized depiction of vanquished Indian leaders on the cover of an early twentieth-century popular periodical. These she deployed to explore the broader topic of the perils of assimilation. Here, she modeled the practice of an expert or professional historian who enters an archive with a series of questions or a tentative hypothesis in search of evidence, pulling apparently unconnected texts into a relationship and then constructing a plausible story. By yoking portraits and prose together, this exercise moved beyond the mere addition of images as illustrations, instead helping students think visually as historians. In creating the miniarchive, I wanted to push students away from freestanding looking and toward historically contextualized seeing of the visual evidence. Watching Isadora and other students move from examining a single image to comparing two images and then to contextualizing particular portraits within a miniarchive of word and image, I learned how students gain an understanding of the complex strategies that Indian leaders devised in the early nineteenth century. Students discovered for themselves the coexistence of choice and constraint. They came to appreciate how the power and pressure of the new American state limited Pigeon√≠s Egg Head and Keokuk but how the two leaders nonetheless deployed imaginative strategies to navigate the new political world that they faced. Like their subjects, historians too face constraints√≥the use of evidence, modes of documentary analysis, the need to connect the local event to larger themes or topics√≥that close off possibilities and hem in interpretations. But we also have choices√≥about what we teach and how we teach. I have used the scholarship of teaching and learning to develop new strategies for integrating visual materials with other sources to help students comprehend context, to develop their understanding in a way not possible using textual sources alone. My intention is to build scaffolding that helps students to see beyond the simple, to formulate provisional questions for inquiry, to encounter new sources, and then to revise their earlier assertions. In this way, I hope to help students learn the process of historical reasoning. 12 OLIVIA: "'The Industrial life' picture seems to view industrial work in a romanticized light, which contrasts with the way it originally used to be represented. Early in the century, industrial life was seen as unsanitary, dangerous, menial work, fit for only the poor. This picture, however, uses vivid, warm colors, clean cut and clear drawn lines. I think after WWII (this picture was created in 1941) there seemed to be more of a romanticized view of technology and industry and all that can be accomplished. The picture shows 4 types of work being done that are necessary to an industrial society. There's the scientist, the architect, the worker, and I guess the engineer. "The second picture 'Security of the Family' is supposed to represent family life and roles during the 40s. The woman (the mother) is seen holding a child√≥obviously meaning that women were expected to be mothers and child rearers. The Father is seen as being more 'intellectual,' sitting down at the table, seeming to have an important air about him. The girl is drawing, to represent that girls are seen as being artistic. The young boy is playing tennis. It shows that girls are supposed to 'act like girls,' being calm and 'cultured.' Boys seem to have more liberties in their manner of behavior." ARTHUR: "Seymour Fogel's painting, 'Security of the Family,' reminds me of Norman Rockwell's paintings, 'The Four Freedoms.' The Rockwell image from that group that comes to mind most immediately is the one where the child is being tucked into bed with the father looking on holding a newspaper containing terrifying headlines. "Both Rockwell and Fogel are presenting idealized images of American society, but they're different. Fogel is not seeking to portray the warmth and intimacy of the kind that Rockwell seeks to portray. Fogel's figures, drawn in the way that marble might be sculpted into statues, present Family Life as a monumental, larger than life force. "The sky overhead may be gray and over cast, but the mother√≥staring out into the undefined future much as the mother in Lange's 'Migrant Mother'√≥is, like the other members of the family, stolid, sturdy, unwavering in their march forward into the unknown." 13 See Barbara Melosh, Engendering Culture: Manhood and Womanhood in New Deal Public Art and Theater (Washington, 1991). 14 "Exercise Two," History 31516: Power, Race, and Culture in the U.S. City, Fall 2003, City College of New York http://www.ccny.cuny.edu/humanities/jaffee/nyc/exer2.html(Dec. 1, 2005). 15 See Brian W. Dippie, George Catlin and His Indian Gallery (Washington, 2002); Thomas Loraine McKenney, History of the Indian Tribes of North America, with Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of the Principal Chiefs Embellished with One Hundred and Twenty Portraits from the Indian Gallery in the Department of War (3 vols., Philadelphia, 1838√Ī1844); Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650√Ī1815 (New York, 1991); Carrie Rebora, John Singleton Copley in America (New York, 1995). Next essay: Peter Felten, "Confronting Prior Visual Knowledge" >

|