“Famous Americans”: The Changing Pantheon of American Heroes

Sam Wineburg and Chauncey Monte-Sano

Stanford University, University of Maryland

Editor’s note: Additional statistical data not appearing in the print version of this article has been integrated into this online presentation of the article.

Meeting at the Wabash Avenue Young Men’s Christian Association on Chicago’s South Side on September 9, 1915, four African American men laid the foundation for the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (asnlh), the first scholarly society promoting black culture and history in America. The force behind that initiative was Carter G. Woodson, the only black of slave parentage to earn a history Ph.D. from Harvard University. A tireless institution builder, Woodson not only kept the asnlh afloat through years of financial uncertainty, but also established the Journal of Negro History in 1916 and served as its editor until his death in 1950. Woodson authored and edited scores of publications—scholarly monographs, textbooks, pamphlets, newsletters, circulars, and reports—all aimed at spreading knowledge about blacks’ contributions to American history. Yet, even more than his prodigious list of publications, the initiative for which Woodson is best known was inspired by a trend in the 1920s when civic organizations would devote weeks of the calendar to promote special causes, such as Boy Scout Week, Clean-Up Week, or Good Health Week. In 1926, Woodson designated the week in February that included the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln (February 12) and Frederick Douglass (February 14) as “Negro History Week.”[1]

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, black America celebrated Negro History Week with speeches, parades, and educational events. But not until the 1960s did white America take much notice. During the 1940s and 1950s, mainstream textbooks virtually ignored black Americans except in their faceless guise as slaves. “Blacks were never treated as a group at all,” wrote Frances FitzGerald. “They were quite literally invisible.” Textbook narratives of the 1940s and 1950s described the population of the United States with the clause “leaving aside the Negro and Indian population”—and did just that.[2]

Much would change with the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. By 1967 the educator and historian Larry Cuban wrote about a “deluge” of curriculum materials on black history flooding the schools. At the nation’s bicentennial celebration, President Gerald R. Ford invoked Woodson in a proclamation making February “Black History Month,” citing the “too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.” Indeed, Black History Month has become a fixture in the school calendar, often more prominent than the homogenized birthdays of George Washington and Lincoln. The month-long commemoration has become the model for other groups to gain access to the school curriculum, with lesson plans and educational kits backed by congressional resolutions and presidential declarations.[3]

Black History Month still reigns as the crowning example of curricular change, recognized by school celebrations and assemblies, civic commemorations, billboard notices, and television documentaries. Entire generations of Americans have studied textbooks that are a far cry from those FitzGerald lambasted. In 1974, the National Council for the Social Studies inaugurated the Carter G. Woodson Book Award to encourage “the writing, publishing, and dissemination of outstanding social science books for young readers that treat topics related to ethnic minorities and relations sensitively and accurately.”[4] No one scanning the shelves of the “youth biography” section of a school or public library can miss the shift in titles now offered to young people.

Indeed, content analyses of mainstream textbooks show today’s books to be a radical departure from their predecessors, at least in terms of the famous people profiled. When researchers at Smith College’s Center for the Study of Social and Political Change examined books from the 1940s, they found Dred Scott to be the only black figure mentioned multiple times. However, by the 1960s, minorities had “moved to the center stage of American history.” American history textbooks went from “scarcely mentioning blacks in the 1940s to containing a substantial multicultural (and feminist) component in the 1980s.”[5] Some observers pooh-pooh these changes, discounting them as tokenism or, as one analyst put it, “old wine in new bottles.”[6] The historian and professor of Africana studies Allen B. Ballard blasted the very premise of Black History Month and its “apartheid-like assumptions that the other 11 months of the year can be devoted to White history.”[7] Other commentators dismiss changes in textbooks as “mentioning,” a practice in which women and minorities accessorize a curriculum whose basic structure remains intact: Teddy Roosevelt still charges San Juan Hill, only now a few Buffalo Soldiers bring up the rear. Some took the Senate’s ninety-nine to one rejection of the 1995 National History Standards as a testament that traditional history is alive, well, and quite crotchety. “It may be too bad that dead white European males have played so large a role in shaping our culture,” harrumphed Arthur Schlesinger Jr., “but that’s the way it is.”[8]

So the questions remain: Have changes in curriculum materials made a dent in popular historical consciousness? Whom do contemporary American schoolchildren define as the people who “made history”? Do today’s youth envision a pantheon of “famous Americans” still defined by the traditional canon or one that reflects the opening up of history to the previously unstoried? These are the kinds of questions we set out to explore.

A Different Approach

Our approach constitutes a departure from conventional attempts to probe students’ historical knowledge. Rather than convening a group of experts to rehearse the hoary ritual of “do you know what we know,” we instead allowed students to nominate the figures who they believed mattered in American history. In other words, presented with a page of blank lines, whom would today’s high school students list as the most famous individuals from American history?

Our simple questionnaire contained ten blank lines, split into part A and part B.[9] Students filled out surveys in their regular social studies classes after teachers read from the following prompt: “Starting from Columbus to the present day, jot down the names of the most famous Americans in history. The only ground rule is that they cannot be presidents.”[10] After students had completed part A (about five to seven minutes), teachers read these instructions: “Look at Part B. On these five lines, write down the names of the five most famous women from American history. The only ground rule is that they can’t be the wives of presidents.”

We included the restriction about presidents and their wives because pilot testing revealed that some students scribbled the first five names that popped into mind, and these turned out to be the usual suspects—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Bill and Hillary Clinton, or George W. Bush. The restriction made students devote a bit more thought to generating their lists. We also experimented with different wording for the prompt, substituting the words “significant” and “important” for “famous.” Those substitutions yielded little difference in students’ responses, except the feedback that “famous” was the prompt most intuitively understood. During the questionnaire’s testing phase we further noted that students tended to list presidents’ wives whenever a famous president was listed. We therefore introduced the restriction about presidents’ wives and specifically prompted students to list five “famous women” in part B. While students could list either men or women in part A, part B restricted choices to women, which obviously inflated the number of women that appeared on students’ final lists. (In some cases, students who had spontaneously listed women in part A erased them when they reached part B, rewriting those names in that section.) Finally, at the top of the form we asked students to indicate their gender and their race/ethnicity.

We surveyed eleventh and twelfth graders from public high schools in each of the fifty states, collecting in total two thousand responses. We identified schools by using demographic data available on the GreatSchools.net Web site, which provides information about school size, percentage of students eligible for free lunch, racial and ethnic makeup, and course offerings.[11] We sought schools that reflected the overall demographic profile of their region. We called principals and district personnel to explain the goals of the study and to solicit participation. Although our sample was not random (a truly random sample would have meant that everyone in the nation who fit our criteria would have had an equal chance of being surveyed), we worked to make it broadly representative of the demographic pattern of the nation as a whole.[12]

To provide a comparison with the student responses, we surveyed two thousand American-born adults aged forty-five and over. We restricted our sample to American-born adults so we could compare young people, schooled in this country, with a group of adults similarly schooled. We gathered data in thirteen population centers, administering surveys in a host of venues: shopping centers, downtown pedestrian malls, hospitals, libraries, adult education classes, business meetings, street fairs, and retirement communities. The demographics of the adult sample corresponded roughly to the 2000 census. The questionnaire for adults was identical to the one for students, except that it asked year and place of birth.[13]

Who Is a “Famous American”?

Whom do American high school students list as the most famous figures in American history “from Columbus to the present day,” not including presidents or their wives? When we asked teachers and principals whom they thought students would list, they predicted that kids would select celebrities, hip-hop artists, and sports heroes—figures such as Madonna, Michael Jordan, Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson, Paris Hilton, and Tupac Shakur. To be sure, these names were among those listed on students’ surveys, but they were nowhere near the top. Of the thousands of figures whom students listed, only five appeared on a quarter of all lists. Each of the five was a legitimate historical figure. The top three names were all African Americans: Martin Luther King Jr. (far and away the most famous person in American history for today’s teenagers), Rosa Parks (close behind), and Harriet Tubman. Although 67% of the two thousand respondents named King, only about half as many (34%) mentioned the first white name on the list, Susan B. Anthony. The list of the top ten names appears in table 1.[14]

Using logistic regression, we analyzed patterns in students’ responses.[15] Students’ geographic region had almost no influence on their responses, while gender played a somewhat larger role. [16] The most pronounced differences among students’ responses were by race—particularly between African American and white students. For example, even though King appeared on 64% of all white students’ lists, he appeared on 82% of all black students’ lists. Black students were nearly three times more likely than white students to name King, twice as likely as whites to name Tubman and Oprah Winfrey, and 1.5 times as likely to name Parks. Students’ race also predicted their likelihood of naming other figures in the top ten. For example, white students named every white figure at significantly higher rates than did blacks. The differences between white and black students can be seen in their respective top ten lists. Five names overlap: the four African American figures and Anthony. Whereas black students’ top ten is dominated by nine black figures, white students’ top ten combines whites and blacks.

Table 1

Students’ top ten list of famous Americans

| Famous American | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 1. Martin Luther King Jr. | 67 |

| 2. Rosa Parks | 60 |

| 3. Harriet Tubman | 44 |

| 4. Susan B. Anthony | 34 |

| 5. Benjamin Franklin | 29 |

| 6. Amelia Earhart | 23 |

| 7. Oprah Winfrey | 22 |

| 8. Marilyn Monroe | 19 |

| 9. Thomas Edison | 18 |

| 10. Albert Einstein | 16 |

Top ten “most famous Americans” listed by two thousand high school students in 2004–2005, and the percentage of students who listed them. Source: Based on Sam Wineburg and Chauncey Monte-Sano survey conducted between March 2004 and May 2005 of two thousand high school juniors and seniors at American public high schools in all fifty states.

A Common Pantheon?

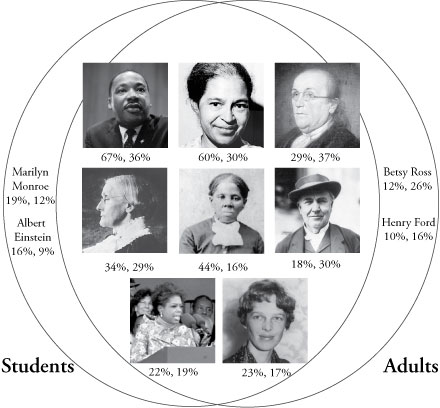

Contrary to our expectations, instead of a wide divergence separating young people from adults, we found remarkable overlap. Among the ten most named figures for young people and adults, eight were identical. (See figure 1.) For adults, no name approached the overwhelming presence of King or Parks on the students’ lists (67% and 60%, respectively, on students’ lists, compared to 36% and 30% on adults’ lists). Anthony was the only figure in the top five whose presence was comparable for young people and adults.

Figure 1. This diagram shows the overlap between students’ and adults’ lists of ten “most famous Americans.” Students and adults listed eight of the same names: Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Benjamin Franklin, Susan B. Anthony, Harriet Tubman, Thomas Edison, Oprah Winfrey, and Amelia Earhart. The first number indicates the percentage of students who named that person as a “famous American”; the second number indicates the percentage of adults who named that person. Source: Based on two Sam Wineburg and Chauncey Monte-Sano surveys: the first was conducted between March 2004 and May 2005, surveying two thousand high school juniors and seniors at American public high schools in all fifty states; the second was conducted between June 2005 and August 2005, surveying two thousand American-born adults aged forty-five and over in thirteen population centers in the United States. Martin Luther King Jr. photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, LC-DIG-ppmc-01269; Rosa Parks photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-109426; Benjamin Franklin portrait courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, LC-USZ62-101098; Susan B. Anthony photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-23933; Harriet Tubman photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-7816; Thomas Edison photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-67859; Oprah Winfrey photo courtesy Office of Public Affairs, Corporation of National and Community Service; Amelia Earhart photo courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-20901.

Region played a greater role in adults’ responses than it did in students’ responses. Adults in “blue” states (based on states that voted Democratic in the 2004 presidential election) were more likely than those in “red” states (those that voted Republican) to name many of the figures in the top ten. However, as with students, the most striking difference among adults was by race. Black and white adults shared five names in the top ten, one white and four black: Benjamin Franklin (who appeared in the first position for whites and the tenth for blacks), King, Parks, Winfrey, and Tubman. Whites were significantly more likely than blacks to name the white figures in the top ten; blacks were significantly more likely to name black figures.

Within each age group, African Americans and whites shared five common names. However, we see more agreement when comparing racial groups across generations. For example, black adults and teens shared seven of ten names, all African Americans. White students and adults shared eight of ten names, four African American and four white. The effects of race are noteworthy, but so too are the effects of age. Overall, students were more than four times as likely as adults to name King and Tubman, and almost four times more likely to name Parks.

The Changing Fortune of Fame

A questionnaire is a blunt instrument, and ours was no exception. Beyond some basic characteristics—age, gender, region of the country, race, and ethnicity—we know little about our respondents. Asking people to name “famous” Americans combines the virtues of open-endedness with the defects of imprecision. Although we tested this and other prompts (“famous,” “significant,” and “important” Americans) with teens and found few differences among the alternatives, we used the same prompt for adults, a decision dictated less by the belief that “famous” means the same thing to adults as to teens than by the press for consistency with a survey instrument. Prompting respondents for five women’s names obviously inflated the number of women listed, but we are at a loss to say precisely how many. As we take stock of our results, we are humbled by the complexity of the question we addressed—who defines the historical canon for contemporary Americans?—and the imperfect tool we used to address it.

Yet, despite those many qualifications (and we could list more), we are struck by a pattern impossible to miss in the responses of our four thousand Americans.[17] Even our questionnaire’s many shortcomings cannot mist the clarity of consensus that emerged among Americans of different generations. Some eighty years after Woodson initiated Negro History Week, Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks have emerged as the two most famous figures in American history, with Harriet Tubman close behind. While some of the old standbys still appear—Benjamin Franklin defines resilience in our time no less than in his own—the prominence of African Americans at the top of our lists is the most remarkable finding of this survey. Whether these four thousand Americans truly embrace diversity in their hearts is a question no computer rifling through strings of numbers can answer. But the simple thought experiment of imagining such results four decades ago, on the eve of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (a time when the Federal Bureau of Investigation was wiretapping King’s house and bugging his hotel rooms; when a 430-page National Educational Association guide for teachers promoting “critical thinking” ignored black Americans except for three pages on slavery; when a search under T in the index of a typical history textbook would have failed to turn up a single “Tubman, Harriet”), brings into crisp focus just how dramatic this shift has been.[18]

In the process of turning King, Parks, and Tubman into icons of freedom’s struggle, other struggles get left behind. Susan B. Anthony achieves prominence, but other leaders of woman suffrage go unlisted (Elizabeth Cady Stanton appeared on only 5% of teens’ and adults’ lists). César Chávez appeared on 13% of California students’ lists, but a scant 2% nationwide. Sacagawea was in the eleventh slot on students’ lists, but the next most famous Native American, Pocahontas, appeared on less than 5% of lists. Four out of two thousand students and one of two thousand adults named the muckraking journalist Upton Sinclair. Prominent figures from American labor were nonexistent on both teens’ and adults’ lists. Among our 4,000 questionnaire responses there was not a single mention of Samuel Gompers or Eugene V. Debs. America’s multihued movement for equality—that variegated and textured struggle enlisting Americans of all stripes, colors, and political persuasions, engaging Native Americans, Chinese and Japanese, Hispanics and Irish, Jews and Catholics, and successive waves of immigrants, laborers, union organizers, and reformers of all social classes—has been seemingly reduced to an equation of black and white.

Although black civil rights leaders top our lists, it is instructive to consider which figures have lost cachet over time. For example, Booker T. Washington, one of the few blacks (with Dred Scott) named in textbooks in the first half of the twentieth century, appeared on only 2% of white students’ lists and 7% of those of black students. Frederick Douglass appeared on 2% of white students’ surveys and 11% of black students’ surveys.

The muted presence of Douglass, Booker T. Washington, or, for that matter, W. E. B. Du Bois (named by 1% of white students and 5% of black students), stands in contrast to the remarkable prominence of Harriet Tubman, the third most famous American for students and ninth for adults. Tubman’s presence was inversely related to the age of our respondents: 11% of the oldest adults named her, compared to 19% of younger adults and 44% of students.[19] Even though Tubman’s exploits occurred during the Civil War, her prominence in American memory is relatively recent. An analysis of history textbooks of the 1940s and 1950s, such as Fremont Philip Wirth’s United States History, David Saville Muzzey’s 1952 edition of A History of Our Country, or Canfield and Wilder’s Making of Modern America, reveals not a single mention of Tubman.[20]

We can track Tubman’s rising star by following the successive editions of Thomas Bailey’s 1956 The American Pageant—one of the longest-running textbook titles, it is commonly used in college survey courses and in high school Advanced Placement courses. (American Pageant is now in its thirteenth edition, with David M. Kennedy as first author.) The first and second editions devote nearly a page to runaway slaves, including a map of zigzagged routes throughout the Northeast to the free-soil haven of Canada, along with explanations of freehouses and the abolitionist “conductors.” But no Tubman. Not until the 1971 fourth edition does she appear, accompanied by these two sentences: “The most amazing of these ‘conductors’ was an illiterate runaway slave from Maryland, fearless Harriet Tubman. During night forays into the South, she rescued more than 300 Negroes, including her aged parents, and deservedly earned the title ‘Moses.’” A line drawing of Tubman accompanies the explanation, with the caption “Premier Assistant of Runaway Slaves.” The same drawing was retained until the 1983 edition, when a photograph, showing Tubman in formal dress, replaced it. In the 2006 edition, this photo and caption of Tubman take up over a quarter of a page. Additionally, an adjoining sidebar quotes Tubman’s reaction to John Brown’s execution.[21] Compare Tubman’s rising fortunes to the checkered fate of another Civil War–era Harriet, Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold more than 300,000 copies in its first year, more than any other book save the Bible. Whereas Tubman was the third most named American for students and the ninth for adults, Stowe was twenty-second for students and twenty-sixth for adults. The difference between the Harriets becomes more pronounced when we inspect books on each woman published for the juvenile market. From 1984–2003, three biographies of Tubman were published for every one of Stowe (forty for Tubman and thirteen for Stowe). Indeed, an analysis of the top hundred figures listed by students, and the number of juvenile biographies published about each figure from 1984–2003, yielded a statistically significant correlation. As every introductory statistics book notes, correlation does not mean causation. But a correlation of this magnitude (r = .64) is a rare occurrence in the social sciences and cannot be ignored.[22]

Unlike textbooks, trade books reach well beyond the school curriculum. They are marketed to libraries, bookstores, and directly to parents and children. Similarly, while textbooks typically remain in school at the end of the day, trade books find their way into the home. Parents and grandparents read them to children; and children, especially elementary schoolchildren, still prepare book reports and show them to their parents. When those parents go off to work and there is an occasion to think about a figure from America’s past, they are bound to be influenced by the materials encountered through their school-aged children.[23]

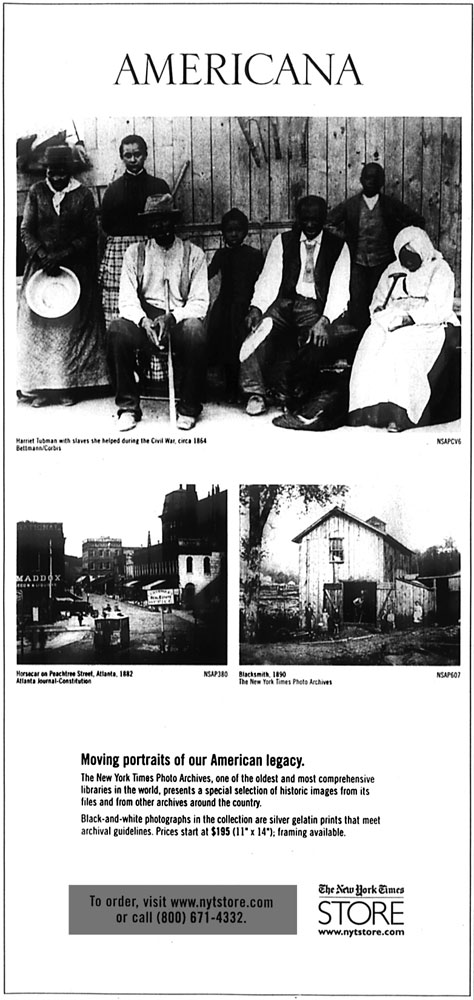

None of this is meant to imply that broad changes in American students’ pantheon of heroes are the direct results of publishing decisions at Scholastic or HarperCollins. Modern society creates historical beings through an unsystematic and chaotic “cultural curriculum” of which textbooks and youth biographies constitute two of many parts. Whether it is King’s “I Have a Dream” speech available in a convenient foldout edition at the check-out stand of a 7-Eleven; an ill-tempered Tony Soprano grumbling about Columbus Day revisionists on The Sopranos; an episode of The Simpsons in which Bart hobnobs with delegates of the Constitutional Convention; a bus poster bearing the iconic visage of Rosa Parks (see figure 2); or a New York Times “Americana” ad hawking a $195 photo of Harriet Tubman (see figure 3), the cultural curriculum is so much a part of our landscape that it rarely comes into view as an educating force.[24]

Figure 2 (top). This poster of Rosa Parks was displayed on Seattle’s Metro Transit buses in 2006. Figure 3 (bottom). This New York Times advertisement for its collection of historical “Americana” photos features an image (top) of Harriet Tubman (far left, with hat) standing with a group of slaves she helped during the Civil War. Images such as these remind us that historical consciousness is developed in more places than just our schools. Rosa Parks poster courtesy Titan Worldwide. New York Times advertisement reprinted from New York Times, Jan. 2, 2006, p. A12. © Bettmann/Corbis and courtesy New York Times.

Figure 2 (top). This poster of Rosa Parks was displayed on Seattle’s Metro Transit buses in 2006. Figure 3 (bottom). This New York Times advertisement for its collection of historical “Americana” photos features an image (top) of Harriet Tubman (far left, with hat) standing with a group of slaves she helped during the Civil War. Images such as these remind us that historical consciousness is developed in more places than just our schools. Rosa Parks poster courtesy Titan Worldwide. New York Times advertisement reprinted from New York Times, Jan. 2, 2006, p. A12. © Bettmann/Corbis and courtesy New York Times.

Rather than being taken literally, the notion of a cultural curriculum is better understood as a “sensitizing concept” that points to the distributed nature of learning in modern society, warning us of the comforting, albeit fallacious, notion that historical consciousness develops rationally and sequentially through efforts to create and deliver a state-mandated curriculum. The cultural curriculum takes many courses, some running in opposite directions, others crisscrossing madly, and still others resembling parallel lines that stubbornly refuse to meet. But when the courses of this curriculum do meet and we can discern trends coming from different directions and echoing from varied quarters, the cultural curriculum’s effects become most powerful. Above all, the cultural curriculum reminds us not to confuse schooling with education: the latter being, in Bernard Bailyn’s words, “the entire process by which a culture transmits itself across generations.”[25]

A Shortage of Myths?

It has become a national pastime to give kids a test and then wag our fingers at their ignorance. Yet, not in 1915, the date of the first administration of a large-scale objective history test, nor in any of the subsequent administrations—1942, 1976, 1987, 1994, or 2001—were the questions that were put to children also put to adults.[26] Such a convenient oversight permits each generation to marinate in the self-satisfaction that, back in their day, they knew their Andrew Johnsons from their Lyndon B. Johnsons.

Our approach differed from previous efforts in two ways. First, we did unto adults as we did unto children. Second, rather than ensnaring both groups with I-gotcha multiple-choice items (tweaking our almost-right “distracters” in the manner of professional testing companies), we took a different tack. We presented our respondents with only minimal instructions and ten blank lines.

Although a few students, like a few adults, clowned around, most took it seriously. (About an equal number in both groups put down “Mom” as one of their famous Americans; from students—obviously adolescent boys—we learned that Jenna Jameson is the biggest star of the X-rated movie industry.) However, when we step back from our findings, we see the same small set of names at the top of all lists. Although the biggest variations were recorded between white and African American respondents, the extent to which white Americans now place black Americans at the top of their lists is remarkable. In this regard, our findings suggest some very different trends from those who fretted that opening up the historical canon to women and minorities would be the downfall of a national historic culture.

The late Arthur Schlesinger sounded the worriers’ call in his best-selling book The Disuniting of America. Drawing on the statements of the most extreme multiculturalists and Afro-centrists of the 1980s and early 1990s, Schlesinger warned that, left unabated, the belittling of unum at the hands of a pugnacious pluribus would tear our schools asunder—and with them our communities and national identity. “If left unchecked,” he wrote, “the new ethnic gospel” would lead inexorably to the “fragmentation, resegregation, and tribalization of American life.”[27]

If we trained our gaze today on the most strident and extreme views out there, we too could come up with a similar prediction of impending doom. But that is not what we did. We looked for ordinary people—teenagers in public school classrooms and adults eating lunch in downtown Seattle, taking a break on a bench in a pedestrian mall in Oklahoma City, or shopping for crafts at a street fair in Philadelphia. What we found was the opposite of “fragmentation, resegregation, and tribalization”: different generations and different races congregated around five or six common names with astounding consistency. While it is not surprising to learn that one of these names was Martin Luther King Jr., who would have predicted Rosa Parks would be the second most named American? Or that Harriet Tubman would be third for students and ninth for adults? Or that forty years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the three most common names appearing on students’ surveys in an all-white classroom in Columbia Falls, Montana, would be of African Americans? For many of those students’ grandparents, this moment would have been unthinkable.[28]

Compare our efforts to other surveys addressing the same general question. In 2006 the Atlantic Monthly asked ten distinguished historians to nominate the one hundred most “influential” Americans.[29] Recognizing the many problems associated with comparing “influential” to “famous,” it is still instructive to look at the similarities and differences between the Atlantic Monthly list and our own. Eliminating presidents and presidents’ wives from the Atlantic Monthly list, we registered overlap with several names: Benjamin Franklin, Martin Luther King Jr., Thomas Edison, and Henry Ford. But number three on the historians’ list was John Marshall—a name mentioned just twice by our four thousand respondents. Conversely, Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman (the number two and three slots for teens, and the third and ninth slots for adults) did not even make it into the historians’ top one hundred (although Lyman Beecher and James Gordon Bennett did). Susan B. Anthony, near the top of our list, languishes at number thirty-eight for historians, behind Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Walt Disney, Jackie Robinson, and Jonas Salk. Among living Americans, Bill Gates, James D. Watson, and Ralph Nader appeared in the historians’ top one hundred.

Oprah Winfrey’s absence from that list points to the gaping differences between academic historians and the ordinary Americans who responded to our survey. In contrast to historians, our four thousand respondents made Winfrey the seventh most named American in history—indeed, the only living figure to appear in the top ten, crossing divisions of age, race, region, and gender.[30]

Trying to capture Winfrey’s influence on American life by confining her role to tv host is like trying to capture Benjamin Franklin’s influence by calling him a printer. With assets exceeding $1 billion, Winfrey is the richest self-made woman in America. In addition to owning her show, she is a magazine publisher, a movie studio magnate, an inspirational speaker, a diet and life coach, an advocate for survivors of sexual abuse, a king-maker (think Dr. Phil), the benefactor of schools and community organizations in the United States and abroad, and a major philanthropist, donating $53 million of her money to charities in 2006, more than any other celebrity. Her Book Club of the Air, launched in 1996, has arguably done more to promote reading in the United States than any initiative since the Great Books program of the 1950s. During the 1996 “mad cow” scare, she aired a program on “Dangerous Food,” vowing never to eat another hamburger. Soon thereafter, U.S. cattle futures tanked, leading to a suit by ranchers in the Texas panhandle for what they called the “Oprah crash.”[31]

Although the other African Americans in the top ten—King, Parks, and Tubman—are present largely due to their role in the struggle for racial equality, Winfrey’s message of self-improvement, personal responsibility, and overcoming adversity transcends race. This contemporary Horatio Alger story features a poor girl who shuttled between her mother in Milwaukee, her grandmother in Mississippi, and her father in Tennessee; who was raped by a teenage cousin and molested by one of her mother’s boyfriends; and who, after starting as a newscaster for a Tennessee radio station appealing to black listeners, achieved phenomenal success against stacked odds.[32]

The majority of Winfrey’s fan base does not resemble her, if “resemblance” is defined by that classic American metric, the color line. The principal demographic for her afternoon show is white women between the ages of 18 and 54; the typical reader of O Magazine is a white woman earning $63,000, partial to Lexus sedans and Coach purses. Although African American viewers perceive Winfrey’s race as central, white viewers report that her race is “not important,” simply one characteristic among many in a rich palette of attributes: her weight, her past traumas, her spiritual beliefs, her charity work, her openness and honesty, her moral message, her intelligence, or her humble roots.[33] Less than seventy years ago, the Daughters of the American Revolution canceled a performance by Marian Anderson at their Constitution Hall when they realized she was black. It is highly probable that their granddaughters and great-granddaughters comprise part of the subscription base of O Magazine and are among the audience members who each paid $185 to attend Winfrey’s “Live Your Best Life” tour.

Old Heroes, New Heroes

Another study similar to ours was undertaken by Michael Frisch, who over a fourteen-year period asked college students at the State University of New York at Buffalo to list “the first ten names that popped into their head” from the beginning of American history to the end of the Civil War. Students completed the exercise twice, once including presidents and then excluding “presidents, statesmen and generals.” Like us, Frisch was struck by the consistency of his results across cohorts of undergraduates between 1975 and 1988 and a comparative sample of college students from Pennsylvania State University. On the “non-presidents” list, two names, Betsy Ross and Paul Revere, lodged at the top, barely budging from the top two spots for the better part of a decade. Ross topped the list in seven of eight years, a finding Frisch referred to as the “Ross hegemony,” a “record that cries out for explanation,” one that “expresses deep, almost unconscious and mythic yearnings.” “Betsy Ross,” he wrote, “exists symbolically as the Mother, who gives birth to our collective symbol.” Paul Revere, “the horse-borne messenger of the revolution,” exerted a similar hold.[34]

But not here. To be sure, Ross and Revere are present among our responses, but their stars have dimmed. Overall, Ross appeared on 12% of students’ lists (thirteenth overall), but for adults (many of whom were the same age as Frisch’s college students in 1984) she still occupies the sixth slot, appearing on 26% of all lists. Revere has fallen from his horse. He is forty-third for students (appearing on only 3% of lists) and thirty-sixth for adults (on 5% of lists).

If to a previous generation Revere and Ross were the father and mother of one kind of myth, surely King and Parks are the founding couple of another. Although we did not ask our high school respondents what they knew about the names they listed, we have spent enough time in classrooms to make educated guesses about what we might hear. King, we surmise, would be cast as the benevolent champion of democracy and civil rights, whose Gandhi-like stance heralded the end of segregation and institutional racism. We doubt that many high school students in an all-white classroom in Montana (or anywhere else) would recognize the King who told David Halberstam in 1967 “that the vast majority of white Americans are racists, either consciously or unconsciously”; the King who linked American racism to American militarism, calling both, along with economic exploitation, the “triple evils” of American society; the King who characterized the bloodbath in Vietnam as a “bitter, colossal contest for supremacy” with America as the “supreme culprit”; or the King who in a speech two months before his assassination accused America of committing “more war crimes almost than any nation in the world.”[35]

We would also expect to hear similar sanitizations of Rosa Parks, fairy tale stories of an unassuming old lady (she was forty-two years old) whose only thought was resting her tired feet after a long day on the job and whose humble and courageous act of defiance single-handedly sparked the bus boycott that led to the end of segregation and Jim Crow.[36] We would not expect any mention of Parks’s sojourn at Myles Horton’s Highlander Folk School, where she was trained in the tactics of nonviolence; no trace of the sixty-eight political organizations for blacks in Montgomery; no awareness of fifteen-year-old Claudette Colvin, who on March 2, 1955, nearly eight months before Parks’s arrest, refused to give up her seat to a white rider and was forcibly removed from a bus.[37] Colvin was following in the footsteps of other black women—Geneva Johnson, Viola White, Katie Wingfield, Epsie Worthy—whose names are absent from the history books although they were similarly ill-treated and sometimes beaten, when they stood up to the power of Montgomery City Lines. Each of these women acted prior to Parks’s arrest in 1955. Yet to speak of them would undermine the tale of a browbeaten seamstress who possessed the unrivaled courage to demand what any twenty-first-century citizen recognizes as inalienable: the right to take one’s seat. Instead of a story about a mass-organizing movement—a narrative of empowerment and agency among ordinary people who in a single weekend printed 52,500 leaflets (enough, and then some, for every member of Montgomery’s black community) and distributed them to churches while organizing phone trees and Monday morning car pools so that no one would have to walk to work—we meet the singular figure of Mrs. Parks. Together with King, she sets out on her civil rights walkabout, only to return to lead a passive and faceless people in their struggle for racial equality.[38]

Sounding a call similar to Schlesinger’s, Bruce Cole, the chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, recently worried that today’s students are ignorant of the history that provides a common national bond. To remedy this, he has commissioned forty laminated posters to be distributed to high schools across the country, including Grant Wood’s 1931 painting The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere. “You can call them myths if you want,” averred Cole, “but unless we have them, we don’t have anything.”[39]

Cole needn’t worry about an impending myth shortage. Myths fill the national consciousness the way excited gas molecules fill a vacuum. When has our stockpile of myths been so depleted that we needed an emergency infusion of laminated posters? As one set of myths goes backstage others jostle in the wings, waiting for their moment. In a nation as diverse as ours, we instinctively search for symbols—in children’s biographies, coloring contests, the next Disney movie—that allow us to rally around a common name, event, or idea. As Alon Confino has written, national memory demands compromise and requires adulteration. Rather than consistency, memory is “constituted by different, often opposing, memories that, in spite of their rivalries, construct common denominators that overcome on a symbolic level real social and political differences.”[40]

The common denominators that today draw together Americans of different colors, regions, and ages look somewhat different than those of former eras. While there are still some inventors, entrepreneurs, and entertainers, the people who come to the fore are those who acted to expand rights, alleviate misery, rectify injustice, and promote freedom. Even if the narratives people hold about those individuals are denatured, distorted, decontextualized, and declawed, the fact that they are told in Columbia Falls, Montana; Cranston, Rhode Island; Little Rock, Arkansas; Saratoga Springs, New York; and Anchorage, Alaska seems at this juncture to be deeply symbolic of the national story we tell ourselves about who we think we are . . . and perhaps who we aspire to become.

Sam Wineburg is professor of education and of history (by courtesy) at Stanford University, and Chauncey Monte-Sano is an assistant professor of education at the University of Maryland.

The Spencer Foundation (grant no. 32868) graciously supported this work. However, the authors alone are responsible for the contents of this article. We extend our thanks to Stefanie Talley and Samantha Shepard, our two Stanford undergraduate researchers who played an indispensable role in getting the research underway, and to the Stanford Undergraduate Research Fund for supporting them. We also thank Karina Brossmann, Matt Delmont, Penny Lipsou, Kristen Nelson, Shoshana Wineburg, and Melissa Winter for help in data collection; Eric Acree of Cornell University for his help in locating references; Susan Smulyan and Greg Kaster for help in locating research assistants; and David Kennedy for providing photocopies from early editions of The American Pageant. Songhua Hu and Catherine Warner provided invaluable statistical assistance. Fred Astren, Elliot Eisner, Michael Frisch, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Eli Gottlieb, Daisy Martin, Susan Monas, Mary Ryan, John Seery, Peter Seixas, Lee Shulman, David Thelen, David Tyack, Joy Williamson, Suzanne Wilson, Bob Wineburg, Shoshana Wineburg, and Jonathan Zimmerman provided helpful feedback at different stages of this journey. Scott Casper’s keen editorial eye improved this article beyond measure. This study would have never materialized without the intellectual spark of Ariel Duncan nor been completed without the support and encouragement of Roy Rosenzweig. This article is dedicated to his memory.

Readers may contact Wineburg at wineburg at stanford dot edu and Monte-Sano at chauncey at umd dot edu.

[1] Jacqueline Goggin, Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History (Baton Rouge, 1993), 1, 33. L. D. Reddick, “Twenty-five Negro History Weeks,” Negro History Bulletin, 13 (May 1950), 178.

[2] Frances FitzGerald, America Revised: History Schoolbooks in the Twentieth Century (New York, 1979), 84. Frances FitzGerald located the clause “leaving aside the Negro and Indian population” in the introduction of David Saville Muzzey, A History of Our Country: A Textbook for High School Students (Boston, 1950), 3.

[3] Larry Cuban, “Not ‘Whether?’ But ‘Why?’ and ‘How?’: Instructional Materials on the Negro in the Public Schools,” Journal of Negro Education, 36 (Autumn 1967), 434. For one of the first textbooks on black history from a major publisher (Scott Foresman), see Larry Cuban, The Negro in America (Chicago, 1964). “President Gerald R. Ford’s Message on the Observance of Black History Month,” Feb. 10, 1976, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum, http://www.ford.utexas.edu/library/speeches/760074.htm.

For example, in 1981, Women’s History Week (now Women’s History Month) was recognized by a joint resolution of Congress, and later with a declaration by President Jimmy Carter. Four years later, President Ronald Reagan expanded National Hispanic Heritage Week, first recognized by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968, to the four weeks between September 15 and October 15. In February 2006, President George W. Bush signed a resolution to make January American Jewish History Month. Other examples include March as Irish Heritage Month, recognized first by George H. W. Bush; May as Asian Pacific Heritage Month, designated by Carter; and November as American Indian Heritage Month, recognized by George H. W. Bush. For the University of Vermont’s “diversity calendar,” see Federal Heritage Month Celebrations, http://uds.uvm.edu/diversity_calendar.html. Furthermore, in 2000 President Bill Clinton designated June as Gay and Lesbian Pride Month. William J. Clinton, “Proclamation 7316—Gay and Lesbian Pride Month, 2000,” June 2, 2000, The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/print.php?pid=62387; “History of National Women’s History Month,” National Women’s History Project, http://nwhp.org/whm/history.php; “Jewish American Heritage Month, 2006,” April 21, 2006, The White House, http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2006/04/20060421-3.html; Ronald Reagan, “Remarks on Signing the National Hispanic Heritage Week Proclamation,” Sept. 13, 1988, The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency .ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=36365&st.

[4] “ncss Writing Awards,” National Council for the Social Studies, http://www.socialstudies.org/awards/writing/.

[5] Robert Lerner, Althea K. Nagai, and Stanley Rothman, Molding the Good Citizen: The Politics of High School History Texts (Westport, 1995), 71.

[6] Stuart J. Foster, “The Struggle for American Identity: Treatment of Ethnic Groups in United States History Textbooks,” History of Education, 28 (Sept. 1999), 266.

[7] John Hope Franklin et al., “Black History Month: Serious Truth Telling or a Triumph in Tokenism?,” Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 18 (Winter 1997–1998), 91.

[8] On “mentioning,” see Harriet Tyson-Bernstein, A Conspiracy of Good Intentions: America’s Textbook Fiasco (Washington, 1988). On the U.S. Senate rejection of the 1995 National History Standards, see Gary B. Nash, Charlotte Crabtree, and Ross E. Dunn, History on Trial: Culture Wars and the Teaching of the Past (New York, 1997). Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society (New York, 1988), 128.

[9] We recognize that paper and pencil measures—even relatively open-ended ones—provide but a glimpse of what students actually know. In two decades of prior work on students’ historical understanding, we have shadowed young people, using ethnographic methods from the beginning of the school year to the end; engaged them in extensive multihour interviews probing them about their understanding of their history classes and course assignments; observed them in the contexts of their homes, engaging them and their parents in interviews and history-related tasks; and studied them in controlled settings as they “thought aloud” about historical documents and artifacts. These labor-intensive approaches yield rich portraits of adolescent understanding, but at the expense of statistical power and generalization. See Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia, 2001); Sam Wineburg, “Crazy for History,” Journal of American History, 90 (March 2004), 1401–14; and Sam Wineburg et al., “Common Belief and the Cultural Curriculum: An Intergenerational Study of Historical Consciousness,” American Educational Research Journal, 44 (March 2007), 40–76. For more information from the surveys, see http://www.journalofamericanhistory.org/textbooks/2008/wineburg/.

[10] We included the phrase “Columbus to the present day” to emphasize that individuals from all eras of American history were appropriate responses. A modified version of this survey was piloted in Wineburg et al., “Common Belief and the Cultural Curriculum.”

[11]GreatSchools.net, http://www.greatschools.net/. Field-testing of the questionnaire began in January 2004; actual data collection started in March 2004 and was completed by May 2005. We mailed questionnaires to the social studies classes after getting permission from the building principal or district administrator. Reading from scripts we provided, teachers told the students that this was “not a test” and that we were solely “interested in understanding how kids like you think about the past.” We assured students that it was okay if they could not think of ten names and left some lines blank. Not all students listed ten names. The administration of the survey took fifteen minutes from start to finish, and teachers returned the questionnaires to us in self-addressed stamped envelopes.

[12] The following racial/ethnic breakdown characterized the 2000 census, with our sample’s corresponding percentages in parentheses: white 69% (70%); African American 12% (13%); Asian American 4% (7%); Native American 1% (1%). In the 2000 census, 13% of Americans said they were of Hispanic origin. Our survey included Hispanic as one of several racial/ethnic categories; 9% of participants checked Hispanic as their racial/ethnic group. All percentages reported here have been rounded. Two percent of the 2000 census’s respondents characterized themselves as biracial. Elizabeth M. Grieco and Rachel C. Cassidy, “Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: Census 2000 Brief,” March 2001, U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census .gov/prod/2001pubs/cenbr01-1.pdf. For our purposes, when students checked more than one category (for example, both Caucasian and Hispanic), we categorized them according to the non-white category they marked. Eighty-two respondents declined to state their race. Because their responses were sufficiently similar to those of the white respondents, we felt reasonably confident in combining the categories into one.

[13] Adult data were collected between June 2005 and August 2006. Our locations were San Francisco, Seattle, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Oklahoma City, Houston, Miami, Philadelphia, Knoxville, Providence, Boston, Detroit, and Minneapolis. Trained research assistants administered surveys individually in most settings. In a few cases, surveys were mailed (for example, to retirement communities) after securing the cooperation of the director, who then administered the surveys using a script we provided (much like the one for students). In terms of matching the 2000 census, the relevant numbers for our adult sample were 79% white (versus 69% in the census), 14% African American (12%), 2% Asian American (4%), 2% Native American (1%), 47% male (49%), 53% female (51%). Because we required that respondents be American-born, our sample underestimated Hispanic adults; in the 2000 census, 13% of Americans indicated Hispanic origin while only 2% of our respondents did so. All percentages reported here have been rounded. Greico and Cassidy, “Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin.”

[14] The analyses looked at the total numbers of times a particular name appeared on students’ lists, not the order in which those names were listed. Our results would look somewhat different if we considered only the first five names students provided (without considering their responses in part B, after they were specifically cued to provide women’s names). Looking at the data that way poses considerable measurement problems. In some cases, students who had listed women in part A erased them when they got to part B, rewriting the names in that section and inserting new male names in part A. Therefore, the following numbers should be interpreted cautiously: Considering only the first five names listed, we see a more gendered view of the data, as we might expect. Martin Luther King Jr. retains his top spot overall, appearing in 67% of the top five slots, but there is a precipitous drop to the next two most listed names, Benjamin Franklin, at 29%, and Thomas Edison, at 18%. Rounding out the top ten are Albert Einstein at 16%, Lewis and Clark, and Malcolm X, at 12%, Michael Jordan, at 11%, and Rosa Parks, Bill Gates, and Henry Ford, each at 10%.

[15] Logistic regression is a statistical technique that compares the effects of two or more factors (“independent variables”) on an outcome of interest (a “dependent variable”). In our case, the outcome of interest was the name of a particular historical figure that a given respondent listed. Logistic regression predicts the likelihood that people possessing a particular attribute or set of attributes (such as belonging to a certain ethnic group or living in a particular region) will name a particular figure. The results of this test are reported as an adjusted odds-ratio (aor), or the likelihood that a person possessing attributes A, B, and C (for example, an African American female from New York) will list a particular name compared to someone with attributes D, E, and F (for example, a Caucasian male from Iowa). Thus, if the aor for African Americans naming Martin Luther King Jr. is two, this means that African Americans are twice as likely as whites to name King. The aor pertains even when other variables—for example, gender or region—are taken into account.

The assumptions of logistic regression are similar to multivariate linear regression. The effects of an independent variable are used to predict the response on a dependent variable by assuming an underlying model in which none of the predictor variables are used, and then each is serially entered into the equation to assess its independent contribution. While linear regression assumes that responses are distributed normally (that is, they correspond to a bell curve), logistic regression makes no such assumption.

[16] In this and all subsequent reporting of statistically significant results, alpha was set to the <.05 level.

[17] Another shortcoming—particularly when comparing the responses of young people with adults—was the different contexts in which the two groups completed the survey. Students filled it out in their classrooms; adults filled it out individually, in a host of different settings. Thus the consensus we noted was even more remarkable. We should also note that logistic regression assumes the independence of responses. For students, surveys were administered in a setting where they studied a common curriculum and used the same textbook; the assumption of statistical independence cannot be maintained in its purity. One could raise a related point for adults: people who eat lunch at the same pedestrian mall during the same hour often work in the same office, follow the same schedule, and sit by one another because they are friends and associates. Pure independence of response is compromised here, too.

[18] William H. Cartwright and Richard L. Watson Jr., eds., Interpreting and Teaching American History (Washington, 1961).

[19] For this analysis, we created another independent variable—age—and included it in the logistic regression equation. We split the adult respondents into two groups: younger adults (aged 45–65) and older adults (aged 66 and above). This age trend holds for each of the four African Americans in the top ten. Adults aged 45–65 were 2.5 times more likely than those aged 66 and above to name King; about twice as likely to name Oprah Winfrey; and 1.5 times more likely to name Parks.

For King, x2 (7)= 197.53. For Tubman, aor= 2.1; x2 (7)=115.22. For Winfrey, aor=1.9; x2 (7)=63.74. For Parks, x2 (7)= 88.56. We divided the adults in this way because analyses revealed that adults from ages 45-65 responded in similar ways, and adults age 66 and over responded similarly, but these two groups differed slightly from one another

[20] See Lerner, Nagai, and Rothman, Molding the Good Citizen. What is taught about Harriet Tubman in children’s books (and even many textbook accounts) is sometimes as much the stuff of legend as documented fact. See Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York, 2006); Kate Clifford Larson, Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero (New York, 2004); and Jean M. Humez, Harriet Tubman: The Life and the Life Stories (Madison, 2003). For a review of curriculum materials, see Michael B. Chesson, “Schoolbooks Teach Falsehoods and Feel-Good Myths about the Underground Railroad and Harriet Tubman,” The Textbook League, http://www.textbookleague.org/121tubby.htm. Fremont P. Wirth, The Development of America (New York, 1936); David S. Muzzey, Our Country’s History (Boston, 1957); Leon H. Canfield and Howard B. Wilder, The Making of Modern America (Boston, 1964).

[21] Thomas A. Bailey, The American Pageant: A History of the Republic (Boston, 1956); Thomas A. Bailey, The American Pageant: A History of the Republic (Boston, 1961); Thomas A. Bailey, The American Pageant: A History of the Republic (Lexington, Mass., 1971), 402, 403; Thomas A. Bailey and David M. Kennedy, The American Pageant: A History of the Republic (Lexington, Mass., 1983); David M. Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, and Thomas A. Bailey, The American Pageant: A History of the Republic (Boston, 2006), 422.

[22] For this analysis, we used the “Biography Index” accessed through WorldCat, a database of the merged catalogs of libraries around the world. Search terms included “juvenile” for intended audience (that is, books intended for children up to age fifteen), the time frame 1984–2003, and a keyword search for the famous person’s name.

[23] We thank Peter Knupfer of Michigan State University for pointing this out.

[24] “‘I Have a Dream’ Entire Speech Available FREE to the Public: Participating 7-Eleven Stores to Offer Commemorative Brochure during Black History Month,” Jan. 31, 2003, press release, The King Center, http://www .thekingcenter.org/news/press_release/2003-01-28.pdf; “Christopher,” in The Sopranos: The Complete Fourth Season, dir. Timothy Van Patten (hbo, 2002), (dvd, 4 discs; hbo Home Video), disc 1; “Bart Gets an F,” in The Simpsons: The Complete Second Season, dir. David Silverman (20th Century Fox Television, 1990) (dvd, 4 discs; 20th Century Fox ), disc 1.

[25] On “sensitizing concepts,” see Herbert Blumer, “What Is Wrong with Social Theory,” American Sociological Review, 19 (Feb. 1954), 3–10; and Bernard Bailyn, Education in the Forming of American Society: Needs and Opportunities for Study (1960; New York, 1970), 14.

[26] J. Carleton Bell and David F. McCollum, “A Study of the Attainments of Pupils in United States History,” Journal of Educational Psychology, 8 (May 1917), 257–74. On the dubious assumptions behind modern multiple-choice tests, see Wineburg, “Crazy for History.” For an effort related to our own in which approximately 1,500 ordinary Americans were surveyed to see how they understood and used the past in everyday life, see Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York, 1998).

[27] Schlesinger, Disuniting of America, 23.

[28] Just how much our findings run counter to conventional wisdom can be seen in a USA Today editorial on Rosa Parks’s death: “Rosa Parks’ name should be familiar to anyone who has taken a history class, but it probably is not.” “One Ordinary Woman, One Extraordinary Legacy,” USA Today, Oct. 25, 2005, http://www.usatoday.com/news/opinion/editorials/2005-10-25-parks-edit_x.htm. Emphasis added.

[29] “The Top 100,” Atlantic Monthly, 298 (Dec. 2006), http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200612/influentials.

[30] When students completed the survey, Parks was alive. Her death, on October 24, 2005, occurred during data collection for adults, when 46% of the surveys were still outstanding. Before October 2005, 25% of adults named Parks; after her death, that number increased to 37%.

[31] See Nancy F. Koehn et al., “Oprah Winfrey,” June 1, 2005, pp. 20, 1, available at Harvard Business Online, http://harvardbusinessonline.hbsp.harvard.edu/hbsp/.

[32] Koehn et al., “Oprah Winfrey,” 3. See also Jeffrey Louis Decker, “Saint Oprah,” Modern Fiction Studies, 52 (Spring 2006), 169–78. The literature on Winfrey’s status as a cultural icon (rather, as the cultural icon) is beyond our scope. Much of it comes out of cultural studies. Consider the following: “Oprah operates as the border zone in which the dialectical relation between the multiple, official discourse that both surrounds and structures the show (including Oprah’s persona), and the unofficial discourses of the participants is played out. . . . The discourses of the dominant culture meet and combine with those of the folk and the everyday to produce the (carnivalesque) process through which new forms of subjectivity are created, which are in part informed by hegemonic forces but which are also separate from them.” If this is typical, it is no wonder that people prefer watching Oprah to reading about her. Sherryl Wilson, Oprah, Celebrity and Formations of the Self (New York, 2003), 6.

[33] Patricia Sellers and Joshua Watson, “The Business of Being Oprah,” Fortune Magazine, 145 (no. 7, 2002), 50–64. Janice Peck, “Talk about Racism: Framing a Popular Discourse of Race on Oprah Winfrey,” Cultural Critique, 27 (Spring 1994), 91.

[34] Michael Frisch, “American History and the Structures of Collective Memory: A Modest Exercise in Empirical Iconography,” Journal of American History, 75 (March 1989), 1130–55, esp. 1146, 1147.

[35] David Halberstam, “The Second Coming of Martin Luther King,” Harper’s Magazine, 235 (Aug. 1967), 48. The “triple evils” quotation is from King’s last address to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, on August 16, 1967. Martin Luther King Jr., “Where Do We Go from Here?,” in A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. James Melvin Washington (San Francisco, 1986), 250; for the Vietnam War and war crimes quotations, see Martin Luther King Jr., “Drum Major Instinct,” Feb. 4, 1968, sermon, Martin Luther King Papers Project Sermons, http://www.stanford.edu/group/King/publications/sermons/680204.000_Drum_Major_Instinct.html.

[36] Herbert Kohl, She Would Not Be Moved: How We Tell the Story of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott (New York, 2007).

[37] Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson (Knoxville, 1987), 39; Larry Copeland, “Parks Not Seated Alone in History,” USA Today, Nov. 28, 2005, http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-11-28-montgomery-bus-boycott_x.htm.

[38] On the “Lone-Ranger theory of historical change,” in which blacks “either . . . failed to resist in the face of overwhelming odds, or they waited for a messianic figure to set them free,” see Michael Eric Dyson, I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York, 2000), 297.

[39] Judith H. Dobrzynski, “Our Official History Scold: The Head of the National Endowment for the Humanities Stands Up for American Exceptionalism,” Wall Street Journal, May 22, 2007, http://www.opinionjournal.com/la/?id=110010109.

[40] Alon Confino, “Collective Memory and Cultural History: Problems of Method,” American Historical Review, 102 (Dec. 1997), 1399–1400.