Markers indicate locations discussed in this article; click on a marker for more details about a location.

French Quarter

Bordered by the Mississippi River, Canal, Esplanade, and Rampart streets, the French Quarter is the original site of New Orleans. It is also known as the Vieux Carré, or the “Old Square.” More >

Lower Ninth Ward

Border by St. Bernard Parish, the Florida Canal, the Industrial Canal, and the Mississippi River, the Lower Ninth Ward is one of the last districts to be developed in New Orleans. More >

St. Bernard Parish

St. Bernard Parish is a predominantly white residential area. Breaches in the Industrial Canal flooded the community during Katrina. More >

Uptown/Downtown

In New Orleans Uptown and Downtown describe large sections of the city in respect to Canal Street and the Mississippi River, not individual neighborhoods. More >

What Does American History Tell Us about Katrina and Vice Versa?

Lawrence N. Powell

Journal of American History, 94 (Dec. 2007), 863–76

Natural disasters invariably provoke a range of reactions. Bereavement mingles with anger. The need to commemorate competes with the urge to blame. Boosterism gets a boost. No matter how deep the ash or how high the rubble, you will always find a politician or business leader promising to bring back a just-ruined city bigger and better than before. Storms, fires, earthquakes, mudslides—these are mere blessings in disguise. What was broken, dysfunctional, and decrepit has been leveled or swept away. Now, long-overdue improvements can finally be launched. The optimistic narratives of resilience and resurrection, so necessary for marshaling the will and the capital to rebuild in the teeth of catastrophe, fill the pages of American urban history. They resounded after the great Chicago fire of 1871 and the Galveston hurricane of 1900. In San Francisco after the earthquake and fire of 1906, local boosters styled themselves “regenerators,” to let people know they were as interested in purification as in rebuilding.[1] Mayor C. Ray Nagin of New Orleans’s pledge to restore the waterlogged metropolis to all its former grandeur, and then some, echoed that language of rebirth and renewal. The businessmen and developers, civic leaders and college presidents, who dominated his Bring New Orleans Back Commission (bnobc) repeated it as well, even as many of them favored shrinking the city’s footprint. President George W. Bush paid boosterism the ultimate compliment when he told a national television audience from a mostly darkened French Quarter seventeen days after the storm: ‘’We will not just rebuild, we will build higher and better.’’[2]

Natural disasters also have political effects. Without fail they shift the ground of local politics. The looting that inevitably follows catastrophe triggers repressive measures. To restore law and order, the militia comes to town. The police are told to shoot to kill. Vigilantes are given license. In a short time, the assault on civil liberties elicits a democratic backlash, if not challenges in the courts. Then there is the political opportunism of the business community, which tends to view crises as terrible things to waste. Good-government forces set up ad hoc committees. They convince state legislatures to set aside locally elected officials. The Galveston plan—the shorthand term for the city-manager-and-commission form of government urban Progressives embraced in order to end boss rule—began as a recovery response to the terrible hurricane of 1900.[3]

Natural disasters can also reverberate through national politics. The great Mississippi flood of 1927 made Herbert Hoover’s reputation, spurred the passage of the most comprehensive flood control measure in the nation’s history, and helped launch the career of Huey P. Long, himself a force of nature. Like wars and depressions, natural catastrophes can serve as detonating events, to use the late Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s evocative language, nudging history’s cyclical movement in a new direction—in the present case toward civic engagement. It is always dangerous for historians to predict the future; most of us get vertigo simply peering over the brink of the present. Even so, enough perspective has opened up in the eighteen months since Hurricane Katrina to venture a cautious judgment. That judgment is partly based on the scope and magnitude of the devastation wrought by the storm—more than a million people exiled from their homes, a displacement dwarfing that of the dust bowl; and $80 billion in property damage, the greatest financial loss in American history. Those statistics alone lift the weather event of August 29, 2005, into the record books. But there is mounting evidence that Katrina may be starting to register in the political almanac as well, surpassing anything experienced by the United States in the past century, including the attack on the World Trade Center, “other than the world wars,” according to one disaster recovery expert.[4]

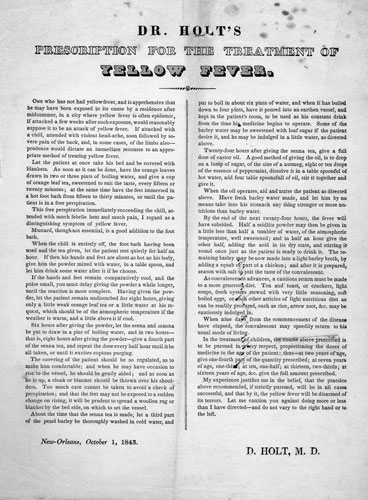

During the nineteenth century, as much as one third of the population of New Orleans evacuated the city between July and October, fearing the diseases that spread during those months. Yellow fever, cholera, malaria, and smallpox were among those poorly understood and often untreatable diseases that preyed upon the city’s residents.

Major epidemics of yellow fever, nicknamed Yellow Jack and Bronze John, raged through New Orleans in 1853, 1878, and 1905. During the 1853 epidemic, an estimated eight to eleven thousand inhabitants of the city died. Many of the dead were quickly buried in shallow mass graves, and the cemeteries literally overflowed with rotting corpses, due to the heat, torrential rains, and the city’s famously high water table.

To fight the disease, the city burned “smoke pots” in the streets to combat the infectious “miasma” or foul air that nineteenth-century experts believed caused most disease. Inadvertently, the smoke did help kill mosquitoes, the source of yellow fever. It was not until the early twentieth century that scientists identified mosquitoes as the carrier of the disease and pinpointed the stagnant water in the New Orleans’s gutters, cisterns, and swamps as their breeding ground. Those discoveries allowed public health officials to effectively combat yellow fever by removing its causes and alleviating the squalid and overcrowded living conditions among the poor that contributed to the spread of the disease.

American politics have been in a conservative phase for so long—thirty-five years and counting—that it is hard to imagine an abrupt shift in the national Zeitgeist happening anytime soon. Although the past forty years of scholarship have enriched our understanding of ethnocultural conflict, gender, and race in American history, we should not lose sight of how much the tension between capitalism and democracy has also driven politics in this country—the yin and yang of our national creed. One generation worships the free market, spares nothing in the pursuit of profit, and turns inward. A succeeding generation, whether bored by material comforts or troubled by the growing polarization of rich and poor arising from unrestrained growth, embraces equality and social solidarity and calls for a turn to affirmative government.From the Richard M. Nixon presidency to the current administration, the watchword has often been wealth more than commonwealth. Jimmy Carter’s conservative presidency did not reverse the trend. Nor did the centrist Clinton administration, with its zeal for downsizing, deregulation, and globalization. While the federal payroll may have shrunk, not so the cost of doing the public’s business, which has been outsourced to the point that “contractors have become a virtual fourth branch of government.”[5]

The spirit of laissez-faire has been hard to miss in the Katrina recovery. It permeated the multimillion-dollar debris removal contracts that were sole-sourced to politically connected corporations, which skimmed off the cream while dribbling out the whey to tiers of subcontractors. It has been even more salient in the so-called market-focused recovery taking place in New Orleans. The reconstruction effort did not start out that way. Early indications were that a posthurricane Galvestonism had seized control of the city’s destiny. While most city residents were still stranded in the diaspora, the principals of Nagin’s bnobc were meeting privately to map out a city that, whether they intended it or not, would probably end up being whiter and wealthier than before the storm. One of Nagin’s closest advisers and richest contributors, James Reiss, said as much in an unguarded comment to the Wall Street Journal a few weeks following Katrina: “Those who want to see this city rebuilt want to see it done in a completely different way: demographically, geographically and politically. . . . I’m not just speaking for myself here. The way we’ve been living is not going to happen again or we’re out.” The plan crafted by the developer-oriented Urban Land Institute (uli) for bnobc’s pivotal land-use committee seemed to reflect an exclusionist agenda.[6] uli recommended focusing recovery on areas that did not flood, so as to keep entire neighborhoods from turning into “jack-o-lantern” grids with occasional homes surrounded by blighted expanses. The unstated tenet of the plan was that residents should retreat to the natural levee where urban growth had been confined until modern hydrology drained the backswamp, while much of the rest of the city reverted to green space. Meanwhile, city officials should enforce a moratorium on building permits in the flooded areas.

To the tens of thousands of African Americans whose neighborhoods were being written off without their consent or even consultation with them, the uli plan summoned memories, not of Galveston in 1900, but of New Orleans in the 1870s, when the city’s white elite overthrew the problack state government and began dispossessing blacks of their fundamental rights. By the time the bnobc officially rolled out its proposal to a raucous meeting in a packed hotel ballroom downtown on January 11, 2006, Nagin had already disowned the project for reasons of political self-preservation. New Orleans’ most recent Creole mayor had embraced free-market individualism. Provide homeowners with relevant information, he said. Point out which areas are risky places to rebuild. Warn them that basic services—or affordable insurance—might not be available should they run that risk. But nonetheless allow homeowners to decide for themselves where and how to invest their bank loans, government grants, and insurance payouts. Devastated neighborhoods would sink or swim based on the choices of the people who lived and worked in them. That was the gist of Nagin’s market-focused strategy. It provided the city and its hard-hit utilities a clearer picture of which neighborhoods warranted the mammoth outlays necessary to rebuild New Orleans’s ruined infrastructure. Katrina’s waters had cracked five thousand miles of sewage collection pipes, corroded legions of gas mains, and transformed the water system into a municipal sieve (at one point it was losing eighty-five million gallons of water per day).[7]

As amendments to the Louisiana Constitution were passed in the late 1860s, rural organizers as well as urban activists took their place in the public sphere, pressing the campaign to increase former slaves’ access to rights and resources. Follow thread in Scott, “Road to Plessy v. Ferguson” >

Whether the mayor’s plan offered true freedom of choice or free-market anarchy, a messier way of reducing the city’s footprint than the ill-fated bnobc/uli plan, still is not clear eighteen months out from Katrina. There is an unmistakable Darwinism to Nagin’s market-driven recovery. For in the recovery process slouching forward on the Gulf Coast, only the fittest seem likely to survive: those with resources and determination. The resourceless are likely to fall—indeed, are falling—by the wayside. It is true that Katrina’s destructiveness was no respecter of class or race, but the same cannot be said of the recovery. Renters, some from the underclass (an awful but inescapable word for the truly disadvantaged) but most from the working poor and almost all African American, are in dire straits. Those who have not drifted back to town, doubling up with friends and relatives or squatting in abandoned shotgun houses, remain strewn across the American landscape. Most of the city’s rental property was devastated, and there has been scant urgency about restoring it, although a scarcity of affordable rentals is hindering the recovery of businesses starved for workers. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (hud) wants to tear down the city’s still-inhabitable low-rise developments, even though they were constructed in the days before shoddy building standards overtook public housing. The state’s solution to the rental shortage is to offer low-income tax credits to developers. Recipients of government-awarded low-income tax credits usually sell them to large corporations. The developers realize ready cash, and the corporations use the credits to lower their federal or state tax bill. However, the smart money is betting that most of the credits will go unused. Escalating insurance and construction costs are rendering the deals unworkable.[8]

People with resources—homeowners and proprietors of small businesses—are not faring well, either. The city has made a hash of posthurricane planning, and the invisible hand of the market is raising its middle finger. The view from Federal Emergency Management Agency (fema) trailers or the top floors of mold-remediated homes is clouded with uncertainty. Markets are all about coordinating expectations, but that is tough to do when the future is so opaque. Residents’ simple questions lack clear-cut answers: Will the neighbors down the street ever return and at least cut the grass? Should I take out a small business loan in the hope that my dry cleaning customers will move back next month—or next year? Today entire neighborhoods are struggling to prove their right to exist by showing they can rebuild. The odds are steep, and the struggle is, to quote organizers from the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (acorn), “grossly unfair.”[9]

And probably unworkable. As Thomas C. Schelling, the Nobel Prize–winning expert on complex bargaining, observed in December 2005: “There is no market solution to New Orleans.” Yet that is exactly what is being attempted in my adopted city, with the consequence that everything feels stuck-in-limbo. The iconic Lower Ninth Ward remains desolate; north of St. Claude Avenue, where a break in the Industrial Canal levee unleashed a minitsunami, one-quarter of all homes have been razed, and fewer than 3 percent of the former residents have applied for electrical permits. In the wealthier Lakeview neighborhood, the affluent are at least getting by. But in New Orleans East, where much of the aspirant and upwardly mobile black middle class once lived, the news is mixed. Electrical permits are up, but only 17.4 percent of the former population has applied for them. Those dismal statistics bear out a recent survey that found one-third of the city’s current population (a population half its pre-Katrina size) is contemplating leaving for good.[10]

The laissez-faire approach to recovery has spawned a laissez-faire attitude toward government, even among African Americans, who are usually among the staunchest supporters of activist government. Not only have city hall and Washington let them down, so has the welfare state built by the Kingfish and his progeny. Baton Rouge has allowed its image problems to paralyze planning efforts. “Washington doesn’t trust us with the money we need to recover, and we don’t trust each other,” observed one reporter in the waning days of a legislative battle to consolidate South Louisiana’s levee boards. So, with the $7.5 billion of federal Community Development Block Grant money awarded to the state by the federal government, the democratic governor Kathleen Blanco established an ostensibly fraud-proof recovery program called the Road Home and outsourced its administration to Beltway consultants who have turned it into a claim-proof one. Of the 100,000 Louisianians who applied for grants (the maximum allowable is $150,000 per applicant), only 532 had received funding as of mid-February 2007. (The pace picked up in March 2007.) Award letters were often riddled with errors; one couple in their nineties were mistakenly told they qualified for a paltry $550. “The Road Home program is a joke,” said the California congresswoman Maxine Waters during a February 2007 hearing.[11] New Orleanians nodded in agreement, feeling deep down that if this is the best government can do, maybe it should be doing less.

And yet there are signs the political landscape may be shifting. The policy agenda is starting to change, sometimes remarkably. Furthermore, the aftereffects of Katrina have triggered a social mobilization that may yet have far-reaching political consequences. Gloomy reports from the Gulf Coast regarding the sluggish recovery tell only part of the story and perhaps the less significant part. Much else is happening that bears close watching.

For one, there has been unforeseen turbulence in the policy arena. It has found expression in growing worries about infrastructure. Engineers and urban planners have known for years that the innards of many of our aging cities—their water systems and treatment plants, road and transit networks, gas and electricity systems, not to mention crumbling school buildings—are in need of triage. Four months before Katrina, a uli gathering had sounded the alarm about the consequences of disinvesting in urban infrastructure. The quadrennial report card issued by the American Society of Civil Engineers (asce), released around the same time, lowered the nation’s infrastructural grade from D+ to D. The number of hours Americans spend stalled in traffic has tripled since 1982, but until recently that discomfort failed to stimulate political interest in roads and bridges, except in the form of pork barrel earmarks.[12] The public may be awakening, however, thanks to 9/11 and Katrina, plus the global warming and megadisaster reportage that those tragedies have fostered. Especially in the hazard-prone coastal areas where more than half the current U.S. population lives, there is unease about disaster preparedness, especially about the susceptibility of interlocking infrastructure to cascading system failures. In November 2005 the keynote speaker at a “Lessons of Katrina” conference in the nation’s capital cautioned: “Katrina revealed that in other vital sectors, our critical infrastructure is vulnerable to disruption.”[13]

The collapse of New Orleans’s frail infrastructure not only placed an exclamation point after those warnings; it also underscored the social costs of neglecting the urban fabric. As the televised images streaming out of New Orleans immediately after Katrina made clear, the infrastructural failure of the levees—as well as the transit system, the power grid, and all the rest— fell with particular severity on the city’s dark-skinned poor. Now that Democrats control Congress and a presidential election is looming, we can expect more discourse concerning fiscal priorities. Why are we plowing money into Baghdad instead of Biloxi? Why are residents on the hard-hit Gulf Coast feeling caught between Iraq and a hard place? The Democratic senator James Webb of Virginia, the feisty conservative ex-marine who defeated George Allen in the 2006 election, phrased the question this way after Bush’s 2007 state of the union address: “How can we keep sending billions of dollars over to Iraq and not fund a really energetic effort to help places like New Orleans?” He called attention to the precariousness not merely of the nation’s economy but of its infrastructure. John Edwards, John Kerry’s 2004 running mate, did likewise when he chose the Lower Ninth Ward to announce his presidential candidacy. The post-Katrina moonscape of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast has become an a priori argument for reinvesting in our infrastructure. As an editorial writer for the New York Times put it in a one-year anniversary essay about Katrina: “The issue that really drives home the importance of building up our infrastructure is . . . Hurricane Katrina. The storm and its tragic aftermath exposed the flaws of our current system, and demonstrated in destructive detail why a better one is needed.”[14]

Then there is the matter of insurance or the pricey self-insurance that passes for coverage in today’s largely unregulated marketplace. The property and casualty field—which includes homeowner and fire and storm insurance—is the branch most in the news. Insurers have never been subject to federal oversight. In 1868 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that insurance regulation should be left to the states. Congress ratified that ruling in the McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945, which granted the insurance industry an antitrust exemption (the only industry other than major league baseball to enjoy one). The history of insurance is usually a tale of how external shocks (such as the Chicago and Boston fires of 1871 and 1872 and the deep depression of the 1890s) prompted consumer advocates in bellwether states to impose rate regulation.[15] In 1988 the insurance industry received a jolt when voters in California, its largest single market, mandated a large rollback in rates and banned the collusive sharing of actuarial data. Since 2000 demands have been growing in Congress to yank the insurance industry under federal control. The attack on the World Trade Center and the hyperactive hurricane season of 2004, which left Florida reeling, stepped up the political pressure. Yet no other shock has had quite the impact of Katrina—which, at $41 billion and counting, generated the largest single loss in the insurance industry’s history.What had been a deepening stream of ameliorative discontent before Katrina soon burst into a torrent of reformist anger after it.[16]

The anger is easy to understand. After Katrina property and casualty insurers, despite record profits ($44.2 billion in 2005, $63.7 billion in 2006), sought relief from their rate payers.Adjusters denied coverage where they could and low-balled claims where they could not. Companies jacked up premiums, raised deductibles, refused to insure against damage from wind and rain any longer, and dropped high-risk customers. Louisiana’s largest commercial insurer, Traveler’s Insurance, announced it was withdrawing from the state, until Bush’s recovery czar, Donald Powell, apparently jawboned it into staying. The parsimony of the insurance industry has brought forth litigation and cast a pall of gloom across the hurricane zone. Insurance is the lifeblood of real estate markets. Without coverage potential homeowners cannot get a mortgage, nor can investors in affordable housing make profitable use of tax credits while the cost of insurance remains high.[17]

Recent industry practices have sparked a legislative backlash—and in surprising places. In Florida, where rising insurance premiums threaten to choke off economic growth, Republican lawmakers enacted a prohibition on excess profits, with the strong endorsement of a conservative governor elected the previous November on a platform of lowering rates.[18] In Mississippi it was Trent Lott, the state’s once industry-friendly senior U.S. senator, who unfurled the banner of reform. Since the storm he has been wrangling with State Farm Insurance over its refusal to honor claims for the loss of his $400,000 beachfront house. In January 2007, hoping to defuse the political anger boiling up in Mississippi and to avert costly courtroom losses, the company agreed to a $130 million settlement with disgruntled policyholders (a federal judge, citing the need for more information, temporarily rejected the settlement, which is still under review as of September 2007). Nonetheless, Lott quickly reaffirmed his intention to cosponsor legislation with Democratic senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont, to end the industry’s antitrust exemption, causing State Farm to declare it would cease writing new policies in Mississippi. In early 2007, new demands seemed to arise every week from the floor of Congress to investigate insurers and bring them to heel.In March 2007 even U.S. Sen. Chris Dodd was berating one company for its “drive-by cancellations” in the New Orleans area, despite the heavy concentration of insurance companies in his home state of Connecticut. “What is happening here, it can happen all over the country,” he said. “This is a national issue.”[19]

It is too early to tell where the push to reform insurance will ultimately lead. One bill now in Congress would expand the National Flood Insurance Program to include multiple perils and would double the coverage policy limits. Another would establish a national catastrophe fund along the lines of the terrorism insurance program enacted after 9/11. The most likely outcome is a classic trade-off, giving industry a uniform and predictable federal regulatory environment in exchange for an agreement, to quote one industry observer, “to cover all perils in all parts of the country, or at the very least, reserve some number of low-cost subsidized policies for low-income policyholders.” Given the pressures building before Katrina to rein in the largely deregulated insurance industry, demands for federal intervention were bound to become insistent. But the devastating storm season of 2005 seems to have made them clamorous before their time.[20]

In Mississippi a grassroots campaign has demanded that legislators enact an “Insurance Bill of Rights.” The activism of ordinary people, many of them new to civic engagement, has epitomized post-Katrina politics.[21] In New Orleans the sluggish economic recovery and slow governmental response have called forth a veritable “low-intensity citizens’ revolution,” in the words of Adam Nossiter of the New York Times. uli’s shrink-the-footprint land plan landed like a bombshell in some neighborhoods. “It didn’t devastate us; it pissed us off,” said one resident of an area designated for green space. Almost as soon as it became clear that the onus for bringing back flooded neighborhoods would fall on individual homeowners, thousands of them queued up to apply for building permits. They formed new civic associations or breathed life into dormant ones. “I’m a child of the ‘70s, honey,” a small business owner told the New Orleans Times-Picayune. “We did disco. We didn’t do rallies. It’s kind of neat to get into this organizing thing.” And thousands began organizing with the doggedness of survivors convinced that helping neighbors was the best therapy available for working through personal trauma—to keep “from going crazy,” as one New Orleanian admitted.[22]

Neighborhood groups soon reconstituted themselves as planning committees. They set up resource centers to lend power saws and sanders; they created Web sites and electronic bulletin boards. Because the city’s public works division was understaffed and overwhelmed, local citizens improvised street signs and filled their own potholes. And if the craters were too big, they turned them into aquatic theme parks, replete with toy boats and fake flamingos. Aspects of such take-charge politics are historically rooted in the good-government activism of Uptown New Orleans, as Pamela Tyler has shown. Within weeks of the storm, several high-status white women, retracing the steps of their Progressive forebears, overthrew entrenched patronage machines by organizing successful drives to consolidate the region’s levee boards and abolish the city’s archaic tax assessment system. Yet the civic mobilization has been as much horizontal as vertical, energizing neighborhoods across lines of race and class. The city’s middle class, black and white, by dint of greater resources, is admittedly better organized. But former public housing residents, many of them still stranded in the diaspora, have launched lawsuits and have engaged in direct action to force the Housing Authority of New Orleans (hano) to reopen shuttered developments. In New Orleans East a community of Vietnamese refugees not only re-formed amazingly fast after Katrina, but halted the expansion of an encroaching landfill.[23]

Before Hurricane Katrina, Vietnamese Americans constituted less than 1.5 percent of the city’s population. Since Katrina, the small Vietnamese American community in eastern New Orleans has received significant press coverage due to its members’ high rate of return and the rapid rebuilding of their community. Follow thread in Leong, et al., “Vietnamese American Community in New Orleans East” >

Planning in post-Katrina New Orleans has been something of a “muddle.” Between the mayor and the city council, which hired its own planners, there has been a lot of toing and froing. The planning process really did not get started until a year after the storm, when it was placed under a nonprofit umbrella group (the Greater New Orleans Foundation) with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. A New Orleans Unified Plan has finally been woven from the threads of various neighborhood and district planning documents. Mayor Nagin has even hired a well-traveled recovery czar. The planning process has been messy, indeed, exhausting; so far the plan itself is really nothing more than a laundry list.[24] But it probably would not have advanced this far had residents not gotten ahead of the city and state. “We’re just taking matters into our own hands,” said one resident. “It’s just another post-Katrina coping mechanism.”[25]What blueprint eventually gets implemented may prove less important than the social capital generated by the civic mobilization itself. In the city of New Orleans, Katrina has produced a democratic moment that is still unfolding.

Some of the early stirrings began with professional organizers such as acorn. Its national headquarters has been based in New Orleans since 1978. Prior to Katrina the local paid-up membership totaled nine thousand families, mostly in low- to middle-income neighborhoods. The storm scattered staff and members and destroyed records, fates that befell most of the area’s nonprofit sector. acorn improvised new social and communications networks to connect displaced members. It cajoled banks and mortgage companies to extend the grace period for homeowners having difficulty meeting monthly notes. It transported dispersed residents to planning meetings in Baton Rouge or to congressional hearings in Washington to advocate for “the right of return.” Most critically, it picked up the gauntlet thrown down by city influentials who had warned residents to rebuild at their own risk. acorn’s organizers proceeded as though waging trench warfare with developers, power brokers, and their allies in government and academia, “who could only be trumped on the ground, house by house.” Abetting the scrub-and-clean campaign was the fact that much of its rank-and-file membership is working-class—individuals desperate to salvage the only asset they own, their homes. But acorn also received invaluable assistance from national partners, and affiliates in sister cities all along the evacuation trail.[26]

Activist groups from outside the area moved with comparable first-responder speed to fill the void created by faltering government. The New York–based Emergency Communities, founded for the occasion by dreadlocked hippies who reasoned that their skill at operating outdoor rock concert kitchens had utility in the disaster area, swiftly set up tents in a shopping center parking lot in devastated St. Bernard Parish. Within three months, their motley coalition—a veritable “mash unit but without the uniforms”—was serving two thousand meals a day and offering free tetanus shots and Reiki massages.[27] The Common Ground Collective (more popularly known as Common Ground Relief) formed in response to distress calls from the former Black Panther Malik Rahim. Within a matter of weeks Rahim and two organizers from Austin, Texas, saw their do-it-yourself start-up operation balloon from three to sixty activists, including self-conscious descendants of the Industrial Workers of the World (iww) Wobblies. They recruited medics, carpenters, and computer technicians. They established medical clinics, distribution centers, and ad hoc house-gutting services. Returning residents to the devastated Ninth Ward were fed free breakfasts, provided free legal services, and given access to phone and Internet services. Common Ground Relief set out not merely to save a city, but to build alternative social structures—“without expecting the permission of the government, and often in defiance of it.” Its most enduring impact, though, may prove to be its success in recruiting outside volunteers—more than ten thousand from every state in the Union and Washington, D.C., by their reckoning. Those volunteers have mainly been white middle-class college students attracted to such outreach events as Alternative Spring Break and Thanksgiving Road Trip for Relief.[28]

But for every radical novitiate evangelized by dedicated anarchists and global justice activists, there have been ten apolitical volunteers who have been drawn to New Orleans by faith-based organizations, professional gatherings, or the simple call of conscience. There have been Barefoot Doctors, Mondo Bizzaro Productions, a multidisciplinary arts group, and the Rainbow Family of Living Light. Faith-based volunteers stand out. They come as Bible study groups, sleeping in rvs and tents, chainsaw-toting pilgrims on missions of earthly salvation. Katrina recovery is “the biggest domestic relief effort we’ve ever faced,” said a spokesman for the United Methodist Committee on Relief. The newly elected president of the 16 million-member Southern Baptist Convention, shaken by a tour of Lakeview and the Lower Ninth (“It looks like something after a nuclear bomb”), pledged to get the word out to the autonomous churches constituting his confederation. “I have access to the Baptist press, and I’m going to use that,” he told the Times-Picayune six weeks before Katrina’s first anniversary. “I have a weekly address, and I’ll use that. I’ll be speaking all over the nation for the next six months, and I do pledge and promise to make New Orleans’s neighborhoods a point of great emphasis for our ministry.”[29]

His promise and similar pledges by like-minded religious leaders have not been empty. Thousands of faith-based volunteers have been arriving in the Katrina zone every month to spend a week or two, but sometimes longer, pulling Sheetrock. One Iowa volunteer drawn to New Orleans by the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana gave up her job in the Des Moines statehouse in order to help manage volunteer operations on the ground. Samaritans have usually returned home transformed by the house-gutting experience. “Now that we are back in Michigan,” wrote an Ann Arbor volunteer with the Catholic Charities program Operation Helping Hand, “we are urging others to band together, travel to New Orleans and help as well.”[30]It is hard to haul curbside the sodden contents of another family’s life—its broken dishes and waterlogged photo albums, their snapshots dissolved into tie-dyed artwork—without stretching the boundaries of one’s moral obligation.

And not least among the volunteers have been the conventioneers—the librarians and realtors—who traveled to New Orleans to attend professional meetings but took time out to clean and restock libraries, plant trees in City Park, or repair houses rotting after “the storm-that-won’t-end,” as a contributor to the Washington Post put it. Katrina has even changed the face of so-called voluntourism, a nascent movement that champions Peace Corps–type holidays. Until the 2005 storm season, Third World venues were the destination of choice for vacationing Samaritans. Since Katrina voluntourists have been heading for the stricken Gulf Coast in mounting numbers.[31]

But is volunteering enough? Can the methods of a nineteenth-century barn raising drag a twenty-first-century disaster area from the mud and the muck? Even prior to Katrina, as the cutbacks in social spending sank in, mainstream volunteer organizations were starting to question whether “compassionate conservatism” could do everything being claimed in its name. Or as Sara Mosle has put it: “The problem with volunteering isn’t with volunteering, but with what we’re asking it to do.”[32] It is a realization that has started to dawn on many outside volunteers. You only have to spend a backbreaking week pulling drywall and mucking out houses to appreciate that altruism alone cannot restore electrical grids or fix broken pipes, let alone solve the myriad insurance and financial problems that currently stymie the post-Katrina recovery. You only have to strip one or two houses down to their studs before asking, shouldn’t government be playing more of a hands-on role in the recovery? Those conversations have already started across backyard fences. It is more than likely that an entire generation of young activists will look back on their volunteer service in the Katrina zone as a life-changing experience, as a time that shaped their political values for years to come. Every generation has defining memories. For mine it was the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the civil rights movement, and the Vietnam War. For this generation it may turn out to be 9/11 and Katrina—and maybe more so Katrina, whose aftereffects may become more iconic, at least of the failure of government, than the toppling of the twin towers.

We have probably gone too far down the road of states’ rights federalism for some sort of New Deal–type agency such as the Tennessee Valley Authority to arise any time soon. The need for such a regional entity, with the capacity to coordinate relief and recovery activity across multiple levels of government and between public and private actors, has never been more apparent than now. All the same, the pendulum does seem to be swinging back toward the public sphere. When conservative southern Republican politicians start intervening in the insurance market or call for regulating outsourcing (as the governor of Florida has recently done), it is a sign the country is overdue for a conversation about the role of government.[33] Heaped atop an issues agenda already groaning beneath the weight of unfinished business—immigration, affordable health care, and Social Security (the “third rail” of American politics)—the looming insurance and infrastructure crises alone could easily speed up a reform timetable long stalled by laissez-faire ideology. Now that the insurance industry has been put on the defensive, it is becoming easier to imagine meaningful health care reform eventually being enacted in Washington.

Whether Katrina proves to be one of those detonating events that every so often nudges Americans back toward activist government is hard to divine. Historians are notoriously bad soothsayers. But careful students of the American past cannot help but be struck by the similarities between contemporary politics and early Progressivism in all of its contradictoriness and incoherence. A century ago ordinary citizens felt vulnerable in the face of big industry and finance capitalism. Many voters abandoned established parties (or, in the South, were disfranchised), beginning a long march toward the political dealignment that still characterizes the current era. And into that void rushed a plethora of extraparty interest groups demanding that monopolies be reined in or pressing the claims of the urban poor while challenging the myth of autonomous economic man.[34] Today there is deep-seated unease about globalization, offshoring, and the corrupting influence of lobbyists. ceos have lost their charmed immunity. Meanwhile, new forms of communication akin to the muckraking journalism of yesteryear have given ordinary citizens not only information but also the power to disseminate it. Ubiquitous Internet blogs are multiplying opportunities for building social networks and for organizing political communities in ways scarcely imaginable two decades ago. True, the ceaseless drumbeat from the Right over the years about government being part of the problem, not the solution, has left a residue of skepticism toward the public order. But destructive events such as Katrina cannot help but change the dynamic. They have already done so.[35]

I wish I could say New Orleans will benefit from a rebirth of governmental activism. Doubtless the city will recover—after a fashion. But large swaths of it probably will remain in limbo for years to come. Resilient cities that rebound from disaster almost always benefit from vibrant economies. But ours is in shambles. According to one outside economist, “This is the first time in U.S. history where a city has sat dormant for almost a year.” This comes on the heels of an economic decline that has been underway for decades. Even the port that built the city is losing ground to Houston and Mobile.[36]The only economic engine with anything left in its tank is the hospitality industry, and too much of that is fueled by a Third World wage structure. Neighborhoods that once produced a distinctive musical culture are likely gone forever. Some of our vernacular culture will survive because of the attachment to place this city has always commanded from residents and visitors. Still, the future is not rosy in the Big Easy.

Charles Beard and Frederick Jackson Turner, two giants of Progressive historiography, understood that “if a new or heterodox idea is worth anything at all it is worth a forceful overstatement,” to quote Richard Hofstadter.[37] I hope my zeal to find a usable past has not tempted me into Progressive hyperbole, but time will have to be the judge of that.

The problem with writing instant history is that there is always a new instance. I derived this article from a talk that tried to encapsulate a moment in the post-Katrina recovery that I was sure fell somewhere in the middle of the story. It is now clear that the narrative is stuck near the beginning, and that it will require at least another ten years for the saga to reach its conclusion. Even so, little has happened since the Mobile conference in March 2007 to change my mind about Katrina’s political aftereffects. It is safe to say that there was more national news coverage of the Minneapolis bridge collapse in August 2007 because of the heightened public concern about the state of national infrastructure engendered by the levee failures in New Orleans. Moreover, there is continued movement toward the enactment of a national catastrophe fund, an emerging debate over so-called catastrophe bonds as a market-focused way of spreading post-Katrina risk, and investigations by both Congress and the courts into allegations that insurers shifted their own damage claim liabilities onto the federal flood insurance program. The Gulf Coast, particularly New Orleans, continues to attract volunteers, except now they are coming to stay, not for a week, but for a year. Two new developments are worth noting. Since March, the troubled Road Home program has turned some kind of corner, closing on more than sixty-four thousand applications as of mid-October 2007, but now faces a possible $6 billion shortfall. The other development has surprised me: the reemergence of the poverty debate. There may be no better measure of Katrina’s power to unleash ethical energy than the return of that subject to the national agenda.

Katrina, in short, continues to cast a long shadow over national politics. Paul Krugman recognized as much in a New York Times column, “Katrina All the Time.” It is one of the most frequently e-mailed of all of his opinion pieces. He wrote, “Future historians will, without doubt, see Katrina as a turning point. The question is whether it will be seen as the moment when America remembered the importance of good government, or the moment when neglect and obliviousness to the needs of others became the new American way.”[38]

I remain guardedly optimistic that Katrina marks a turn toward the former.

I would like to thank James Boyden, Steven Hahn, Lance Hill, Edward Linenthal, Clarence Mohr, Rebecca Scott, and Michael Wayne for their perceptive comments. Susan Armeny and Donna Drucker also deserve thanks for economizing the prose and clarifying the argument. The responsibility for the argument—and the errors—is mine alone.

[1] For a helpful survey of narratives of resilience and civic renewal, see Laurence Vale and Thomas J. Campanella, eds., The Resilient City: How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster (New York, 2004), esp. their introduction and Edward T. Linenthal, “‘The Predicament of Aftermath’: Oklahoma City and September 11,” 55–76; and Kevin Rozario, “Making Progress: Disaster Narratives and the Art of Optimism in Modern America,” 27–54. See also Philip Fradkin, The Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906 (Berkeley, 2005), 310–12.

[2] Elisabeth Bumiller, “Bush Pledges Federal Role in Rebuilding Gulf Coast,” New York Times, Sept. 16, 2005, p. A1.

[3] On San Francisco, see Fradkin, Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906, 5–6, 14, 18–20, 305–38; and Walton Bean, Boss Ruef’s San Francisco: The Story of the Union Labor Party, Big Business, and the Graft Prosecution (Berkeley, 1952), vii, 119–27. On Galveston, see Patricia Bellis Bixel and Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Galveston and the 1900 Storm: Catastrophe and Catalyst (Austin, 2000), 89–95; and Bradley Robert Rice, Progressive Cities: The Commission Government Movement in America, 1901–1920 (Austin, 1977), 19–33.

[4] John Barry, Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America (New York, 1997), 399–422; Coleman Warner, “Locals Key to N.O. Rebirth,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 20, 2006, “Metro” section, p. 1. On the number of people displaced by Katrina, see Peter Grier, “The Great Katrina Migration,” Christian Science Monitor, Sept. 12, 2005, http://www.csmonitor.com/2005/0912/p01s01-ussc.html?s=t5. On the dust bowl, see Timothy Egan, The Worst Hard Time (Boston, 2006), 9. The latest estimate of Katrina damages is $125 billion. See Eileen Alt Powell, “Katrina Damage Estimates Upped to $125B,” Sept. 9, 2007, Breitbart.com, http://www.breitbart.com/article.php?id=D8CGRP0O0&show_article=1.

[5] See Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., The Cycles of American History (Boston, 1986), 25–27. On the Clintonian origins of welfare reform and Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere (hope vi), the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (hud) program for replacing public housing with so-called mixed-income developments, see Jason DeParle, American Dream: Three Women, Ten Kids, and a Nation’s Drive to End Welfare (New York, 2004); Scott Shane and Ron Nixon, “In Washington, Contractors Take on Biggest Role Ever,” New York Times, Feb. 4, 2007, p. A1.

[6] Christopher Cooper, “In Katrina’s Wake: Old-Line Families Escape Worst of Flood and Plot the Future,” Wall Street Journal, Sept. 8, 2005, p. A1. For an insider account of the early planning effort, see Jonathan Barnett and John Beckman, “Reconstructing New Orleans: A Progress Report,” in Rebuilding Urban Places after Disaster: Lessons from Katrina, ed. Eugenie L. Birch and Susan M. Wachter (Philadelphia, 2006), 288–304.

[7] Michelle Krupa, “Sewer Systems Decimated; Storm Damage Said Close to $1 Billion,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, April 28, 2006, p. 1; and Michelle Krupa, “Hard-Hit S&WB Swamped in Red Ink; $50 Million Tab Tied to City’s Water Leaks,” ibid., June 10, 2006, p. 1.

[8] Residents are suing hud and the Housing Authority of New Orleans (hano), and the case is slated for trial. Gwen Filosa, “Public Housing Dispute Headed for Trial; Judge Says It’s Only Way to Resolve Issues,” ibid., Feb. 9, 2007, p. 1. David Hammer, “Relief Far Off for Louisiana Rental Owners; Their Road Home Paved with Red Tape,” ibid., Jan. 4, 2007, p. 1; Rebecca Mowbray, “Low-Cost Housing Answers Sought by Group; La. Agency Meets with Developer,” ibid., money section, Feb. 3, 2007, p. 1.

[9] Wade Rathke and Beulah Laboistrie, “The Role of Local Organizing: House-to-House with Boots on the Ground,” in There Is No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster: Race, Class, and Hurricane Katrina, ed. Chester Hartman and Gregory D. Squires (New York, 2006), 268.

[10] Peter G. Gosselin, “On Their Own in Battered New Orleans,” Los Angeles Times, Dec. 4, 2005, http://www.latimes.com/business/la-na-orleansrisk4dec04,0,2773341.story; Gordon Russell and Richard Russell, “Patchy Progress Plays Out in N.O.,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, Dec. 31, 2006, p. 1; John Pope, “1/3 in Orleans, Jeff Consider Leaving; Survey Examines Post-K Quality of Life,” ibid., Nov. 29, 2006, p. 1. See also Shalia Dewan, “New Orleans’s New Setback: Fed-Up Residents Are Giving Up,” New York Times, Feb. 15, 2007, p. A1.

[11] Jed Horne, Breach of Faith: Hurricane Katrina and the Near Death of a Great American City (New York, 2006), 351. Jeffrey Meitrodt, “State Blasts Road Home Firm; But Top Exec Defends icf’s Performance,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, Dec. 24, 2006, p. 1; Coleman Warner, “Road Home Promises, But Family Still Waits,” ibid., Dec. 29, 2006, p. 1; Bill Walsh, “Hearing Blasts La.’s Housing Recovery: Road Home ‘A Joke,’ Congresswoman Says,” ibid., Feb. 7, 2007, p. 1.

[12] Michael Pawlukiewicz, “Financing the Urban Infrastructure,” Washington: Urban Land Institute, April 7–8, 2005 (in Lawrence N. Powell’s possession). For the American Society of Civil Engineers (asce) report card, see asce, “Small Steps for Big Improvements in America’s Infrastructure,” Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, http://www.infrastructurereportcard.org.

[13] C. J. Crowley, “Introduction to the Morning Keynote Address,” paper delivered at the conference “Lessons of Katrina: Critical Infrastructure, Preparedness, and Homeland Security,” Washington, D.C., Center for American Progress, Nov. 17, 2005, p. 5, http://www.americanprogress.org/events/2005/11/b593305ct1573973.html; Dean E. Murphy, “Storms Put Focus on Other Disasters in Waiting,” New York Times, Nov. 15, 2005, p. A24; Mary C. Cormerio, Disaster Hits Home: New Policy for Urban Housing Recovery (Berkeley, 1998), 2–5.

[14] Nicolai Ouroussoff, “How the City Sank,” New York Times, Oct. 9, 2005, sec. 2, p. 1. Charles D’Aprix, letter to the editor, ibid., Oct. 16, 2005, sec. 2, p. 5; Kathy Kiely, “Webb Would Defund Rebuilding Iraq,” USA Today, Jan. 21, 2007, p. 4A; Adam Nossiter, “New Orleans Is Exhibit A as Edwards Opens His Presidential Campaign,” New York Times, March 1, 2007, p. A1; Nicholas Kulish, “Things Fall Apart: Fixing America’s Crumbling Infrastructure,” ibid., Aug. 23, 2006, http://select.nytimes.com/2006/08/23/opinion/23talking-points.html.

[15]Paul v. State of Virginia, 75 U.S. 168 (1868); McCarran-Ferguson Act, 15 U.S.C. sec. 1011 (1945). On the insurance industry and its early regulation, see Morton Keller, The Life Insurance Enterprise, 1885–1910: A Study in the Limits of Corporate Power (Cambridge, Mass., 1963), 194–242; and H. Roger Grant, Insurance Reform: Consumer Action in the Progressive Era (Ames, 1979). See also Robert H. Jerry II and Steven E. Roberts, “Regulating the Business of Insurance: Federalism in an Age of Risk,” Wake Forest Law Review, 41 (Fall 2006), 835–78; Etti G. Baranoff and Dalit Baranoff, “Trends in Insurance Regulation,” Review of Business, 24 (Fall 2003), 11–20; and Marc Schneiberg, “Combining New Institutionalisms: Explaining Institutional Change in American Property Insurance,” Sociological Forum, 20 (March 2005), 93–136.

[16] On Proposition 103 in California, see Samuel H. Szewczk and Raj Varma, “The Effect of Proposition 103 on Insurers: Evidence from the Capital Market,” Journal of Risk and Insurance, 57 (Dec. 1990), 671–81. For the Katrina loss figures, see Insurance Information Institute, “Defraying the Economic Costs of Disasters,” http://www.economicinsurancefacts.org/economics/disasters/hurricanes/. On the shift in the political terrain, see Barbara O’Brien, “The Insurance Industry Meets Katrina,” online posting, Feb. 1, 2007, dmiblog: Politics, Policy, and the American Dream, discussion list, http://www.dmiblog.net/archives/2007/02/the_insurance_industry_meets_k.html.

[17] Kathy Chu, “Insurance Rates Still Feel Katrina’s Storm Winds,” USA Today, April 20, 2007, p. 3B. See, for example, Joseph B. Treaster, “State Farm Settles Katrina Claims in Mississippi,” New York Times, Jan. 23, 2007, p. C1; Rebecca Mowbray, “Travelers Won’t Desert Commercial Insurance: It Now Plans to Retain 60% of Its Customers in South Louisiana,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, Jan. 5, 2007, p. 1; Ed Anderson, “Insurance Reform Called Key to the Future; Panel’s Chair Warns of Crippled Recovery,” ibid., Jan. 18, 2007, p. 2; Bruce Alpert, “Congress Looks at Bills on Post-Hurricane Insurance; Multiple-Peril Policies, Anti-Trust Rule Weighed,” ibid., Feb. 16, 2007, p. 3.

[18] Abby Goodnough, “Florida Acts to Lower Home Insurance Cost,” New York Times, Jan. 23, 2007, p. A12; Peter Whoriskey, “Florida’s Big Hurricane Gamble,” Washington Post, Feb. 20, 2007 p. A2; Rebecca Mowbray, “Insurers Rain on Sunshine State’s Reforms,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, “Metro” section, Jan. 28, 2007, p. 1.

[19] Peter G. Gosselin, “State Farm Puts Brakes on Mississippi Policies,” Los Angeles Times, Feb. 15, 2007, p. 28A; Joseph B. Treaster, “Judge Puts Settlement on Katrina in Question,” New York Times, Jan. 27, 2007, p. C1; Maria Reccio, “Lott, Taylor Are Not Giving Up,” Biloxi Sun Herald, Jan. 25, 2007, http://www.sunherald.com/mld/sunherald/business/industries/insurance/16540110.htm; Arthur D. Postal, “Sen. Lott’s Election Brings Fear to P-C Sector,” National Underwriter P & C, Nov. 20, 2006, p. 37. Rebecca Mowbray, “Allstate Cancellations Blasted,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, money section, March 10, 2007, p. 1.

[20] For a Progressive period analogue, see Keller, Life Insurance Enterprise, 227–44. Marcy Gordon, “Lawmakers Seek National Catastrophe Fund,” Washington Post, March 15, 2007, available at Lexis-Nexis. After 9/11, a $100 billion taxpayer-financed bailout cushioned the blow to the insurance industry’s reserves. Scott Lindlaw, “Bush Signs Bill Protecting Insurance Industry from Future Attacks,” Austin Daily Texan, Nov. 27, 2002, http://www.dailytexanonline.com/news/2002/11/27/; R. J. Lehmann, “Perspectives: Can Deregulation Partisans and Consumer Activists Actually Find Common Ground?,” Best Wire, Feb. 5, 2007, http://www.agents4change.net/page.asp?g=FSRAC&content=BestWire_Perspectives_2_5_07&parent=FSRAC; Bruce Alpert, “Congress Looks at Bills on Post-Hurricane Insurance,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, Feb. 16, 2007, p. 3. On the widening gap between citizens and Alabama’s conservative officialdom, see Dan Murtaugh, “Poll: Government Should Do More to Regulate Insurance,” Mobile Press-Register, March 4, 2007, p. A1. On Louisiana’s cozying up to the insurance industry, see Rebecca Mowbray, “Business Group Urges Insurance Changes,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, Jan. 6, 2007, p. 1; Rebecca Mowbray, “Blanco Traveling to Woo Insurers to Louisiana,” ibid., Jan. 29, 2007, p. 1; and Ed Anderson, “Blanco Opts against Special Session on Insurance Issues,” ibid., Feb. 10, 2007, p. 3.

[21] I am indebted to my colleague Marline Otte’s important documentary-in-progress for this observation.

[22] Adam Nossiter, “Bit by Bit, Some Outlines Emerge for a Shaken New Orleans,” New York Times, Aug. 27, 2006, p. A1. See also Anita Lee, “Moving Mountains: Homeowner Tackles Insurance Bill of Rights,” Biloxi Sun Herald, Jan. 5, 2007, p. A1; Coleman Warner, “Locals Not Waiting to Be Told What to Do,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, March 13, 2006, p. 1; and Michelle Krupa, “Katrina Generates Wave of Activism,” ibid., Aug. 27, 2006, p. 1.

[23] Lynne Jensen, “Dripping, with Satire,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, “Metro” section, April 17, 2006, p. 1; Gwen Filosa, “Public Housing Dispute Headed to Trial,” ibid., national section, Feb. 9, 2007, p. 1; Gwen Filosa, “Ejected Public Housing Residents Return to C. J. Peete,” ibid., “Metro” section, Feb. 11, 2007, p. 1; Bruce Eggler, “deq Will Abide by Landfill Decision,” ibid., national section, July 26, 2006, p. 1. See also Pamela Tyler, “The Post-Katrina, Semiseparate World of Gender Politics,” Journal of American History, 94 (Dec. 2007), 780–88; and Karen J. Leong et al., “Resilient History and the Rebuilding of a Community: The Vietnamese American Community in New Orleans East,” ibid., 770–79.

[24] Gordon Russell, “On Their Own,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, Aug. 27, 2006, p. 1; Coleman Warner, “Recovery Planning Pact Signed,” ibid., “Metro” section, Aug. 29, 2006, p. 1; Michelle Krupa, “N.O. Plans Leaving Drawing Board,” ibid., Jan. 7, 2007, p. 1; Coleman Warner, “Rebuilding Sessions Casting Wide Net,” ibid., national section, Dec. 1, 2006, p. 1; “Editorial: Nearing a Plan at Last,” ibid., “Metro-Editorial” section, Jan. 23, 2007, p. 4; Bruce Eggler, “N.O. Recovery Plan Called a Muddle,” ibid., national section, March 6, 2007, p. 1. See also Kristina Shevory, “A New Orleans Neighborhood Rebuilds,”New York Times, real estate section, Feb. 25, 2007, p. 1.

[25] Coleman Warner, “Signs of the Times,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, April 9, 2006, p. 1.

[26] Rathke and Laboistrie, “Role of Local Organizing,” 266. The national partners are iaf (Industrial Areas Foundation) and pico (People Improving Communities through Organizing). Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (acorn) is not without its critics, on both right and left. See Rotten acorn: America’s Bad Seed (Washington, Employment Policies Institute, July 2006), http://www.rottenacorn.com/downloads/060728_badSeed.pdf; and Jay Arena, “A Local 100 Organizer Remembers,” To-Gather, Feb. 19, 2001, pp. 1–2.

[27] Eric Patel, “Hard Work in the Big Easy,” Washington Post, travel section, July 9, 2006, p. 1.

[28] Common Ground Relief expects the recruits to return to their home communities as “antiracist allies,” and several probably will. See Sue Hildebrand, Scott Crow, and Lisa Fithian, “Common Ground Relief,” in What Lies Beneath: Katrina, Race, and the State of the Nation, ed. South End Press Collective (Cambridge, Mass., 2007), 80–98, esp. 86 and 92; and Jordan Flaherty, “Corporate Reconstruction and Grassroots Resistance,” ibid., 100–119. See also Zeke Rediker, “From the Ground Up: Rebuilding New Orleans with the Radical Common Ground Collective,” Kitsch Magazine (no. 3, Spring 2007), http://www.kitschmag.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=164&Itemid=26; Gwen Filosa, “Lower Ninth Ward Activists Chase Away Bulldozer Crew,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, “Metro” section, Jan. 6, 2006, p. 1; and “Activists Plead for Help Gutting Homes,” ibid., Oct. 12, 2006, p. 1.

[29] Frank Etheridge, “On the Ground,” New Orleans Gambit Weekly, Dec. 20, 2005, p. 24; Jacqueline L. Salmon, “By the Thousands, Faithful Toil to Resurrect Gulf States,” Washington Post, Feb. 5, 2006, p. A1; Bruce Nolan, “Faith-Based Groups Focus on Housing as They Shift into a New Phase of Katrina Recovery,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, June 11, 2006, p. 1. Bruce Nolan, “Baptist Leader Pledges Relief,” ibid., July 18, 2006, p. 1. Southern Baptists have gutted 12,000 houses in Mississippi alone and repaired another 3,000 homes. Leslie Eaton and Stephanie Strom, “Volunteer Group Lags in Replacing Gulf House,” New York Times, Feb. 22, 2007, p. A1.

[30] Krupa, “Katrina Generates Wave of Activism,” p. 1; and Ernestine R. McGlynn, “Volunteers Dig out Homes, Return Changed,” ibid., “Metro-Editorial” section, Aug. 1, 2006, p. 7.

[31] Patel, “Hard Work in the Big Easy.” See also Michelle Krupa, “Green Revolution,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, June 8, 2006, p. 1; and Tania Tetlow, “Stricken Libraries Bear Witness to Disaster,” ibid., “Metro-editorial” section, June 22, 2006, p. 7; Linton Weeks, “New Orleans Working Vacations Catching On,” Washington Post, March 15, 2006, p. A3. For a thumbnail sketch of voluntourism, see Voluntourism International, Voluntourism, http://www.voluntourism.org/.

[32] Sara Mosle, “The Vanity of Volunteerism,” New York Times Magazine, July 2, 2000, p. 22.

[33] Eugiene L. Birch and Susan M. Wachter, “Introduction: Rebuilding Urban Places after Disaster,” in Rebuilding Urban Places after Disaster, ed. Birch and Wachter, 8–10; Joe Follick, “Gov. Crist Seeks More Outsourcing Oversight,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, Feb. 22, 2007, p. A1.

[34] Richard P. McCormick, “The Discovery That Business Corrupts Politics: A Reappraisal of the Origins of Progressivism,” American Historical Review, 86 (April 1981), 247–74. For a critique of the historiography on Progressivism, see the still indispensable essay by Daniel T. Rodgers,“In Search of Progressivism,” Reviews in American History, 10 (Dec. 1982), 113–32.

[35] On the argument for regional governance, see Gar Alperovitz, “California Split,” New York Times, Feb. 10, 2007, p. A15.

[36] Rebecca Mowbray, “Wounded N.O. Economy Remains in Coma,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, national section, Aug. 25, 2006, p. 1. See also Jacquetta White, “Katrina’s Toll on Business Tallied,” ibid., money section, March 9, 2007, p. 1; and Jacquetta White, “Missing the Boat,” ibid., April 8, 2007, p. 1.

[37] Richard Hofstadter, The Progressive Historians: Turner, Beard, Parrington (New York, 1968), 120.

[38] Paul Krugman, “Katrina All the Time,” New York Times, Aug. 31, 2007, p. A21.