Boredom is not the worst result of traditional coverage-oriented surveys. It is only the most obvious result.

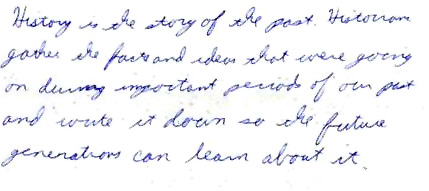

Consider this college sophomore’s definition of “history”:

(Text in image: "History is the story of the past. Historians gather the facts and ideas that were going on during important periods of our past and write it down so the future generations can learn about it.")

To academic historians, such an understanding of history seems terribly naïve. It assumes there is only one story about the past. It pictures the historian’s task to be a simple one in which facts are located, lined up, and written down. This student’s misconceptions about history are typical of what Bob Bain observed of high school students’ “static, formulaic vision of history. The past is filled with facts, historians retrieve those facts, students memorize the facts and all of this somehow improves the present.” (in Peter N. Stearns, Peter Seixas, and Sam Wineburg, eds., Teaching and Learning in National and International Contexts (New York University Press, 2000). For the students enrolled in our surveys, history is less a “discipline” than it is a “subject,” differing from other subjects only in the particular facts that are covered.

What this means is that it is possible for survey teachers to be entirely successful at holding students’ interest over the length of a term—delivering the most magnificent lectures, inspiring a tremendous thirst to know more about historical subjects, even providing a wonderful model of what it means to “think historically,”—and yet remain oblivious to a considerable problem. If one is a gifted lecturer, it is possible by this very fact to be teaching, unintentionally, of course, the most regrettable misconceptions about what it means to think well about the past. As Red Auerbach once pointed out, it’s not what you say; it’s what they hear.

For example, what does a coverage survey convey about what it means to be “good” at history? In traditional surveys, it means recalling other people’s knowledge, which teacher and textbook have covered for students. In this case, to “cover” means “to go the distance of.” But “to cover” also means “to conceal” or “to cover up.” When history gets covered, what gets covered up are the very thinking skills that make historians good at history, and that students need to navigate their way through a parlous world.

In coverage surveys, class activities and assessments make history out to be a subject, hiding the fact that it is also a discipline. There is little or no opportunity for students to struggle with the art of historical inquiry, as this is done for them in lectures and textbooks that conceal the subjective nature of historical interpretation. Instead of engaging the past as historians do, discussing events in terms of debates over evidence and point of view, students encounter history as a facade of static, objectified, and voiceless accounts of the past. Not only is there little or no opportunity to interpret historical evidence, there is also no chance for multiple opportunities to build skills in historical analysis and argumentation and no scope for raising the most important question of all: What does the past mean? When history is presented in this way, as a mass of facts to be absorbed by sponge-like minds, who can wonder at reports that the survey leaves most students feeling confused and unable to reconstruct what they have just studied. For the best students, taking the survey is like trying to get a drink from a fire hydrant. For most, it leaves entirely the wrong idea about what history really is.

College professors may not be responsible for creating fundamental misconceptions about history, but we ought not to dodge our responsibility for failing to recognize, prepare for, and correct them. Indeed, the coverage survey’s responsibility for perpetuating misconceptions about history is so grave that we may need to admit that “misconception” is the wrong term for describing our students’ naïve beliefs about the nature of historical mindedness. After all, “misconceptions” are misunderstandings of concepts that have been formally taught to students. If a student has never been introduced properly to history as an epistemic discipline, then her beliefs about history reflect not a “misconception” but an “alternate frame of reference,” an autonomous conceptualization of the world based on her experience of it, which included coverage-based history courses. (Ola Halldén, “On the Paradox of Understanding History in an Educational Setting,” in Gaea Leinhardt, Isabel L. Beck, and Catherine Stainton, Teaching and Learning in History (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1994, p. 29.) Like Pogo said, “We have met the enemy, and it is us.”