|

Connecting to the Public: Using New Media to Engage Students in the Iterative Process of History Cecila O├şLeary As a cultural historian in an interdisciplinary department├│New Humanities for Social Justice├│at California State University, Monterey Bay, I continually grapple with what to emphasize in the one required history course for majors. At the Visible Knowledge Project Summer Institute in 2000, colleagues encouraged me to foreground the digital turn in history by linking new media with my longtime goal of inspiring students to become citizen historians.

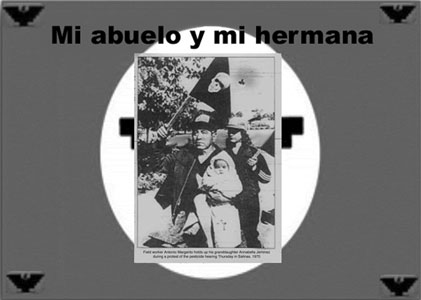

This collage is the logo for Cecilia O’Leary’s course Multicultural History in the New Media Classroom at California State University, Monterey Bay. O’Leary’s student Yael Maayani designed the collage in 2000, using the artist Rini Templeton’s drawings. Templeton created the drawings between 1974 and 1986 for public use by activists in Mexico and the United States. Courtesy Betita Martinez. Citizen historians understand their right both to learn and to make history: they assume responsibility for contributing to the ongoing project of uncovering the diversity of our past and expressing that historical knowledge in a public forum. In Multicultural History in the New Media Classroom, I combine traditional approaches to reading and writing with an assignment that requires students to present their research projects in new-media forms. Students are involved in authentic tasks├│that is, the kind of work undertaken by historians, including complex inquiry and analytical thinking├│and accept accountability for the ├Čpublic dimension of academic knowledge.├«41 Self-consciously applying the scholarship of teaching and learning to evaluate my course and its outcomes, I have been able to document how digital history assignments helped my students develop two key historical-thinking skills. First, my students developed the ability to place themselves in history; this is an especially significant achievement since many of them are working-class and first-generation college students from migrant families who work in the fields surrounding my university. Although such students are too often seen only as hampered by deficits associated with inadequate preparation, my students in fact bring critical assets to the classroom├│family and community experiences that help them write narratives of social change and move those stories from the margins into the mainstream of history.42 Second, my students discovered the iterative nature of historical knowledge├│that is, the need for historians to revise their findings in light of the knowledge they discover in the process of research and presentation. In their own efforts to stitch together the patchwork of evidence they have collected, they learned how to refocus, rewrite, and rethink the stories they tell.43 Making digital histories presents students with daunting technical challenges. But these new-media narratives also foster student learning in large part because of the real stakes in presenting history to a wider audience. As deadlines approach, students try to fill holes in their research and to comprehend whether new information strengthens their original interpretation or raises new directions. The very act of going back over the evidence they have collected involves them in the pattern of recursive iterations that ├Čseparates good historians from not very good historians.├«44 The particular historical period or pedagogical approach I take varies each year as I incorporate lessons garnered from evidence of student learning from the previous semester. Recently, in spring 2005, I decided to create my own course reader so that students could have models of how both academic and nonacademic writers combine personal approaches with the telling of history. Each section contained articles that took students on an intellectual journey from ├ČTheory: Framing Identities and Histories├« to ├ČPractice: Storytelling and History-making├« and finally to ├ČVisions: What Are You Going to Do to Make History?├« Articles included excerpts from Raymond Barrio├şs The Plum, Plum Pickers, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz├şs ├ČInvasion of the Americas and the Making of the Mestizocoyote Nation,├« and Paul Takagi├şs ├ČGrowing Up as a Japanese Boy in Sacramento County.├« 45 Learning the different ways historians portray the past is an important part of the scaffolding├│ instructional support├│students need to author their own history. They choose their own research topics, often from their lived experiences or out of a commitment to social justice or a desire to learn about struggles for equality ignored or minimized by their high school history textbooks. They are required to write an abbreviated research prospectus that describes the topic, takes a metacognitive look at initial assumptions, details research questions, and lists sources. They explore the campus library, online archives, and resources in surrounding communities. I encourage them to look at a range of possibilities for primary materials: published and unpublished sources such as newspapers and diaries; visual records found in photo albums and films; everyday artifacts including family cookbooks and clothing; evidence from the built environment seen at local cemeteries and in memorials; and aural sources encompassing oral histories as well as music. I involve my students in a cognitive apprenticeship by making visible and explicit to them my own thinking about the construction of historical narratives. I explain how I decide which sources to use, question evidence, and analyze findings.46 I work with students to unwrap the art of storytelling and the discipline of critical thinking while my education technology assistant demystifies how to create computer-generated short films. As they might in drafting an outline of a paper, but working with multiple layers of evidence, students juxtapose images, text, special effects, and sound in what video makers call a storyboard. Students also write a reflection on the reasoning behind their choices. As these storyboards change during the course of the semester, I collect evidence of how students are learning the iterative nature of historical knowledge as they undertake successive edits of their digital narratives, visually rearranging the elements on their storyboards. What follows are three short examples of how students grow into their roles as citizen historians, learning to place themselves in history, and to present their narratives to a wider public, including fellow students, their families, and communities. ├ČLook what I have found!├« declared one of my students, the daughter of farmhands who work in the fields surrounding California State University, Monterey Bay. Proudly, Marisa produced a picture of her grandfather marching with C├łsar Ch┬Ěvez, her little sister in his arms. After many hours of researching the United Farm Workers (UFW) movement at the local library, she had found the photograph buried in the newspaper archive. With this discovery, Marisa now felt confident that she could document her family├şs connection to making history. The subsequent revision in her research focus, from abstract to personal, informed her choice to create a bilingual, bicultural film, using both Spanish and English audio narration, Latino and Anglo visual representations, and music from both cultures. Her film presented the photo of her grandfather surrounded by the red and black colors of the United Farm Workers while other clips featured compelling images drawn from magazines, newspapers, and family photo albums. Marisa had succeeded in weaving her family├şs personal experiences into a broader social history├│one that made sense to her and to her community.

In 1970, when California vegetable growers refused to recognize the United Farm Workers (UFW) union, the workers went on strike, and their leader, César Chávez, called for a nationwide boycott of lettuce and in consequence was jailed. Cecilia O’Leary’s student Marisa Jimenez searched the local history room of the Steinbeck Library in Salinas, California, and found a December 1970 clipping of her grandfather Antonio Margarito supporting the boycott. She included it in a media presentation for O’Leary’s course Multicultural History in the New Media Classroom. Slide from “The Life of Antonio Margarito: The Bracero Program,” California State University, Monterey Bay, fall semester, 2002. Courtesy Marisa Jimenez. Another project, ├ČA Place to Remember,├« told the history of a nine-year battle in San Francisco to keep the International Hotel (I-Hotel), home to Filipino seniors, from being torn down. It opened with a full-screen image of an empty lot filled with weeds and remnants of a concrete foundation while Megan, the film├şs narrator, asked, ├ČWhat does an address mean? Whose lives and what histories lay behind the numbers?├« The film later cuts to images of thousands of protesters juxtaposed to scenes of Filipino elders being dragged out of the I-Hotel by deputy sheriffs. The audience hears Megan├şs voice reading an excerpt from an interview: ├ČIt filled my heart with anger, I hated how the city let something like this happen. If they were white it probably wouldn├şt have happened.├« Taken by surprise, the audience learns that those are the words of her father, Rey Mojica, ├Čone of the thousands of protesters there that morning.├« Part Filipina, the student producer had embarked on her research because she had wanted to find out more about her heritage. In her research Megan found out that her own father had been one of the protesters. That discovery enabled her to revise her understanding of her connection to the struggle and to place herself and her family within it. At the close of the semester, she planned to give copies of her film to the International Hotel Senior Housing Organization and to share it with her parents, hoping her project ├Čtouches my father as much as it has touched me.├« In a third project, Nicole chose to focus her digital history on an aspect of Italian culture in San Jose. Enthusiastic about the film she had created, she showed it to her large extended family. Everyone crowded around the television, taking great pride in seeing how Nicole├şs grandfather, a high school dropout, became a leading figure in bringing Italian accordion music to California├şs Bay Area. Images from scrapbooks, newspapers, wedding invitations, and community programs moved across the screen. At the end Nicole had included a clip of accordion music, but to her surprise, instead of applause, a heated debate erupted. The family demanded to know why she had used ├ČSicilian├« rather than ├ČItalian├« music to conclude her film. Until that moment, Nicole had not realized the two were significantly different. Her family├şs enthusiasm for making sure the evidence she used was right made the reciprocal nature of constructing historical knowledge possible and visible in her very own living room. Their heated response spurred her to want to revise her digital history and get it right├│although our class had already ended. Going public can involve risks, as in Nicole├şs case. But the public presentation of the digital history increases students├ş excitement about the relevance of the past as they see themselves as citizen historians imparting knowledge to others. After close readings of student evidence culled from over three semesters of collecting digital histories, student reflections, and videoed exit interviews, I am confident that my students leave my classes with the ability to contextualize themselves in history. They are aware of the reciprocal nature of constructing historical knowledge and the iterative process in which new evidence constantly reshapes ideas and interpretations. They can, in the words of one student, not only ├Čdialogue with books and communicate with primary sources from the past├« but also integrate words, sounds, and visuals in the public representation and narration of history.47 41 On the relationship between new-media pedagogy and elements of quality learning, see Randy Bass, ├ČEngines of Inquiry: Teaching, Technology, and Learner-Centered Approaches to Culture and History,├« in Engines of Inquiry, ed. Coventry, 3├▒26. 42 What students bring into the history classroom is a crucial area for future research on student learning. See Pace, ├ČAmateur in the Operating Room.├« On assets-based approaches to multicultural learning, see the special issue ├ČPedagogies for Social Change,├« ed. Susan Roberta Katz and Cecilia Elizabeth O├şLeary, Social Justice, 29 (Winter 2002), 1├▒197. 43 In approaching documents, students enact processes similar to those of historians. See Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts. 44 T. Mills Kelly, ├ČFor Better or Worse? The Marriage of the Web and the Classroom,├« Journal of Association for

History and Computing, 3 (Aug. 2000)

45 Raymond Barrio, The Plum, Plum Pickers (Binghamton, 1971), 84├▒94; Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, ├ČInvasion of the Americas and the Making of the Mestizocoyote Nation: Heritage of the Invasion,├« Social Justice, 20 (Spring├▒ Summer 1993), 52├▒55; Paul Takagi, ├ČGrowing Up as a Japanese Boy in Sacramento County,├« ibid., 26 (Summer 1999), 135├▒49. 46 On teaching strategies, see Bain, ├ČInto the Breach,├« 334├▒35. 47 Matthew Fox, ├ČStudent Reflection,├« Spring 2005, California State University, Monterey Bay, (in Cecilia O├şLeary├şs possession). Next essay: "Conclusion" > |