Teaching the Article

Exercise 2

Music, Sound, and Race

In the 1960s rock and blues enthusiasts debated whether a white boy could play the blues. Similar debates have popped up about white rappers in the world of hip-hop. (In the late 1980s the focus was on the Beastie Boys; a few years ago Eminem addressed the question in his film, 8 Mile.) Such debates--can a "white" person play "black" music?--echo similar debates from the early twentieth century. At that time, though, the question was usually inverted: Could a "black" person play "white" music?

By issuing all kinds of music by African Americans--not just blues, jazz, and popular music, but also art songs, arias, and religious music--Black Swan challenged deeply held beliefs that racial identity was innate and immutable, and that music expressed and reflected racial characteristics. According to the pseudoscience of the era, Africans and their descendants were biologically inferior to other humans, so their music must belong to a distinct, inferior class. In Black Swan's vision, high-quality recordings of black artists performing European-style music would turn this reasoning on its head.

This exercise, which looks at Black Swan's recordings and the emergence of the industry's race records category, prompts us to examine how race is understood in culture.

The Recordings of Black Swan

What ideas are brought to discussions of black music and of race in music? Why was Harry Pace dedicated to recording so many different kinds of music by African Americans, even though blues records paid Black Swan's bills?

First, listen to all or part of these Black Swan blues recordings from 1921-1923:

- Ethel Waters, "Down Home Blues" (1921)

- Trixie Smith, "My Man Rocks Me" (1922)

- Mary Straine, "Ain't Got Nothing Blues" (1922)

Please note: Listening to audio clips requires the free Quicktime player.

What characteristics do these recordings have in common? How do they differ? What themes (musical, lyrical) emerge? Based on these recordings, what generalizations might one make about the so-called vaudeville blues of the early 1920s? Is this somehow black music? If so, in what ways?

Now consider another set of recordings, also released by Black Swan from 1921-1923. Do definitions of black music hold up for these examples? Do they resemble the blues songs? If so, how? What impressions do these recordings create?

- Isabelle Washington, "I Want To" (1923)

- Four Harmony Kings, "Ain't It a Shame" (1921)

What happens when we consider examples of Black Swan records such as these:

- Florence Cole-Talbert, "The Bell Song," from the opera Lakmé (1922)

- Marianna Johnson, "The Rosary" (1921)

What might we make of the pairing on a single Black Swan record of an old Negro spiritual with a ballad inspired by a Sioux love song, arranged and performed in a formal (European) manner?

- C. Carroll Clark, "Nobody Knows De Trouble I've Seen" (1921)

- C. Carroll Clark, "By the Waters of Minnetonka" (1921)

What do you hear in the recordings? Are they black music? How do these Black Swan recordings from the early 1920s reinforce or challenge dominant ideas of black music? How do these songs and performances complicate the idea of racial categories in music?

Race Records

Black Swan's recording program should be seen in the context of the broader recording industry. As Black Swan's fortunes declined, other companies created a category of records, called "race records," aimed at Negro consumers. The industry tried to appeal to people whom it had earlier scorned, but it did so in a way that isolated them. While African Americans at the time often referred to themselves as "the race" (their leaders were known as "race leaders"), the marketing category that borrowed that language functioned in many respects "as a Jim Crow annex," in the words of a Black Swan ad.

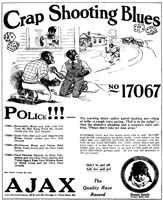

What factors and motivations might have led record companies to develop this distinct marketing line? How did its existence contribute to ideas about race (that is, racial difference)? Some advertising for race records was simple and unobjectionable, but some exploited racist caricatures. Two such ads discussed in the article--"Lonesome Mamma Blues" and "Crap Shooting Blues"--appeared on the entertainment page of the Chicago Defender, the nation's leading African American newspaper, where many unexceptionable advertisements were published (frequently alongside the others).

What issues are raised--about race, advertising, and the music business--by the following advertising materials:

|

"Emerson Race Records," advertisement, Emerson Records (1924) |

"Victor Records," catalog cover, Victor Talking Machine Co. (1929) |